Glew: Remembering Doby's connection with Montreal on what would be his 100th birthday

Larry Doby had a special connection with the Montreal Expos and city of Montreal.

*The courageous and trailblazing Larry Doby, who became the first African-American player to compete in the American League when he debuted with Cleveland on July 5, 1947, would’ve turned 100 today.

He passed away in 2003.

I wanted to take time today to pay tribute to him, and also remember his special connection with the Montreal Expos and city of Montreal.*

December 13, 2023

By Kevin Glew

Canadian Baseball Network

It was the fall of 1975 and it seemed like the stage might be set for Larry Doby to once again make major league history.

Doby, who, in July 1947, became the first African-American player to compete in the American League, was a highly respected hitting instructor in the Montreal Expos’ organization and had made it known that he wanted to become the first Black major league manager.

He had almost broken the managerial colour barrier the previous season when he was working as Cleveland’s hitting instructor and the club struggled out of the gate, putting manager Ken Aspromonte on the hot seat. Doby was considered the favourite to take over. But thanks largely to his work with the hitters, the team snapped out of its slump and Aspromonte was spared, at least temporarily.

However, following the 1974 season, Cleveland did fire Aspromonte, but to Doby’s chagrin, the club hired Frank Robinson to be their player/manager, making him the first Black manager in major league history.

“I was bitterly disappointed,” Doby told the Montreal Gazette in April 1976 about Cleveland’s decision to hire Robinson. “My pride was hurt. It was the biggest disappointment of my life.”

Doby, who had been a trailblazing star with Cleveland in the 1940s and 1950s, felt a loyalty to the organization, but he had only taken the job in Cleveland with the encouragement of Expos president John McHale, who believed that with Gene Mauch entrenched as his manager, Doby had a better shot at managing in Cleveland.

“I never would’ve left Montreal in the first place if I didn’t believe I had a good chance to become the manager with the Indians,” said Doby in April 1976. “That is something I want to get across to the people of Montreal. I didn’t even want to leave the Expos.”

With Robinson as Cleveland’s new manager, Doby found himself unemployed after the 1974 season and in April 1975, he returned to the Expos as a roving minor league hitting instructor.

But when Mauch was fired following the 1975 campaign, Doby’s name came up as a potential replacement.

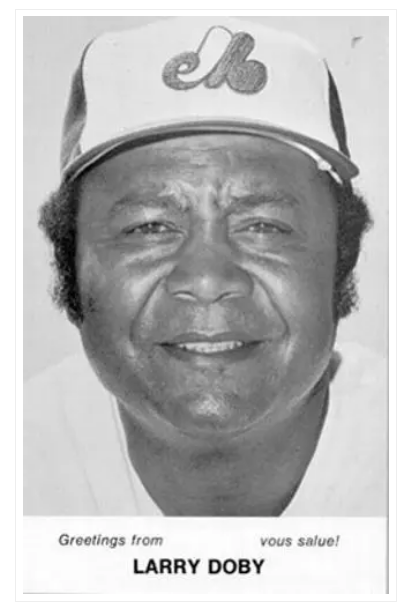

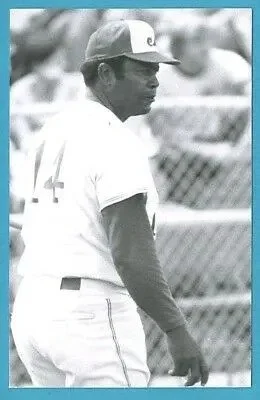

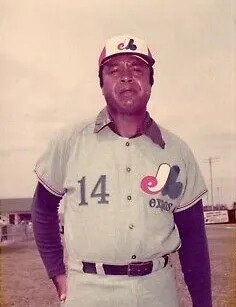

Larry Doby as a coach with the Expos.

Doby may have worked in the minors in 1975, but he had been the club’s big league hitting coach from 1971 to 1973 and had developed a strong bond with Expos players like Andre Dawson and Ellis Valentine.

But it wasn’t to be yet again for Doby.

The Expos hired Karl Kuehl, who had managed in the club’s upper minor league ranks for four seasons, to replace Mauch. Kuehl then hired Doby to be his big league hitting coach.

Under Kuehl, the Expos’ 1976 season was a disaster. The club lost 107 games and saw attendance drop to 646,704 — by far the lowest in franchise history. And with the club set to move from Jarry Park into the much larger Olympic Stadium in 1977, this was a huge concern.

The club had fired Kuehl in early September and replaced him with Charlie Fox on an interim basis. And the Expos, again, had the opportunity to hire Doby, but the club felt like they needed a manager with a proven track record, one that could help revive their increasingly indifferent fan base. So this time, Doby was passed over in favour of two-time World Series-winning manager Dick Williams.

