Prankster, ex-MLBer Comstock has fond memories of Alberta

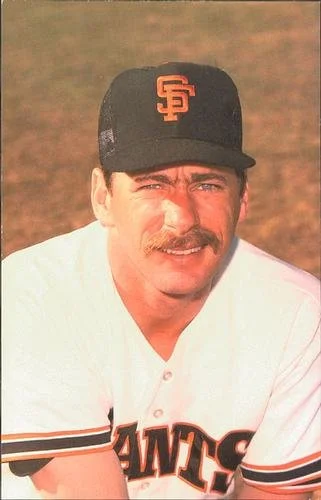

Keith Comstock. Photo: Wikipedia

*This article was originally published on the Alberta Dugout Stories website on December 23, 2021. You can read it here.

December 24, 2021

By Ian Wilson

Alberta Dugout Stories

They’re the type of tales that are best accompanied by a frosty, golden-hued beverage.

Ideally, they are enjoyed while perched atop a barstool in a room lit dimly enough that you can properly observe the storyteller’s eyes, but you cannot thoroughly inspect the cleanliness of the floors. Preserved in your mind at a hole-in-the-wall bar that has the perfect acoustics for murmurs and belly laughs.

These are the stories that former Major League Baseball (MLB) pitcher Keith Comstock shares. They are pranks, oddities and, “Did that really happen?” moments. They include remembrances of loss; analysis of pain, both real and simulated; and eyewitness accounts that twist the ears of baseball fans.

The travels of his professional playing career are bookended by stops in Alberta, but his life in baseball goes on, so pull up a chair and grab a cold one. You’ll want to hear all about it.

———————————————————————————————————————

Listen to Alberta Dugout Stories interview Keith Comstock here.

———————————————————————————————————————-

A quick disclaimer, however, and one with apologies to Han Solo. In this game of true-and-false with Alberta Dugout Stories, it’s all true … all of it.

The left-handed hurler first made his way to Canada in the summer of 1975 after he completed his freshman year at Canada College in his home state of California.

“Guys who had good years in college were often asked to go certain places like Colorado and get a chance to go up to Alaska,” recalled Comstock.

“Players had an opportunity to go to Canada as well, and Red Deer was one of the ones that had contacted my college with an opportunity to go up there and pitch during the summer and the opportunity also to go up and pitch against older guys … being a junior college guy, if you got the opportunity to go there you jumped at it, which is what I did.”

The Red Deer Generals of the Alberta Major Baseball League (AMBL) saved a spot in the rotation for the import and hooked him up with a couple of easy-going summer jobs.

“I remember they got me a job pumping gas and also in charge of turning on and turning off automatic water sprinklers. I got paid to do that,” said Comstock.

“So actually, I went there and said, ‘Okay, what time do they need to get turned on?’ The guy went: ‘They’re automated. You don’t have to turn them on.’ And I go, ‘Okay, what time do I have to turn them off?’ He said: ‘They’re automated, they turn off by themselves.'”

In early June, Comstock got his first and only start for the Generals against another future MLB pitcher, Ernie Camacho, and the Calgary Jimmies. Neither pitcher excelled in the error-filled contest, which saw the Jimmies prevail 12-8 in front of 300 Cowtown fans. Even worse for Comstock, who pitched into the seventh inning, was a shoulder injury that ended his season.

“I separated my shoulder and I told them, ‘I’ll be two weeks.’ They said, ‘Nope, we’ve got to find somebody else.’ I was shipped out of there in three days. If you got hurt, you didn’t stick around – you needed a pitching staff, you couldn’t wait for somebody to get healthy,” Comstock told Alberta Dugout Stories: The Podcast.

The injury denied Comstock the opportunity to square off against another legendary talent. Knuckleballer Jim Bouton drew big crowds across Alberta when he suited up for the Jimmies in July.

It didn’t take long, however, for Comstock to return to Wild Rose Country.

