Brash becomes Kingston's first big leaguer

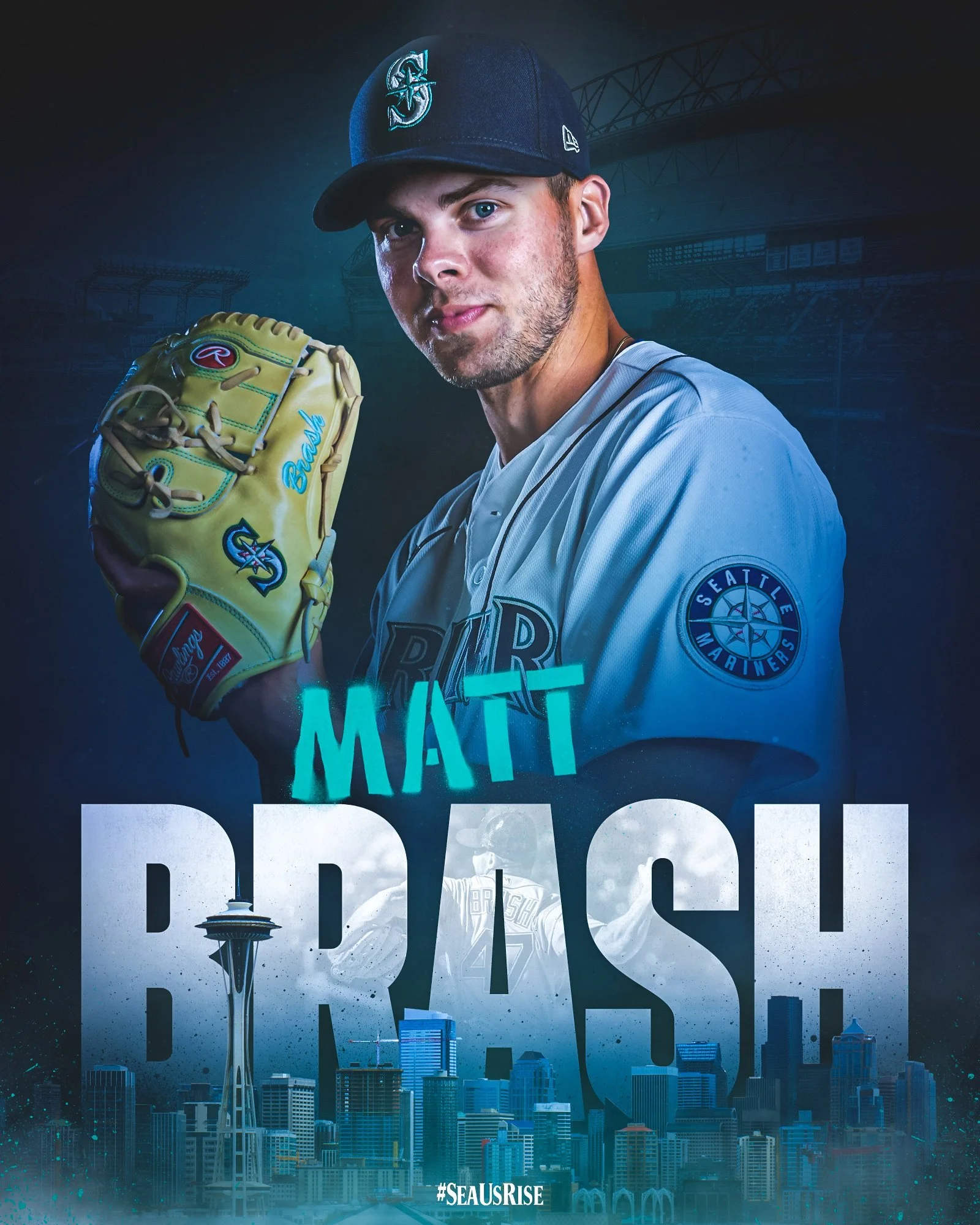

Kingston Thunder alum Matt Brash (Kingston, Ont.) made his first major league start on Tuesday. Photo: Seattle Mariners/Twitter

April 16, 2022

By Patrick Kennedy

Canadian Baseball Network

Hours after he’d made Kingston baseball history in a packed ballyard in Chicago, some 1,100 kilometres southwest of here, pitcher Matt Brash summed up his first-ever Major League Baseball start with unwavering optimism.

