Book Review: The Man Who Made Babe Ruth: Brother Matthias of St. Mary’s School

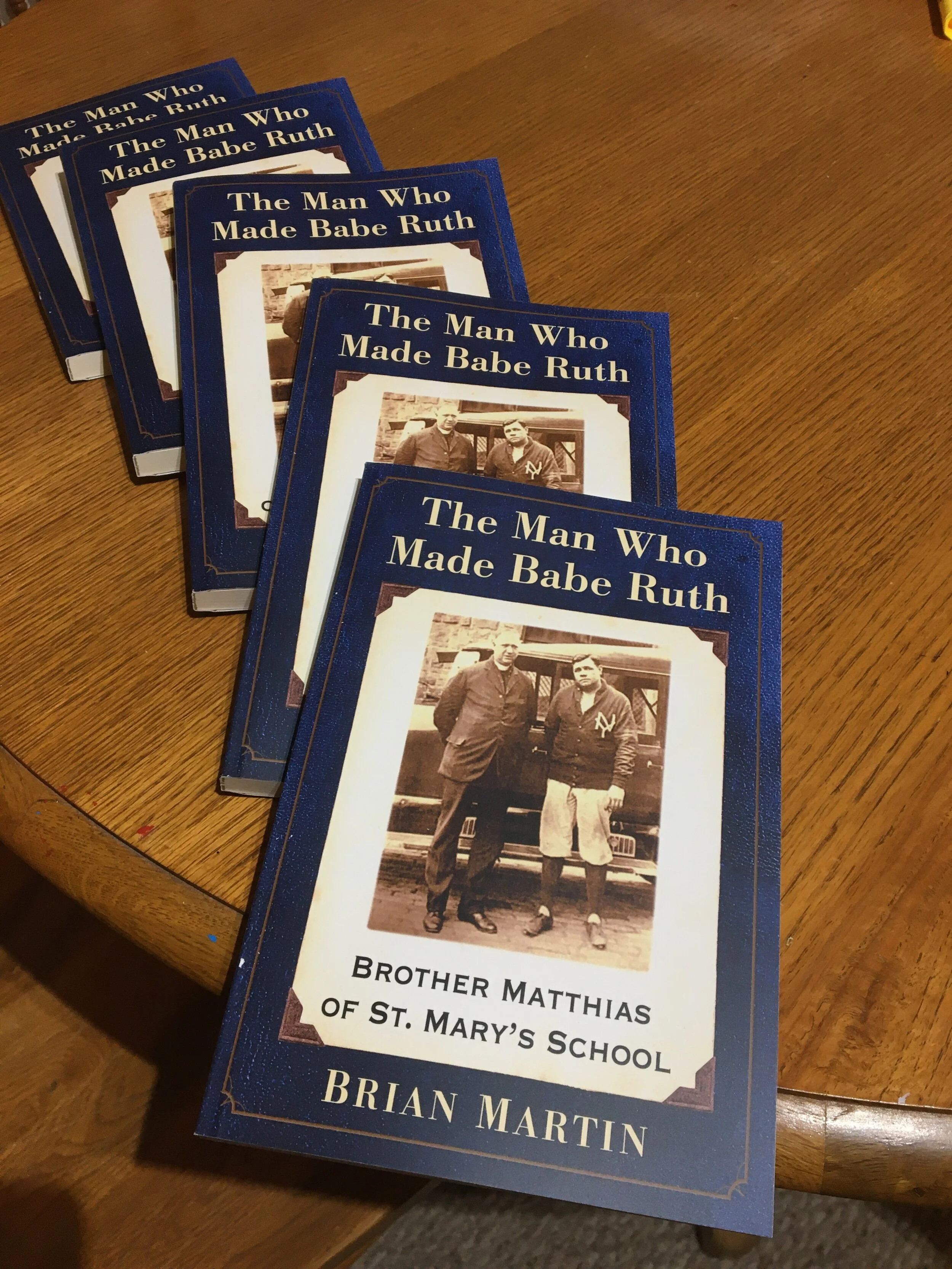

Book Review: The Man Who Made Babe Ruth: Brother Matthias of St. Mary’s School, by Brian “Chip” Martin

By Kevin Glew

A Canadian was the “greatest man” that Babe Ruth had ever known.