FATHERLY ADVICE

He was drafted in the fifth round by the California Angels in the 1976 MLB Amateur Entry Draft and his first professional posting was with the Idaho Falls of the Pioneer League, a circuit that made stops in Lethbridge on a regular basis.

Armed with some words of wisdom from his father, Comstock set out on the start of his pro career.

“I’ll never forget the advice he gave me when I wanted to go for baseball. With how competitive baseball was, he said, ‘You just make sure that you put all your eggs in this basket, then, because if you have something to fall back on, you’ll fall back.’ So, that’s what I did. I put all my eggs in baseball,” he said.

It should have been the most exhilarating time in Comstock’s life, and in many ways it was, but it was also bittersweet because his dad, Herb, had been diagnosed with cancer.

“It was really difficult for me because he was going through the worst part of his life and I was going through the best part of mine. It was tough to find some kind of middle ground for me,” remembered Comstock.

Between the chalk lines, he was performing well. Idaho Falls used him as both a starter and a reliever, and despite a 1-4 record, he recorded five saves and 45 Ks in 37 innings. Comstock surrendered just one long ball and put up a 3.89 earned run average (ERA).

Comstock’s parents were making arrangements to come watch their son pitch that summer, but a game at Henderson Stadium in Lethbridge altered their plans. Comstock got the start in late July against the Expos and was mowing down batters through the first five frames. He struck out six batters and gave up four hits and no runs in that time, but when he went out for the sixth inning, hitter Chris Wood lined a single off the pitcher’s ankle that sent him to the hospital for X-rays.

“He had quite a lump on his ankle when he got to the dugout,” noted Reno Lizzi, the Lethbridge Expos president, in the Lethbridge Herald.

The injury sidelined Comstock for most of August, but more importantly it meant his father never got the opportunity to watch him play as a professional. Herb passed away later that year, shortly before Keith’s 21st birthday.

“That was a difficult time, as well, not just for me, but for us all. He never had a chance to see me pitch as a pro … so there were some really, really tough times,” said Comstock, who graduated from rookie-level ball to Single-A in 1977.

“At that time, when you get something good happen, you call up your mom or you call up your dad, so you lose that connection. You’re not talking to your dad anymore.”

Depression set in. That would eventually give way to motivation, but not until years later when he was cut loose by the Angels.

“Some of the things that (my dad) had said to me, I started to remember … then it became more of a motivation after I got released that first time,” said the San Francisco born southpaw.

ORIGINAL PRANKSTER

Some of his depression also seemed to find an outlet in more humorous situations. And, as much as he was honing his skills for a major-league mound, Comstock was also developing some big-league ability as a practical joker.

On a road trip to Wausau, Wisconsin while he was with Quad Cities, Comstock got into some mischief by stealing the team bus and running over a fire hydrant. The prank landed him in jail.

“Yeah, you read that right. Back in the seventies you could do a lot of things without, you know, there was no internet, there was no YouTube. I would’ve been a YouTube sensation back in those days,” laughed Comstock.

“But there was nothing I could get released on because I was throwing really well and my manager just came down and, back in those days they just fined you, took you out of jail and that was it. If I was doing really crappy, I probably would’ve got released. At that time I was his closer, so I didn’t get released.”

Comstock kept grinding in the minors. He kept all his eggs in that baseball basket.

He joined the Oakland Athletics organization in the early 1980s and made his way up to Triple-A, but no further.

In 1983, he gained notoriety for his part in an unusual trade. The A’s sent him to the Detroit Tigers for $100 and a bag of baseballs, which he had to deliver. As Comstock explains, they weren’t just any baseballs and the delivery aspect was no big deal.

Charlie Finley, the owner of the Athletics, tried to get MLB to use fluorescent orange baseballs for night games in the 1970s. It was an interesting, if not cockamamie, experiment that was quickly rejected. The baseballs, however, lingered and found occasional use during batting practice. They also became collector’s items.

When it came time to finalize the trade, someone in Detroit’s management coveted the keepsakes and asked for them to be included in the transaction.