Never mind that he now sports a big-league career win-loss mark of 0-1. His attitude is no surprise. Brash brims with confidence, always has. Unwavering belief in his own ability has been integral in his ascent to “The Show,” and self-confidence will be paramount if he is to remain in baseball’s Xanadu. So, while his Seattle Mariners dropped a 3-2 decision to the host Chicago White Sox, the M’s touted talented rookie effectively erased any minute traces of self-doubt.

“I felt really comfortable out there,” Brash said over the phone from Harry Caray’s Italian Steakhouse, where he dined post-game with family and friends. “I felt like I belonged in the big leagues.”

If his debut is any indication, he’s right about that.

Pitching before a capacity crowd in the White Sox home opener, Brash tossed 5 1/3 innings with six strikeouts, one walk and four hits, one of which was game star Luis Robert‘s solo home run in the sixth inning. That bomb snapped a 1-1 deadlock.

“That’s on me,” the right-hander confessed on the 408-foot tater. “(Robert) was sitting off-speed all day. I should’ve thrown a fastball.” (Robert also swiped two bases and saved two runs with a third-inning terrific catch at the centre-field wall.)

All in all, it was a splendid first day on the job for the 23-year-old Bayridge Secondary School grad, who enticed 11 swings and misses on his curveball, the most in an MLB debut in a dozen years. And with his first pitch at the Windy City’s charmingly named “Guaranteed Rate Field,” Brash became the Limestone City’s first-ever major-league ballplayer, fulfilling the dreams of thousands of youngsters through the years dating back to Kingston’s earliest reported ballgame in 1872. It’s only taken 150 years, but we finally have our first big-leaguer.

“Isn’t it just wonderful,” remarked 88-year-old baseball diehard Art Leeman, himself a stellar pitcher in his day and one of only a handful of local ballplayers to play professionally, none of whom ever reached the double-A level. “It’s just such an amazing achievement for this young man, one of our own, to make the major leagues, because it’s quite a climb to get there.”

Brash’s hometown tipped its ball cap in recognition of the long-awaited accomplishment. City council proclaimed April 12 Matt Brash Day. At the Brass Pub on Princess Street, local hardball fans gathered to watch “Brash at the Brass,” while at the pitcher’s old high school, BSS teacher Geoff Stewart, Matt’s high school baseball coach, hosted a “watch party” for staff, students, alumni and anyone else who was keen on seeing history in the making.

Brash’s big-league unveiling was also big news on the campus of Niagara University, his college alma mater in Lewiston, N.Y.

“This is as big as it gets down here,” Rob McCoy, longtime coach of the Division 1 Purple Eagles baseball club, noted. “It’s a huge, truly monumental event for our school.”

“We’ve had 16 past students go on and play in the major leagues, but Matt’s our first modern-day big-leaguer,” McCoy pointed out in a phone interview the other day.

Indeed, a quick search reveals the first 14 players on that list all played prior to 1925, and briefly at that. The 15th big-leaguer to come out of the private Catholic university was an outlier — baseball legend Sal “The Barber” Maglie, so nicknamed for his intimidating inclination to “shave” plate-crowding batters with his fastball.

Maglie pitched in 303 games and compiled an enviable 119-63 career win-loss mark that included 93 complete games. The most recent Niagara alumnus to reach baseball’s big time was pitcher Edward “Rinty” Monahan. That was in 1953, nearly 70 years ago. Rinty, too, was not overworked. His career total for manager Connie Mack’s lowly Philadelphia A’s: 10 2/3 innings. Since then, no one, that is until Matthew Aurel Brash toed the rubber in Chicago last Tuesday.

