From Stratford sandlots to Jarry Park, Landreth reflects on baseball career

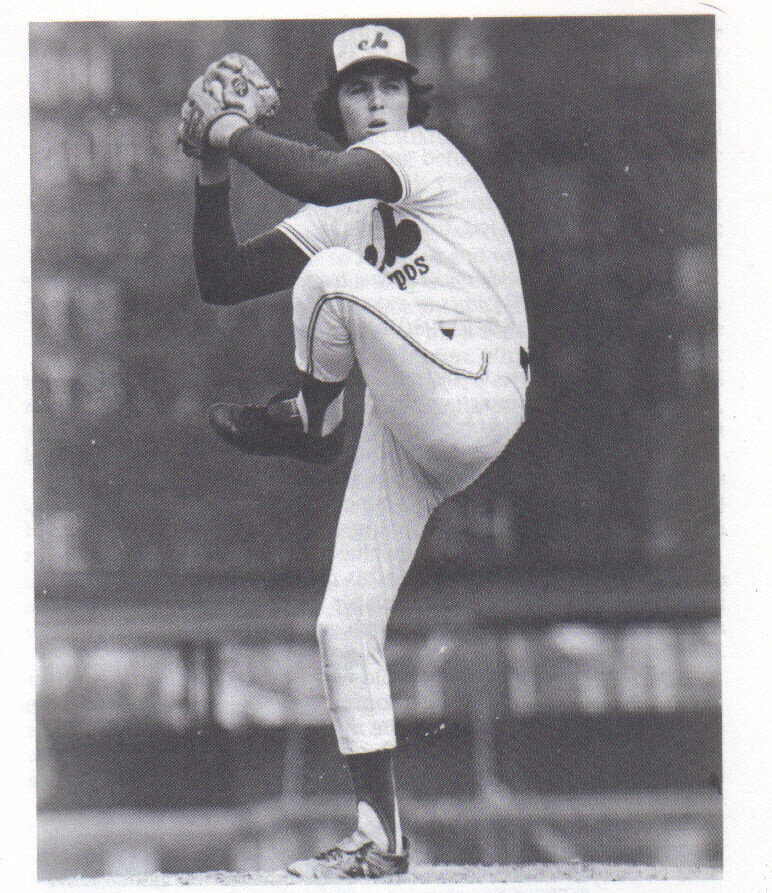

Larry Landreth (Stratford, Ont.) was the first Canadian that came up through the Montreal Expos system to play for the big league club. Photo: Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame/Montreal Expos collection

October 26, 2020

By Kevin Glew

Canadian Baseball Network

In the first inning of his major league debut, a nervous 21-year-old Larry Landreth peered in for the sign from his catcher Gary Carter.

Glowering back at him from the batter’s box was reigning National League batting champion Bill Madlock – an intimidating right-handed hitter nicknamed “Mad Dog.”

It was September 16, 1976 and the young Canadian right-hander, who had honed his skills in the sandlots of Stratford, Ont., was toeing the rubber for the Montreal Expos against the Chicago Cubs at Jarry Park.

His catcher (Carter) and left fielder (Andre Dawson) were future Hall of Famers and the man he was facing would eventually win four batting titles. He definitely wasn’t in Stratford anymore.

As he battled his first game jitters, Landreth could take some comfort in the fact that his parents, Don and Florence, were among the 2,877 in the crowd cheering him on in this Thursday afternoon contest.

Landreth was feeling pressure that day. Though becoming the first Canadian to be signed and developed by the Expos to play in the big leagues for the club was a tremendous accomplishment, it was also a burden. With it came more scrutiny and a seemingly endless stream of interview requests. It was a lot to absorb for a 21-year-old who just wanted to pitch.

Jerry Tabb, the first Cubs batter Landreth faced, had singled, but the Canuck rookie rebounded to strike out Joe Wallis. But now he had to contend with Madlock, who had batted a league-best .354 in 1975.

Landreth had studied Madlock’s swing the day before and noticed it was short. He figured his best strategy was to throw sliders in on the batting champ’s hands.

And the strategy worked.