“When I got sold, which was not uncommon, there were various ways for you to move to different organizations. In today’s environment we do it for just one dollar now, but back in the day they’d give one hundred dollars. So, it was one hundred dollars and they asked me to deliver these orange baseballs,” said Comstock.

“It wasn’t like I was upset with it or anything like that. There were a dozen baseballs, I threw them in my bag … there was no offence, none intended. It was more of a gesture from one friend to another. At that time I was appreciative of Oakland. They could’ve easily released me but they sold me to the Tigers and the Tigers needed an older guy at Double-A and, believe it or not, ’83 was a big year for me, it kind of turned my career around. If I don’t get sold, things might not have happened.”

Comstock played well for the Birmingham Barons in 1983, going 12-3 with a 3.21 ERA, four complete games and 136 strikeouts through 145 2/3 innings.

From there, he signed as a free agent with the Minnesota Twins and after years of minor-league service he finally made his MLB debut, at the age of 28, on April 3, 1984.

MY OH MY

Despite finally cracking a big-league roster and experiencing success at Triple-A, Comstock decided to pitch in Japan in the mid-80s. Signing with Tokyo’s Yomiuri Giants was primarily a financial decision but it also put him in the dugout with a baseball legend.

“The minor leagues put you into debt, you know? So, I had a chance to go to Japan and make some money and get out of that minor-league debt. That was really attractive to me and my family,” said Comstock.

The Giants were managed by Japanese Baseball Hall of Famer Sadaharu Oh, who holds the world career home run record with 868 dingers. The first baseman was named the Nippon Professional Baseball (NPB) most valuable player in the Central League nine times and he claimed Japan’s Triple Crown twice.

“Obviously, getting a chance to meet Sadaharu Oh was a great privilege. I really got to see how he went about his work,” said Comstock, who recalled one night at the hotel when Oh signed autographs for several hours until well past midnight.

“That’s just kind of the guy he was. I remember some of the advice he gave me. I’ll never forget that, he said, ‘Shoot for the moon. If you miss, you’re among the stars.'”

Striving for moonshots didn’t always work out, however.

On one occasion, Oh asked Comstock to do his best imitation of a statue during a plate appearance.

“Granted, I didn’t have a great batting average at that time, but I went up there with the bases loaded and nobody out and right before I walked up to the plate, he comes up and says, ‘I have a very bad feeling about this and I wish for you not to swing at anything. Just take the out,'” remembered Comstock, who intended to follow his manager’s counsel.

“I went up to the plate and the very first pitch was this ball right down the middle, and instinct took over and I hit it to the shortstop for an easy 6-4-3 double play. He wouldn’t talk to me for two weeks.”

There were other lessons from the Land of the Rising Sun.

“Japan did a lot of things for me. It helped me deal with umpiring, which was really bad, and I figured when I came back to the big leagues it was going to be really bad as a rookie. It taught me also to pitch in front of crowds and the lights, which was different and just to be around the media and stuff. All that stuff played a big part of me when I came back from Japan, just being a little bit more mature in those areas really helped me out,” said Comstock, who spent two seasons with Yomiuri.

A GIANT LEAP

When he returned to the United States, he needed to find work again. He cold-called a few teams, including the Los Angeles Dodgers and his hometown San Francisco Giants, to let them know he was available. Al Rosen, the president and general manager of the Giants, saw him pitch a no-hitter in a Golden Gate Park league game and inked him the next day.

“It was pretty cool because all my family were big Giants fans … my father, my dentist, everybody. It was a great experience to sign with them,” said Comstock.

He made 15 relief appearances for San Francisco in 1987 and the experience allowed his friends and family to see him pitch in The Show for the first time.

“My dad had passed, obviously by that time, so my mom she never saw me pitch in the big leagues before, so that was pretty cool,” he said.

“The first pitch I threw, Andres Galarraga fouled it off and it landed in my brother’s hands.”