And it’s that unheralded Maritimer that the spotlight is finally shone on in Brian “Chip” Martin’s superb new book, The Man Who Made Babe Ruth: Brother Matthias of St. Mary’s School.

For far too long, Brother Matthias, who was raised in Lingan, N.S., has been relegated a bit part in The Bambino’s story and Martin’s riveting and meticulously researched book, at long last, remedies this.

In Martin’s page-turner, we learn that not only did the hulking 6-foot-6 prefect of discipline and director of all physical activity at St. Mary’s Industrial Training School in Baltimore help shape Ruth mentally – instilling in him much-needed values and beliefs – but he was also responsible for introducing The Babe to baseball and for influencing Ruth’s home run swing.

“Brother Matthias swung the bat with a powerful uppercut, despite the prevailing wisdom that a level swing was more likely to produce line drives and create trouble for infielders and outfielders alike,” writes Martin. “Ruth developed a long swing with an uppercut that launched balls a long distance . . . Brother Matthias’s approach to hitting was unorthodox but effective, Ruth copied it and went on to revolutionize the game.”

Often described a gentle giant, Brother Matthias was born in Nova Scotia in 1872. Raised in the Catholic faith, he moved with his family to Boston was he was eight. As a teen, he decided to pursue a religious calling and officially became an Xaverian Brother around the turn of the century. His impressive size, calm demeanour and innate sense of fairness made him ideal for the role of chief disciplinarian at the St. Mary’s Industrial Training School, which was an educational institution primarily for boys with behavioural issues who had been sent to them by the courts.

Brother Matthias also taught classes and served as a baseball coach, where the boys – including Ruth who arrived at St. Mary’s as a seven-year-old on June 13, 1902 – marvelled at his skills.

“Ruth spoke about seeing Brother Matthias stand at one end of the schoolyard with a mitt on his left hand and bat in his right, toss a ball up and belt it, sometimes more than 350 feet over the centerfield fence,” writes Martin.

This description of Brother Matthias’s skills is a small sample of the impressive details that Martin, a topnotch investigate reporter with The London Free Press for four decades, is able to share.

In his excellent book, Martin offers several reasons why Brother Matthias’s role in Ruth’s development has not received its proper due. The biggest reason was likely Brother Matthias’s shy nature. He didn’t like talking about himself or his influence on Ruth. In fact, Martin unearthed what’s believed to be the sole interview – and resulting 1935 article written by Thomas Shehan of the Boston Evening Transcript – that Brother Matthias granted to the press in which he spoke about Ruth.

Another reason for Brother Matthias’s lack of recognition is that Brother Gilbert, a more self-promoting colleague from nearby Mount St. Joseph College, generally accepted praise for Ruth’s development even though his role in it was minimal. A popular banquet speaker, Brother Gilbert seemed to talk and write about Ruth at every opportunity. The reality was, as Martin notes, the only part Brother Gilbert played in Ruth’s baseball career was recommending the youngster to his friend Jack Dunn who owned the International League’s Baltimore Orioles.

One of the biggest strengths of this book is the vivid picture Martin is able to paint of Brother Matthias through his descriptions, which is a testament to the author’s tenacity, research acumen and topnotch writing skills.

“Brother Matthias was an imposing figure at six-foot-six with blue eyes and fair hair, rather sloping shoulders and a pear-shaped yet muscular body of more than 250 pounds barely disguised by his cassock,” writes Martin, adding that the mere presence of the big Cape Bretoner could quickly quell any commotion among the boys at St. Mary’s.

It’s hard to pinpoint exactly when Matthias and Ruth met. Ruth first arrived at St. Mary’s on June 13, 1902 as a wild, unprincipled and – his parents would contend – incorrigible seven-year-old. Ruth’s father, also named George, and his mother, Katie – both of whom had issues of their own that are identified in the book – were attempting to run a saloon and they sent their son to St. Mary’s because, among other transgressions, he was skipping school, stealing fruit and chewing tobacco.