With Williams in charge, Doby departed to take a job as batting instructor/first base coach with the Chicago White Sox. And after the Sox struggled in the first half of 1978, Doby did get his wish when he was hired to replace Bob Lemon as the team’s manager on June 30. He would lead the Sox to 37-50 record down the stretch in his only big league managerial gig.

It’s too bad, however, that Doby wasn’t given the opportunity to break the managerial colour barrier in Montreal. The city is rich in baseball history and, as you probably know, after the Brooklyn Dodgers’ signed Jackie Robinson, they assigned him to the triple-A Montreal Royals in 1946 to ease him into integrated baseball in a city with a reputation for racial tolerance.

Robinson and his, wife, Rachel, fell in love with Montreal and its people, and at the end of the season, he didn’t want to leave. “This is the city for me,” he said. “This is paradise.”

Doby felt the same way about the city.

“Please let everyone in Montreal know that I feel just like I’m leaving home,” Doby asked Montreal Gazette reporter Ian MacDonald to share in December 1973 after he left the Expos to take the job in Cleveland.

Doby and his family had settled into an apartment on St. Marc Street.

“The move is tough on my children,” Doby said to MacDonald about leaving Montreal for Cleveland. “They love Montreal. My wife (Helyn) loves Montreal but at least she knows Cleveland too, so it won’t be as tough for her.”

I wasn’t aware of the depth of Doby’s emotional connection to Montreal until I began doing research for this blog entry. I knew Doby had been a coach for the club, but I didn’t realize he was one of the team’s original scouts and was one of the most influential hitting coaches in Expos’ history.

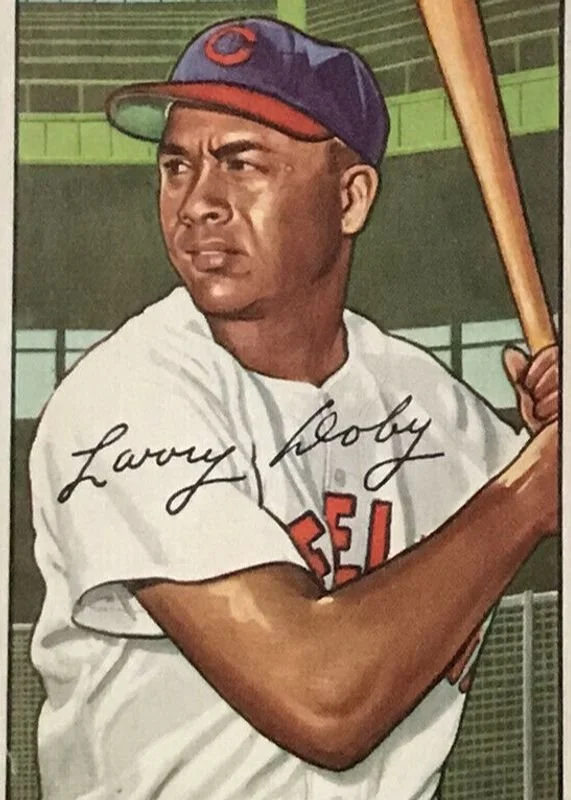

Larry Doby’s 1952 Bowman baseball card.

Like most of you, when I think of Doby, I think of him as the first African-American player in the American League. Born in 1923, he spent much of his early life in New Jersey before joining the Newark Eagles of the Negro National League.

Unlike Robinson, who played a year of professional integrated baseball with the Montreal Royals before breaking MLB’s modern colour barrier in 1947, Doby went straight from the Negro Leagues to Cleveland’s major league club. When he first walked into the Cleveland clubhouse, many of the players wouldn’t even shake his hand.

Doby made his major league debut just three months after Robinson, on July 5, 1947. He batted .156 in 29 games that year, but he excelled the next year, batting .301 with 14 home runs for Cleveland’s last World Series-winning squad. From there, he developed into an elite slugger, leading the American League with 32 home runs in 1952 and 1954. In the latter campaign, the 6-foot-1, 180-pound outfielder also topped the circuit with 126 RBIs and helped propel Cleveland to 111 wins and an American League pennant.

In all, in a 13-season major league career, which also included stops with the White Sox and Detroit Tigers, the seven-time All-Star finished with a .283 batting average and 253 home runs.

But following his playing career, he had difficulty getting a job in professional baseball.

“I tried hard to get something in baseball for eight years, but there was nothing,” Doby told the Montreal Gazette in an article published on September 28, 1973. “I knew there were openings, but there were none for me. My only hope came from John McHale. When I got in touch with him, he was with the commissioner’s office, he told me that if he ever took over a club again he’d get in touch with me – and sure enough when he came to the Expos in 1968 he did.”