Suiting up for San Fran also gave Comstock the chance to see the only non-mound action of his MLB playing career. The Giants were on the road in Atlanta and manager Roger Craig initiated a bold strategy that put Comstock in unfamiliar territory. Craig had watched Comstock shag fly balls in the outfield during batting practice and was impressed with what he saw.

“He said, ‘I’ve seen you shag, you’ll be OK.’ – I took shagging really, really serious back in the day. He put me in right field and brought in (another pitcher) to pitch to Dale Murphy, with Ken Griffey Sr. on deck,” Comstock told Alberta Dugout Stories.

“I remember just going out to right field and I remember thinking to myself, ‘Wow, this thing is really far away.’ That’s the first thing I thought, ‘Man, I give up balls this far away.’ When you’re shagging during batting practice, you’ve got all sorts of people around, you’ve got people shagging, you’ve got the press and that, just tonnes of people. Then, during a game I was just thinking it was me and the centre fielder and the left fielder, it was just so much territory.”

The first pitch sent a foul ball down the right field line that put Comstock in motion.

“I went and chased it down the right field line – this was old Atlanta Fulton County Stadium – and in that right field line is just a bullpen with a wall that goes just up to your thigh. I remember hitting that almost full blast. It almost flipped me over into the bullpen. And in the bullpen my hat came off and they wouldn’t give me my hat back. I was fighting with their bullpen, they’re throwing their dip at me and everything they could throw at me, they’re throwing water.”

When he finally got his ball cap back, he returned to right field and the next pitch was blasted over his head.

“It obviously is a home run, thirteen, fourteen rows up,” said Comstock.

“And then I just kind of ran into the wall, not so much scaling it, just ran into it. I almost knocked myself out, I ran into it so hard.”

Following that adventure, Craig sent Comstock to the bump to face Griffey Sr., who smacked a triple.

“That was not the funnest experience,” said Comstock.

GROIN CONCERN

Another year meant another team for the well-traveled lefty.

Comstock pitched for the San Diego Padres and their Triple-A affiliate, the Las Vegas Stars, in the late 1980s. It was this Pacific Coast League (PCL) sojourn that made Comstock a celebrity.