Now that he’s reached the mountaintop, we look back at Brash’s climb to his profession’s elite level. We also look at just how he managed to arrive there in such a short span of time.

For starters, outside of having what’s known in the sport as a “live arm,” Brash possesses four key intangibles: dedication, desire, perseverance and the aforementioned confidence, each one above-average grade. And of course, this being baseball, a game in which Lady Luck is an everyday player, he’s had the good fortune to avoid injury.

Those closest to him in baseball recognized Brash as a special talent almost from the get-go.

Randy Casford, who coached and mentored teenager Brash with the Kingston Thunder, called him “a perfectionist who takes pride in mastering the art of pitching.” Casford, whose own family sat next to the Brash clan 30 rows behind home plate in Chicago, made that comment seven years ago after Brash had showcased his burgeoning talent in an all-Ontario midget A quarter-final tilt.

“He has a golden arm,” Casford lauded at the time, a compliment he has often repeated since then.

Brash’s astounding ascent to the major leagues no doubt surprised the scouts of the San Diego Padres, the team that selected him in the fourth round of the 2019 MLB draft then dealt him to the Mariners as the proverbial throw-in “player to be named later” to complete a trade at the end of the COVID-cancelled 2020 minor-league season. Some throw-in.

Unlike the Padres, Niagara coach McCoy, however, was not startled by the pitcher’s rapid success.

“We kind of knew we had something special after Matt’s very first start for us,” McCoy said, recounting a five-inning, three-hit, seven-strikeout outing versus Norfolk Sate. “He was a freshman, but he went through those guys like a hot knife through butter.”

In his sophomore year, Brash had difficulty “navigating the workload,” McCoy recalled. “His body, his musculature, they couldn’t handle the violence and efficiency of his delivery.”

Brash made good use of the pandemic shutdown. He added muscle and mass and conditioned his body to withstand the rigours of life as a professional pitcher.

The result? Brash blossomed in 2021, and from afar the Mariners took notice. He fanned 142 batters in just 97 1/3 innings between High-A and double-A and posted an ERA of 2.31 between those two levels and a 1.14 WHIP. He was named the organization’s minor league pitcher of the year. Seattle added him to its major-league roster last September, and though he officially carded six days of MLB service time, he did not pitch during the ball club’s frantic, but failed, stretch drive.

In three appearances (two starts) during this spring’s training camp, Brash worked 9 1/3 innings with 12 strikeouts, two walks and just a single earned run (0.96 ERA). Seattle manager Scott Servais reckoned the rookie not only had earned a spot in the rotation but he was arguably the team’s best pitcher in camp.

Another reason for Brash’s meteoric rise has been the development and deployment of a wipe-out slider, a devastating “out” pitch that complements his high-90s fastball. The slider, his signature pitch, is considered “off the charts” by the analytics crowd. In a recent pre-season game at a facility that had Statcast tracking, Brash threw 10 sliders that averaged 2,865 rpm, including one that spun at a mind-bending 3,158 rpm. The major league average in 2021 was 2,417 rpm.

Brash picked up the slider from a Niagara teammate early in his junior year, the season in which he demolished the school’s single-season strikeout record.

“Yeah, I taught him the pitch,” former Purple Eagles pitcher Tyler Howard chuckled, “but Matt throws it a hundred times better than I ever did.”

Now a policeman in Niagara Falls, N.Y., Howard and his dad drove eight hours to take in Matt’s big-league debut.

Ironically, it was a slider that Luis Robert deposited in the right-centre bleachers to ruin Matt’s coming out party in Illinois. The young pitcher learned, first-hand, how big-league hitters deal with belt-high pitches that linger over the middle of the plate.

Last December, this observer ended a column on Brash with an opinion on the latter’s impending status as Kingston’s first major-league player, breathlessly writing: “It’s only a matter of time now.”

That time has come. Now we await and hope for an ever-brighter future.

Patrick Kennedy is a retired Whig-Standard reporter whose knuckleball still flutters. He can be reached at pjckennedy35@gmail.com.