Doby was one of the first scouts hired by the Expos and one of his initial duties was evaluating players on the Philadelphia Phillies before the 1968 National League expansion draft. McHale and Expos general manager Jim Fanning must have liked when they heard from Doby because the club took three Phillies – Gary Sutherland, Mike Wegener and Larry Jackson – in the draft.

Larry Doby was involved with the Expos before they even played their first game.

When Expos spring training began in West Palm Beach, Fla., in 1969, Doby was there, providing hitting instruction to the club’s top prospects. A number of the team’s most notable early players – including Mack Jones, John Boccabella and John Bateman – worked extensively with him.

“I owe any career that I have remaining in baseball to Mr. Doby,” Boccabella told the Montreal Gazette in February 1971.

During the 1969 season, Doby served as a scout and a roving minor league hitting instructor. He tutored players in Rookie Ball, class-A West Palm Beach and in Instructional League. The next year, he was promoted to the position of organizational batting instructor and special assignment representative.

“He showed us last year that he has outstanding ability to teach young hitters,” Fanning told the Montreal Gazette in February 1970.

The plan was for Doby to make stops with the team’s affiliates throughout the season. His work was so widely praised by the players and fellow coaches that Doby was promoted to be the Expos’ major league hitting coach in 1971.

“I’ve never known more than two people who could teach hitting and communicate with players and Doby is one of them,” said Fanning to the Montreal Gazette after Doby was promoted. “I could hire 10 pitching coaches in the next hour, but I could sit here for a month and not find one good batting instructor. Doby has the rare qualities . . . the record, the authority, the patience, the ability to communicate.”