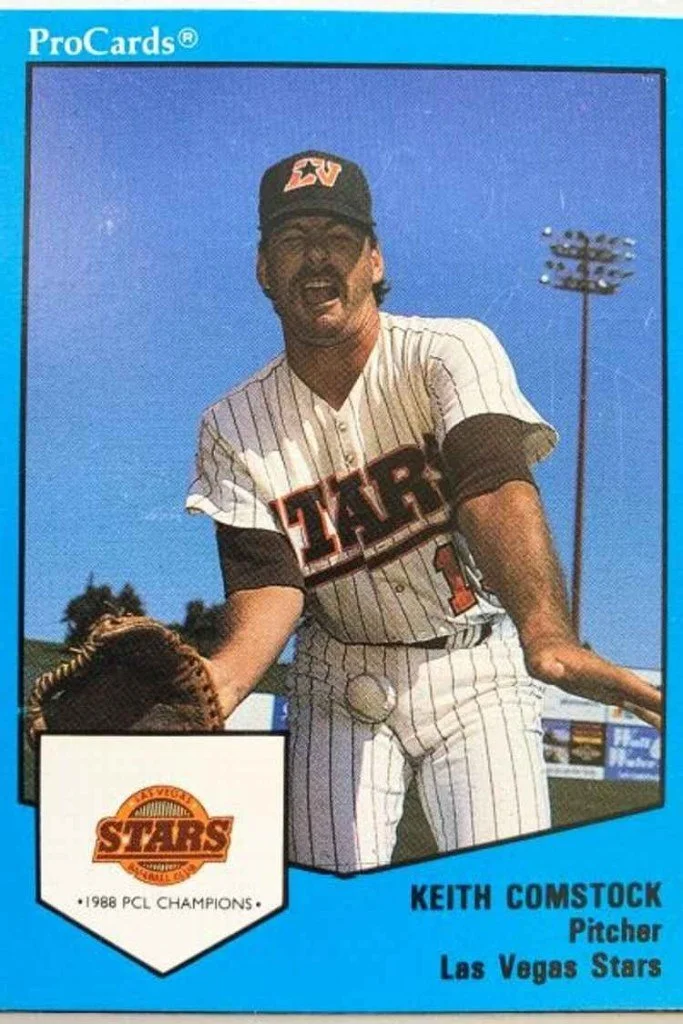

More specifically, it was a baseball card from his time with the Stars that entered him into baseball folklore.

Keith Comstock’s most famous baseball card.

Comstock had appeared on baseball cards before, from the ugliest designed, poorly photographed cardboard collectibles of the minors to the beautifully composed and sharp looking cards that make major leaguers look good. He’d been around long enough to see some uninspired images grace the hobby and he wanted to inject some life into things.

“It was just mundane. You’d do the same card and the same thing over and over again, same kind of stretch position or whatever the case may be. There were a lot of guys in the big leagues who had done some baseball cards that had some swear words on it, you know Billy Ripken’s famous baseball card, so Topps was very leery the next year of guys doing weird baseball cards. A pitcher couldn’t be holding a bat, a position player couldn’t be doing a windup, you know? They were really strict on these things now,” said Comstock.

“But I just had this wild hair up my butt to do this picture of a comebacker where the ball hit my nuts. I had to have it and I had to get it done.”

In this instance, it wasn’t Topps or one of the larger baseball card manufacturers that was tasked with getting Comstock to pose for a picture. It was a photographer hired by ProCards, a company that produced minor-league sets, that was in charge of capturing straight-laced Las Vegas players for the 1989 blue-bordered edition of the cards. The Stars, who won the PCL championship in 1988, had a stacked roster that included both Sandy and Roberto Alomar.

After his baseball-to-the-crotch idea was rejected by the photographer, Comstock persevered. Realizing each player had to sign a deal that allowed ProCards to use their image, and that several budding prospects had not been photographed yet, the veteran went to the clubhouse and urged his teammates to withhold their likenesses until Comstock’s silly request was granted.

“I had a lot of leverage going on with those guys not coming down and me being the elder statesman, me being the older guy … they could care less if they could come down and take a minor-league baseball picture. So, I had that leverage against that photographer. He was on time, he kept looking at his watch. He finally said, ‘OK, OK.’ So I got to take that picture,” laughed Comstock.

That picture became a collectible masterpiece that is considered the “funniest baseball card ever made.”

When Comstock first laid eyes on it, he knew he had achieved something great.

“I was so proud of that card,” he said.

“I remember looking at that card, taking it home and showing my wife and her looking at it, going, ‘Why are you making that face?’ I said: ‘You can’t see the ball hitting my nuts, are you kidding me?! This is the proudest moment of my baseball life!’ …. Thirty years later, when I’m getting notoriety from this baseball card, I finally went back to her and said, ‘See, I told you.'”

Over the years, he’s been asked about the card countless times and fans have even recreated it and sent him pictures of the resulting goofy images.

“Again, very proud moment in my life – everybody needs a legacy,” said Comstock.

Fun fact: Calgary is mentioned on the back of the card because Comstock pitched briefly for the Cannons in 1989.

MARINER MOUNDSMAN

Comstock joined the last MLB organization he pitched for, and it was a club that saw him at his most productive.

Between 1989 and 1991, he came out of the bullpen in 92 games for the Seattle Mariners and posted impressive numbers. Comstock went 8-6 with a pair of saves, a 3.07 ERA and 72 Ks in 82 innings.

“I was putting up some really good numbers because I had so many people who were working behind me. As a reliever you’re only as good as the people behind you. When I was a reliever with the Mariners, there were so many good arms behind me. It was just a pleasure to be with that talent, especially Randy (Johnson) and some of those young guns they had,” observed Comstock.

