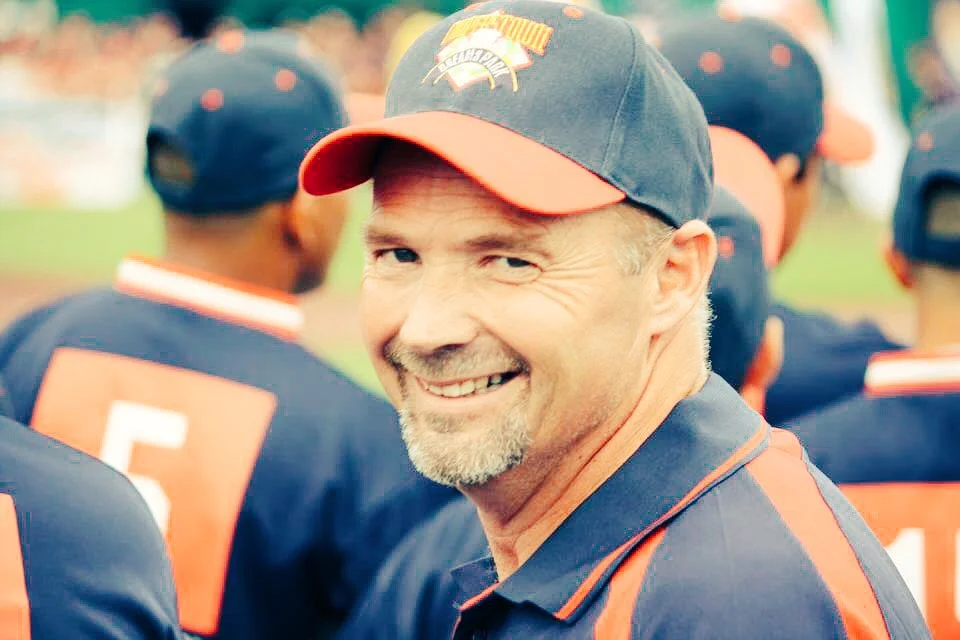

R. I. P. Troy Pennock

By C.J. Pentland

Canadian Baseball Network

The British Columbia baseball community lost one of its most dedicated, influential members on Oct. 17, 2016. Troy Pennock, a long-time coach, colleague, and friend of many, passed away at the unfair age of 53.

A coach in Richmond, North Langley, with various tournament teams, and most recently with the Langley Jr. Blaze, Pennock led by example. His dedication to baseball inspired both players and coaches, and enabled him to connect with everyone on a personal level.

“He wasn’t demanding, but he was hard working,” said Grant MacDougal, who first met Pennock in the 1990s through baseball in Whalley, and most recently coached with him in Langley. “He never took time off. If he was putting his time in, he wanted to be working and dedicated to that. He was a student of the game – he was always learning.”

Pennock played ball while growing up in New Westminster, and always had a love for baseball and football – which led him to coaching both sports. A father of three sons, he coached their teams in Whalley, North Langley, and then in Richmond in 2007. After his son Cody stopped playing he stepped away from coaching for a bit, but started to miss it. He got back in touch with Richmond coach Ryan Klenman, and then came out on a regular basis in 2012 – driving close to an hour from Langley to Richmond to join the team.

“He’s a fun-loving coach, absolutely loves the game,” said Klenman. “He could be a tough guy at times when needed, but he had the respect of everybody on the field. It was really hard not to like him. Any boys that played for him, once they talked to him it was almost like immediate respect.”

His positive impact stemmed from his ability to connect the fundamentals of the game with larger life lessons. In his role as an assistant coach, he would balance out the other coaches by being either the good cop or bad cop when needed – getting after a kid one moment, but then making him laugh shortly after. Many kids saw him as a father figure, with an outpouring of posts on social media reflecting his impact. “One of my favorite coaches I’ve had. Always brought a smile to the field and made practices all the better” tweeted Nick Brammer (@6brammer).

“We had some good games where we were down, and [I remember] staying cool and collected and talking to the kids and not screaming or yelling,” said MacDougal. “He could see kids getting down on themselves, and he was a motivator. He was the guy that would say ‘hey, you’re going to fail in this game, but it’s the next at-bat, or the next pitch that you’re going to throw, or the next ball that you’re going to get. Be mad, but don’t pout about it, because it’s going to come right back at you.’”

“He could be an a** one second, but five seconds later he’s got his arm around the kid and making him laugh, making him understand ‘I’m helping you become a man,’” said Klenman. “Coaches like that are rare; he totally stood out, and that’s why him and I always worked so well together.”

Klenman and Pennock coached together on several teams, heading to PNC tournaments in the US, the BC Summer Games, and to Arizona with the Diamondbacks Scout Team. Medical issues took their toll on Pennock in recent years – he suffered from diabetes, which led to the amputation of half his leg – but they didn’t do much to slow him down. One such moment of perseverance came in 2014, when the two coaches led the Zone 4 Team to the BC Summer Games in Nanaimo.

“Troy had diabetes, and he had a little cut on his toe, and it didn’t get better,” said Klenman. “And then all of a sudden it started turning different colours, and the docs had to amputate it to save his foot. It happened literally two weeks before the Summer Games, and he was hobbling around all weekend, in so much pain – the foot stunk like you wouldn’t believe – but you never would’ve thought by the look on his face that his bothered him.

“Whether he was sleeping on the hard floor of the classroom [where the team was lodged], not getting enough food, dealing with the heat, hobbling around on the ball field, it didn’t matter – when he was there, you could see the joy that he had. And just seeing him in that much pain – and obviously as the years have gone by I’ve seen him get worse and worse and worse with things, with him losing half of his leg now at the end – no matter with him, when you saw him on the field, he was in element, he was in his happy place. Nothing was going to hurt him when he was on the field.”

In the weeks before he passed away, Pennock continued to battle. A couple weeks before he was to head down to Arizona with the Diamondbacks Scout Team, he checked into the hospital with what he thought was the flu, but it turned out to be a mild heart attack. He stayed for a few nights, and despite being released two days before the departure day, he flew to Arizona. If he wasn’t on a no-fly list, he was making the trip.

“[Baseball] was his escape from his reality that body was slowly shutting down on him, and it didn’t matter. He’s there and nothing could bother him,” said Klenman, who coached the team with him.

“In Arizona, he was in rough shape – he had to get carted around on golf carts to get to the park. Even when he was on the field he would stand up before the game and feeling like garbage, couldn’t even lift the fungo bat. But right before the game, all of a sudden all of his energy would perk up, and he’d be able to give a speech to the boys; he’d be able to fire ‘em up, he’d be able to start cracking jokes to loosen the boys up when needed, and it was like ‘where the hell did all this energy come from?’. He’s always been able to do that, and it’s always blown me away.”

Upon returning from the trip, Pennock felt weak and his leg had ballooned in size. After going back to the hospital he suffered a fatal heart attack, something the doctors could’ve done nothing about. As Klenman said, he at least got to go on one last trip doing what he loved.

The Langley Blaze will be putting up a sign up on the wall out at their home field, McLeod Park, as a reminder to future generations of his influence to the community. Evidence of the positive impact on those he coached was made clear at his celebration of life on Nov. 12, when several current former players attended to honour his legacy.

Pennock dedicated thousands of hours to the BC baseball community, whether helping kids he’d known for years, or reaching out to new players to get more kids involved. Yet through it all, it was never about himself.

“I spent a lot of time with him, and I knew it was always about the kids,” said MacDougal. “It was about the game and the kids.”