Canada welcomed former Negro Leagues players

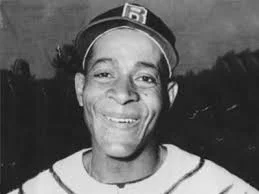

Longtime scout Ed Heather called former Negro Leagues star Wilmer Fields (above) the greatest Intercounty Baseball League player he ever saw. Fields was a three-time IBL MVP (1951, 1954-55) with the Brantford Red Sox.

By J.P. Antonacci

Canadian Baseball Network

Jackie Robinson taking the field as a member of the Brooklyn Dodgers marked a watershed moment in North American professional sports. But with its brightest stars soon scooped up by previously whites-only major league teams, the Negro Leagues began to falter, closing up shop for good 13 years after Robinson’s big league debut in 1947.

The integration of Major League Baseball was “certainly the death knell of the Negro Leagues,” says Bob Kendrick, president of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City. However, he added, the end of segregated baseball also sent an influx of talent north to Canada.

“When (major league) baseball started siphoning the talent away from the Negro Leagues, a lot of the older players came up to Canada to resume their playing career,” Kendrick said during a Pitch Talks event in Toronto earlier this month.

Kendrick knows of Canadians who played in the Negro Leagues, but more common were Negro League players who were too old to be of interest to major league teams finding a new professional home north of the border.

“The culture and climate was so different here (in Canada), where they were more readily accepted than they were at home in the United States,” Kendrick said.

As a youngster in Galt (now Cambridge, Ont.) in the 1950s, Galt Terriers fan Ed Heather cheered on the roughly two dozen former Negro League players who joined the independent Intercounty Baseball League (IBL).

“Most of them were pretty darn good players, but in those days, unfortunately, even if they were as good as the white guys, they had to be better. There were a number of players who would’ve been in the big leagues if not for their colour,” said Heather, who went on to cover southwestern Ontario as a scout for the Toronto Blue Jays.

The Terriers team for which young Ed chased batting practice home run balls featured Gentry “Jeep” Jessup, who had pitched for the Chicago American Giants in the Negro Leagues and dominated on the mound and at the plate in Galt.

Outfielder Bob Thurman played for the Intercounty Baseball League's Brantford Red Sox in 1953 before being signed by the Cincinnati Reds.

Jessup was one of a group of African-American IBL players that included Ed Steele, who once patrolled the outfield alongside Willie Mays with the Birmingham Black Barons, and former Homestead Grays outfielder Bob Thurman, who joined the Brantford Red Sox in 1953 before being signed by the Cincinnati Reds.

“Within two years he was in the big leagues,” Heather said.

The Negro League players quickly became the stars of their new teams.

“These guys who came up were the prominent players in the league,” Heather said, calling Wilmer Fields, a pitcher/outfielder from the Homestead Grays, “the best player I’ve ever seen in the Intercounty, period.”

The American imports were also fan favourites.

“(The fans) loved them,” Heather said, citing Jessup as a prime example. “I swear to God he could’ve run for mayor. He was so popular. Everybody loved him.”

Jimmy Wilkes helped the Intercounty Baseball League's Brantford Red Sox win five straight championships.

Jimmy Wilkes, a speedy outfielder who hit leadoff for the 1946 Negro League champion Newark Eagles, helped Brantford win five straight IBL titles during his decade with the club. The Philadelphia native settled in Brantford after his playing days, working for the city and serving as a highly respected Intercounty umpire for 23 years.

The IBL was just one Canadian destination for Negro League players who saw their livelihood threatened in the United States. Stars such as Ray Dandridge, Leon Day and Willie Wells played alongside former big leaguers, Latino standouts and local amateurs in the Manitoba-Dakota League (better known as the Mandak League), which fielded teams like the Winnipeg Buffaloes, Dauphin Red Birds and Saskatoon Gems. Manitoba’s Barry Swanton, author of The Mandak League: Haven for Former Negro League Ballplayers, 1950-1957, estimates that 140 former Negro League players suited up in the Mandak League during its brief existence.

Black players were also welcomed on rosters in the International League (in which Jackie Robinson made his debut with the Montreal Royals before being called up by Brooklyn) and the semipro Quebec Provincial League, a league of choice for black and Indigenous ballplayers since the 1930s.

“Canada has had a long connection to black baseball, with a lot of guys coming north to play and barnstorm in all parts of Canada,” Kendrick said.

Canadian visitors to the Negro Leagues museum – Kendrick says there are many, especially when the Blue Jays are in town to play the Royals – will appreciate one of the museum’s Canadian connections. Rocker Geddy Lee, a noted baseball fan often seen in the seats behind home plate at Rogers Centre, was so impressed by his first tour of the museum that when he later spotted 200 baseballs signed by Negro League players up for auction, he bought them for the museum.

Geddy Lee, lead singer and bassist for the Canadian rock band Rush, donated his collection of baseballs signed by Negro Leagues players to the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City.

The Rush bassist later donated another 200 autographed Negro League baseballs and was on hand to dedicate the display of what is now one of the largest collections of its kind in the world.

“Can’t say I was much of a Rush fan before, but I’m a big Rush fan now,” Kendrick laughed.