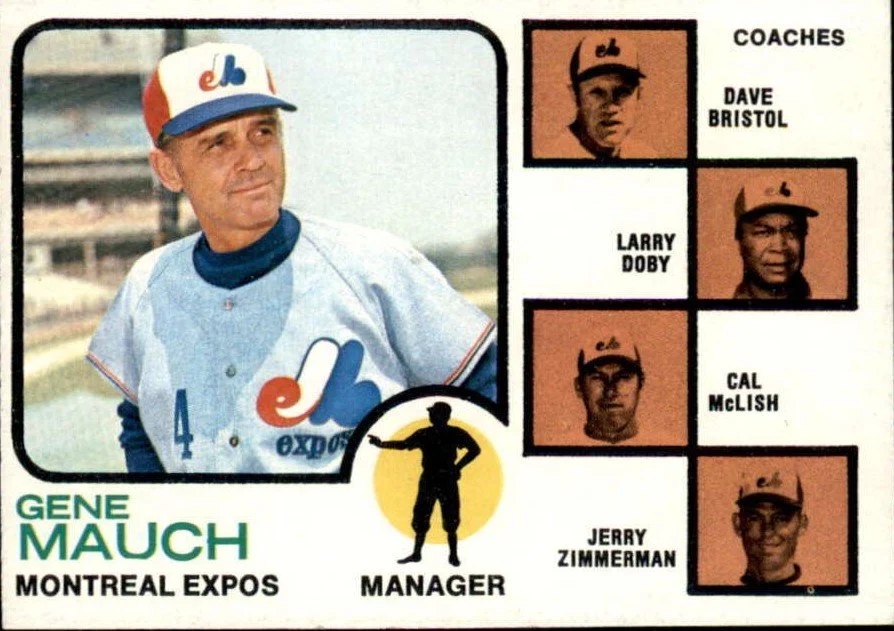

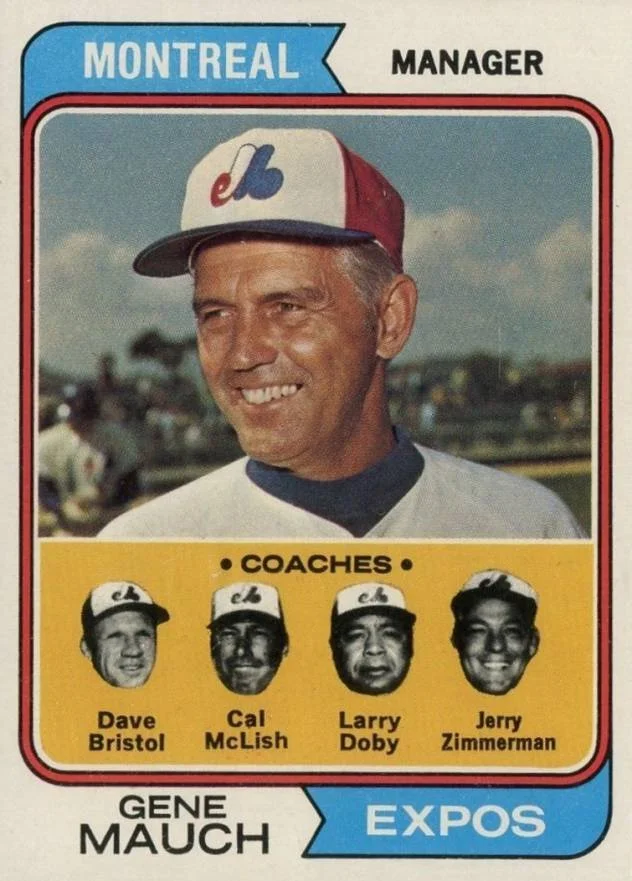

The Montreal Expos 1973 coaching staff.

Ken Singleton was one of the players that benefited from Doby’s advice. After he belted two homers in a game on August 29, 1972, Singleton credited Doby for his success.

“At last, I’m hitting the ball the way Larry (Doby) has been after me all year to do,” Singleton told the Montreal Gazette after the game.

Doby had instructed the switch-hitting Singleton to “lean into the ball” instead of pulling his body away towards the base lines.

But Doby customized his advice for each hitter. For example, he encouraged batters with less power than Singleton – like Ron Hunt and Boots Day – to sometimes “punch” at the ball to make contact.

“It takes a discipline hitter to do that,” Doby told the Montreal Gazette about this approach. “We’re trying to work on several of our players to hit like that. It’s not easy. The natural thing to do is swing. And you have to convince them that they are tailored to hit that way.”

In 1973, the Expos players created the Larry Doby Golden Bat award that they would present to the team’s top hitter after each game. The award was an old bat that would be strung up in the winning player’s locker.

At the end of the 1973 season, Doby made it clear that he had ambitions to become the first African-American manager in the big leagues.

“I’ve paid my dues and I think I’m the best qualified,” Doby told Montreal Gazette reporter Tim Burke in an article published on September 28, 1973. “I can manage a game and I can handle men.”

Doby believed that, with five seasons of coaching experience under his belt, he had matured.

The 1974 Expos coaching staff.

“For the last three years, I’ve been with Gene Mauch, the best mind in baseball,” Doby told Burke. “I’ve profited immensely from just watching that man in action . . . I don’t think Mauch would have me around if I didn’t know my baseball.”

So, as noted earlier, with an ambition to manage, Doby left the Expos to become the hitting instructor with Cleveland in 1974. It seemed like a perfect fit: he was going back to the team he made history with and their manager was less entrenched in his position than Mauch.

But that season turned out to be one of the most difficult of Doby’s career, and after Cleveland opted to hire Frank Robinson as their player/manager in October 1974, Doby returned to the Expos as a roving hitting instructor in 1975.

In that position, he had a profound impact on two of the Expos’ best young players. Ellis Valentine shared how important Doby was to him with Jonah Keri for his 2014 book, Up, Up & Away.

“One of the best years I ever had was in Memphis at Triple-A,” said Valentine. “Doby was the hitting coach. I had somebody to talk to, to mentor me. It was the most sane freaking year of my baseball career, even though I was only 19 years old. I could talk to him at games, go to breakfast, talk to him on the plane, on the bus. That meant a lot.”

Andre Dawson also praised Doby, who had worked with him in Instructional League in 1975.

“I have to give him a lot of credit for whatever success I have,” Dawson told the Montreal Gazette in July 1977.

Doby was elevated to Expos big league hitting coach again in 1976 where he continued to work with talented youngsters like Larry Parrish and Gary Carter.

As noted earlier, after the Expos lost 107 games and hired Williams following that season, Doby departed and became the batting coach with the White Sox under manager Bob Lemon. After Lemon was fired in June 1978, Doby finally got his wish and became the second black manager in MLB history. Doby led the team to a 37-50 record, but was not re-hired after the season.

Doby later worked in various roles in baseball, including as a special assistant to American League president Gene Budig in 1995.

In 1997, Cleveland retired his No. 14 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of him breaking the American League’s colour barrier and the following year, he was elected the National Baseball Hall of Fame by the Veterans Committee.

Five years later, after battling a number of health issues, including kidney cancer, Doby passed away at the age of 79. The baseball community mourned his death, and among those that would miss him the most were the Expos players he influenced and the fans and friends he connected so deeply with in Montreal – a city he once called “like home.”

“The people in Montreal have been just wonderful,” Doby told the Montreal Gazette in December 1973. “I mean the baseball people and you media people and all the friends I made. It’s been just wonderful.”