On an 0-1 pitch, Madlock topped a ball to Expos shortstop Tim Foli who flipped it to second baseman Wayne Garrett who relayed it to first baseman Mike Jorgensen for an inning-ending double play.

Landreth would retire Madlock two more times, on fly balls to centre field, in the contest.

“I just kind of found what I thought was a weakness,” recalled Landreth, now 65, in a recent phone interview, when asked about facing Madlock that day. “And I went in there [with my slider] all the time.”

There would be a few more hurdles for Landreth in his first big league start, including overcoming his three walks in the second inning.

“The ball was moving all over the place,” recalled Landreth. “I remember Larry Parrish coming over to me and saying, ‘Look, kid, Just throw!’ He said, ‘Your ball is moving everywhere. Make that work.’”

That wisdom helped Landreth settle in and he got out of the second inning without allowing a run. In fact, he hurled six scoreless innings before Expos manager Charlie Fox removed him from the game.

“I’m still mad at Fox for pulling me,” said Landreth, only half joking, more than four decades later.

Sure, Landreth had walked six in the game, but the Cubs were not hitting him hard and he had only thrown 88 pitches. But as a rookie, Landreth wasn’t prepared to argue that vehemently with Fox and he left with the Expos leading 1-0. He eventually picked up the win in what turned out to be a 4-3 nail-biter.

Landreth shared his 1978 Topps rookie card with three other pitching prospects.

Looking back now, his debut couldn’t have gone much better for a young Canadian who had dreamed of pitching in the big leagues.

Born in Stratford, Ont., in 1955, Landreth cites his older brother, Doug, as his biggest baseball influence.

“We grew up in a time that it was just pick-up ball,” said Landreth. “And you just went to the schoolyard and you played Wiffle ball or whatever you could.”

Landreth was fortunate to grow up in Stratford where they had one of the best minor baseball organizations in the province. A star pitcher/shortstop as a kid, Landreth was a key member of at least four youth teams that won Ontario championships.

Reflecting on those days, Landreth, who once toed the rubber in front of the notoriously vicious Philadelphia Phillies fans at Veterans Stadium, says some of the most venomous spectators he ever encountered were those from Mahony Park in Hamilton. His Stratford teams regularly met Mahony Park in the provincial finals.

“They became our rivals,” recalled Landreth. “I can remember one game when I was in bantam or midget and one of the Mahony fans spit through the screen at me.”

Landreth attended some baseball camps as a teen, but there were no elite programs and he honed his skills primarily in Stratford minor ball.

“I just picked up pointers here and there,” he said.

His golden arm began attracting the attention of scouts in his early teens.

“I had phone calls all the way through bantam, through midget and then junior was the year that the scouts showed up a lot,” recalled Landreth.

And the Expos weren’t the only team interested in him. He was contacted by scouts from the Philadelphia Phillies, San Francisco Giants and Baltimore Orioles among others.

But the Expos made the most concerted effort to sign him. In October 1972, they brought him and his family to Montreal where they wine and dined him and he had the opportunity to watch Bill Stoneman throw a no-hitter at Jarry Park.

“I signed with the Expos basically because I was Canadian and they were Canadian,” said Landreth, who didn’t have an agent at the time.

Almost immediately after he signed with the Expos, the Orioles contacted him.

“I had just signed in Montreal when Baltimore called me. I had just signed on the dotted line,” he said. “In retrospect, I wish I would’ve went to Baltimore because I think they brought you up slower, and they weren’t expecting you to stand on your head when you go out on the mound . . . With Montreal, it was, ‘You’re here. You’ve got to do it!'”

Landreth officially signed with the Expos in March 1973 and was assigned to the club’s class-A Short-Season affiliate in Jamestown, managed by the fiery Walt Hriniak.

“He was a pit bull,” recalled Landreth of Hriniak. “He was 5-8 at the most, but he’d fight you in a heartbeat. He just didn’t accept failure.”

But Landreth liked the fact that he always knew where he stood with Hriniak. And Landreth not only impressed his manager on the mound (6-4, 4.01 ERA in 14 games), but also at the plate. Landreth went 11-for-34 (.324) that season.