He also got to witness the emergence of Hall of Famers Edgar Martinez and Ken Griffey Jr.

One particular memory of Griffey Jr. stood out.

“One of my favourite stories of him was, he was in a really bad hitting slump and he had struck out and I was coming out to pitch. I remember it was the Brewers, but as they were running off the field to come to hit, Junior was going out to his position and said, “Don’t hit it anywhere near me because if I’m not hitting, nobody’s hitting.’ I just remember as a young 19-year-old kid being able to say that, I was really impressed by him. The best part was, if he ever got hit, you had to watch out because Randy was going to hit two of their guys. You hit Junior and we’ll hit two of you guys,” said Comstock.

In his final season of playing professional baseball, 1991, Comstock also made his way back to where it all began. He served as a reliever in 15 games for the Calgary Cannons during a rehab assignment.

“The good thing about being sent down to Triple-A at that time, man that was a really good team. You get to play with some future superstars like Tino Martinez and Richie Amaral and some of those guys. It was so much fun to be down there,” he said.

“But the best thing about being down in Calgary for me, as an older guy, was being able to watch some of those younger guys and I would never tell them about the cannon.”

The cannon in this case wasn’t the name of the team or the throwing ability of an outfielder. It was the militaristic prop that boomed loudly after every Calgary home run at Foothills Stadium.

“That was my favourite thing to watch those young kids after a home run, the cannon going off, oh my God, the opposing team, the young pitchers. It was comical. That was the big thing. I used to tell everybody, ‘Don’t say anything about the cannon.’ That was the cardinal rule. Some young kid came up, especially a young right fielder, that was right next to that cannon, cardinal rule, don’t say anything about the cannon.”

Comstock also remembered Foothills Stadium being a scary place to pitch because the high altitude made it a homer happy ballpark.

“Calgary used to put some pitchers right into the psychiatrist’s office, too. You’d come out of there, pitching an inning and a third giving up sixteen runs, you’d go holy shit, my career is over,” he said, adding the players dubbed one high-scoring series “the Calgary stampede.”

Comstock’s shoulder was in rough shape by this point, prompting him to rely on cortisone shots to get through that last season. But he was also thinking ahead and still heeding his dad’s advice about keeping his eggs in one basket.

“That year in Calgary, or even a couple years before that, I let coaches in other organizations know that I’d be into coaching when my playing days were done,” said Comstock.

COACH COMSTOCK

The minor-league journey started all over again when Comstock retired as a player. Between 1994 and 2005, he took roles at the rookie, Single-A and Double-A levels as a pitching coach and a manager. In 2006, the Los Angeles Angels made him their roving minor league pitching instructor and a short time later he joined the Texas Rangers, where he currently works as the rehab pitching coordinator.

“I knew I was sacrificing time away from my family. My wife knew that baseball was in my blood, so she was all for that at that time. But then there just came a certain time where I didn’t want to be a big league coach and I knew that and I wanted to settle down and be more of a coach that was around my family, so that’s where the Rangers came in. I told them I don’t want to travel,” said the grandfather who now lives in Arizona.

“I just wanted to settle in, so we came up with this job that was really one of the early creations of being a rehab pitching coordinator. They just found a need and had a lot of guys in rehab, we don’t know what to do with them, let’s create this job. That’s how it started.”

When he reflects on the sport that has given him so much, Comstock looks back with gratitude.

“I was always so thankful that the game slowed down for me to jump on and the game slowed down for me to jump off. It was like a ferris wheel and I know guys that would just stay in the game too long and the next thing you know, the game threw them out, instead of you being able to walk out. Being able to walk out graciously, even as a coach, I’m so thankful for that because I look at the guys who got thrown out of the game, no matter how good they were, they got thrown out and they can’t get back in,” said Comstock.

Baseball has definitely delivered enough comebackers to the crotch to make you wince. It’s always better if you can have a good laugh about it after.