Thanks largely to the guidance of Brother Matthias, Ruth grew to enjoy his time at St. Mary’s and his social skills improved. With the big Canadian as his father figure, counsellor and mentor, Ruth was quick to make friends and had a magic touch with the younger boys at the institution who looked up to him. Brother Matthias taught him to care for others and about the importance of forgiveness.

“He always built me,” Ruth would say of Brother Matthias’s influence.

Baseball was the most popular sport at St. Mary’s and Brother Matthias also devoted extra time to Ruth to help improve his skills. Ruth spent a lot of time as a left-handed throwing catcher for an intramural squad until one day Brother Matthias spotted Ruth laughing at his own pitcher who was being hit hard by his opponents. Disgusted at Ruth’s behaviour, Brother Matthias sent Ruth, who had never pitched before, to the mound as punishment. The move turned out to be fortuitous. Ruth would dominate and it was his pitching prowess that would earn him his first professional contract.

Martin writes that the story of how Ruth was eventually signed by Dunn has varied over the years. But it’s generally agreed that Brother Gilbert was the one who recommended the then 18-year-old Ruth to Dunn, who gave him a $600 salary to join the Baltimore Orioles for the 1914 season.

Ruth was apprehensive about leaving St. Mary’s, but, as Martin unearthed, Brother Matthias, as usual, was there to provide encouragement.

“You’ll make it, George,” Brother Matthias said.

After a successful start to Ruth’s pro career with the Orioles, a financially strapped Dunn sold Ruth to Quebec-born Boston Red Sox owner J.J. Lannin in July. Ruth’s first season in the American League was a frustrating one. He pitched little and was going stir crazy on the bench when he was sent down to the International League’s Providence Grays. Martin writes that the sole letter of support that Ruth received that year was from Brother Matthias.

“You’re doing fine, George. I’m proud of you,” Brother Matthias reportedly wrote.

Ruth was so touched by the letter that he kept it for the rest of his life.

That note would help inspire Ruth to superstardom, first as a pitcher with the Red Sox and then as a history-making slugger with the New York Yankees. And through it all, Martin notes, the Sultan of Swat never forgot St. Mary’s or Brother Matthias.

In his grandest show of appreciation, Ruth bought Brother Matthias not one, but two Cadillacs. Martin writes that the second was purchased after the first was demolished by a train after Brother Matthias got it stuck on a railway track during a rainstorm.

“I’d have bought him one [a Cadillac] every week if he hadn’t put a stop to it,” Ruth said.

Martin also shares that even well into the Ruth’s big league career that when the Yankees felt their slugger was spiralling out of control away from the field they would summon Brother Matthias to come and counsel their star.

Also, to Martin’s credit, this book is not a hagiography. Brother Matthias was not perfect. The author shares details of an inappropriate relationship that a 59-year-old Brother Matthias allegedly carried on with a 23-year-old woman in the early 1930s. It was this behaviour that eventually got him relocated from St. Mary’s to the St. John’s Preparatory School in Danver, Mass.

Brother Matthias lived his final years in Massachusetts before he died in 1944. But even in his later years, he continued to speak glowingly of Ruth.

“There was never a better boy at St. Mary’s School in Baltimore than George,” said Brother Matthias in the aforementioned article in the Boston Evening Transcript in 1935.

And the admiration was mutual.

“It was at St. Mary’s that I met and learned to love the greatest man I’ve ever known. His name was Matthias – Brother Matthias of the Xaverian order . . . I saw some real he-men in my 22 years in organized baseball and in the years since my retirement in 1935. But I never saw one who equalled Brother Matthias,” wrote Ruth in passage in his 1948 autobiography that Martin shares in the book.

And until now the story of the “greatest man” Ruth had ever known had never been told so masterfully and in such fascinating detail. This is another outstanding effort by Martin, who’s already one of Canada’s top baseball writers and historians.

You can purchase a copy of the book here or via the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame in St. Marys, Ont.