“Hriniak would put a lot of hit and runs on when I was up,” recalled Landreth. “He would say, ‘I know you can hit it to the right side and I would just take an outside pitch and hit it to the right side.'”

Landreth’s breakout campaign in the Expos’ organization came the following year when he was promoted to their class-A club in West Palm Beach. That season, he went 15-7 with a 2.56 ERA in 26 starts and struck out 146 batters in 188 innings. He also threw 12 complete games, something a team would never allow a 19-year-old prospect to do today.

“My mindset when I pitched was to go nine innings,” said Landreth. “I argued with my managers. They’d come out the mound and I’d go, ‘I’m not leaving.’”

Photo: Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame

Landreth’s bulldog mentality and outstanding 1974 numbers earned him an invite to big league camp the following spring. At 19, he was the youngest player in camp and he would impress the Expos brass prior to being assigned to their double-A affiliate in Quebec City, where he recorded a 2.69 ERA in 25 starts and tossed a whopping 17 complete games.

Landreth had 13 wins for the triple-A Denver Bears in 1976.

This earned him a promotion to triple-A Denver in 1976. Despite having to deal with the thin air in Colorado, Landreth emerged as one of the club’s top starters, notching 13 wins for a team that also featured future Expos greats Dawson, Ellis Valentine and Warren Cromartie. Fellow Canuck Bill Atkinson (Chatham, Ont.) also pitched for that squad.

For his efforts, Landreth was one of the Expos’ September call-ups and, as noted earlier, he made his first major league start on September 16.

Carter was Landreth’s primary catcher in the big leagues and the Canuck righty enjoyed working with him.

“Carter was good to throw to,” he recalled. “You could shake him off and he might talk to you in the dugout. But a lot of times I didn’t shake him off because he knew the hitters better than I did.”

Landreth also marvelled at the talents of Dawson, whom he came through the Expos’ system with.

“I’ve never seen anyone with quicker hands in my life,” Landreth said of Dawson. “He’d be fooled on a pitch and still hit a rope.”

After the win in his debut, Landreth made two more starts for the Expos in 1976 and four appearances with them in 1977, but he spent the majority of that season in Denver, where he posted a 10-10 record and a 4.15 ERA in 29 starts.

After beginning the 1978 campaign in Denver again, he was dealt to the Los Angeles Dodgers for veteran reliever Mike Garman on May 20, 1978. Landreth didn’t feel good about the trade. The Dodgers were overflowing with pitching talent and he was worried he might get buried in their system. It also didn’t help that he was sent to the club’s triple-A Pacific Coast League affiliate in Albuquerque, where it was hard to keep fly balls in the park.

“There was a trough in Albuquerque that ran from right-centre to left-centre and if a fly ball got in the trough, you could kiss it goodbye,” he said. “I remember one game our centre fielder Joe Simpson came in to catch a fly ball it got in the trough and it travelled out of the park.”

Following a rough season in Albuquerque and not seeing a way back to the big leagues with the Dodgers, Landreth asked for his release and in the spring of 1979, he re-upped with the Expos.

Back with triple-A Denver in 1979, Landreth found himself growing disillusioned after being shuffled between the starting rotation and the bullpen, so at the age of 24, he decided to walk away from the pro ranks.

Landreth headed home and joined his brother, Doug, on the Intercounty Baseball League’s Stratford Hillers and helped them win a championship in 1980.

Shortly after that, Landreth became a fireman and would serve in that capacity for over 33 years until he retired in 2015.

Today, Landreth lives happily in Stratford, with his wife, Jane. The couple has three children, Sean, Kate and Scott, and three grandsons.

Landreth (middle) gets to catch up with his former Montreal Expos teammates Steve Rogers (right) and Bill Atkinson (Chatham, Ont.) each year at the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame induction golf tournament in St. Marys, Ont. Photo: Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame.

He spends a lot of time on the golf course, including participating in the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame’s fundraising tournament each year.

“Looking back I feel proud of the fact I developed my skills in a small city surrounded by people who had a love for the game and were encouraging and supportive,” said Landreth.