Glew: Remembering Rico Carty

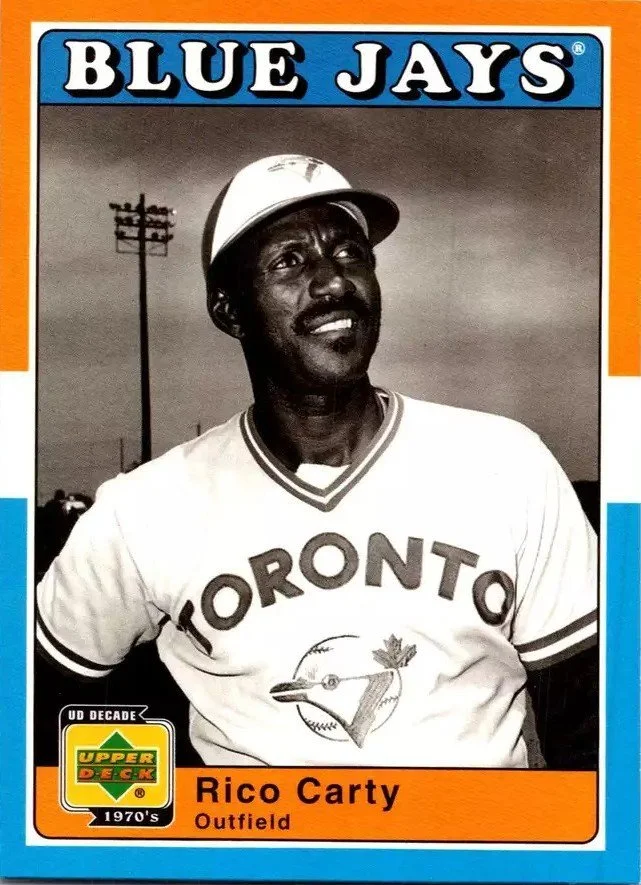

Rico Carty played parts of two memorable seasons with the Toronto Blue Jays.

December 13, 2024

By Kevin Glew

Canadian Baseball Network

Fifteen years before Rickey was being Rickey in Toronto, Rico was being Rico.

Rico Carty, like Rickey Henderson after him, had a propensity to talk about himself in the third person.

“They think Rico is through, but he’s not,” Carty proclaimed to reporters after Cleveland dealt him to the Blue Jays on March 15, 1978. “I will show Toronto fans that Rico can still hit.”

And he certainly did.

But also like Henderson, almost anyone around Carty during his short tenure with the Blue Jays has a story about the eccentric slugger.

“Rico was a first-class guy,” recalled Vancouver native Dave McKay, who suited up on the Blue Jays with Carty in 1978 and 1979. “But I remember he played with his wallet in his back pocket . . . Rico didn’t trust [other people’s] safes or anything like that. He was convinced someone was going to steal his wallet. So, he always played with this bulge in his back pocket.”

Perhaps this explains why broadcaster Tom Cheek would see Carty with so many keys.

“I remember Rico always looking like a janitor,” wrote Cheek in his 1993 biography, Road to Glory. “He would walk around with this big wad of keys dangling from his belt, and no one knew why. People used to look at him and say, ‘Nobody has that many locks!’ But there was Rico, clanging away as he went from place to place.”

Marysville, N.B., native Paul Hodgson, who was in Blue Jays camp with Carty in 1980, can recall playing cards in the slugger’s hotel room at the Ramada Inn Countryside in Clearwater, Fla.

“I walked in and the windows were open and there was Rico and Big John Mayberry with no shirts on and it was at least 95 degrees in there,” remembered Hodgson. “And Rico had the Dominican music going . . . And I sat on a bed and they poured me this drink of tequila and I remember there was a worm in it.

“And I thought this was pretty surreal. Rico Carty and Big John were legends, and these two guys were just sitting there ribbing each other, telling stories about anything and everything and drinking the tequila. And there was the music and the heat. And you know what? It was fantastic. It was a like a movie scene.”

Carty’s teammates have been reminiscing about him since he died on November 23 in an Atlanta hospital at the age of 85. He had been battling intestinal ailments.

Carty, who often referred to himself as “Beeg Boy” or “Beeg Mon,” spent less than two of his 15 big league seasons with the Blue Jays, but it was long enough for him to become the first Jay to belt 20 home runs in a season and the first to sign a long-term contract with the club.

And for a short stretch in the late 70s, Carty was one of the most popular athletes in Toronto. Known for his wide smile and for bantering easily with fans, Carty was also prideful and rebellious. For example, the Blue Jays wanted to him to play winter ball prior to the 1979 season and he refused. He also regularly skipped pre-game drills.

The veteran slugger also brought with him a reputation for being injury-prone, one that proved to be warranted. In 1979, he complained that his swing was hampered by a sliver in his finger that he got from sticking his hand into a stash of toothpicks in his luggage bag on a road trip. However, rather than having the sliver removed, Carty insisted on using Epsom salt to clean the wound and that the sliver would exit on its own.

Prior to acquiring him, the Blue Jays’ brass would’ve heard stories of Carty’s feuds with teammates (including Hank Aaron), umpires, managers and executives. But they needed some star power, not to mention some pop in the middle of their lineup and they figured it was worth rolling the dice on Carty.

A catcher in his youth

Born in 1939 in San Pedro de Macoris, D.R., Carty was a catcher for much of his youth. His play for the Dominican Republic in the 1959 Pan Am Games attracted the interest of the Milwaukee Braves who signed him that same year.

He suited up for class-D Davenport and class-C Eau Claire before he enjoyed a breakout campaign with class-B Yakima in 1962, batting .367 with 17 home runs in 108 games.

The following year, Carty competed in 21 games for the triple-A Toronto Maple Leafs, but he struggled defensively behind the plate, so the Braves sent him down to their double-A affiliate in Austin to learn to play the outfield. While learning his new position, Carty batted .327 and had 27 home runs, which earned him his first big-league call-up that September.

National League Rookie of the Year candidate

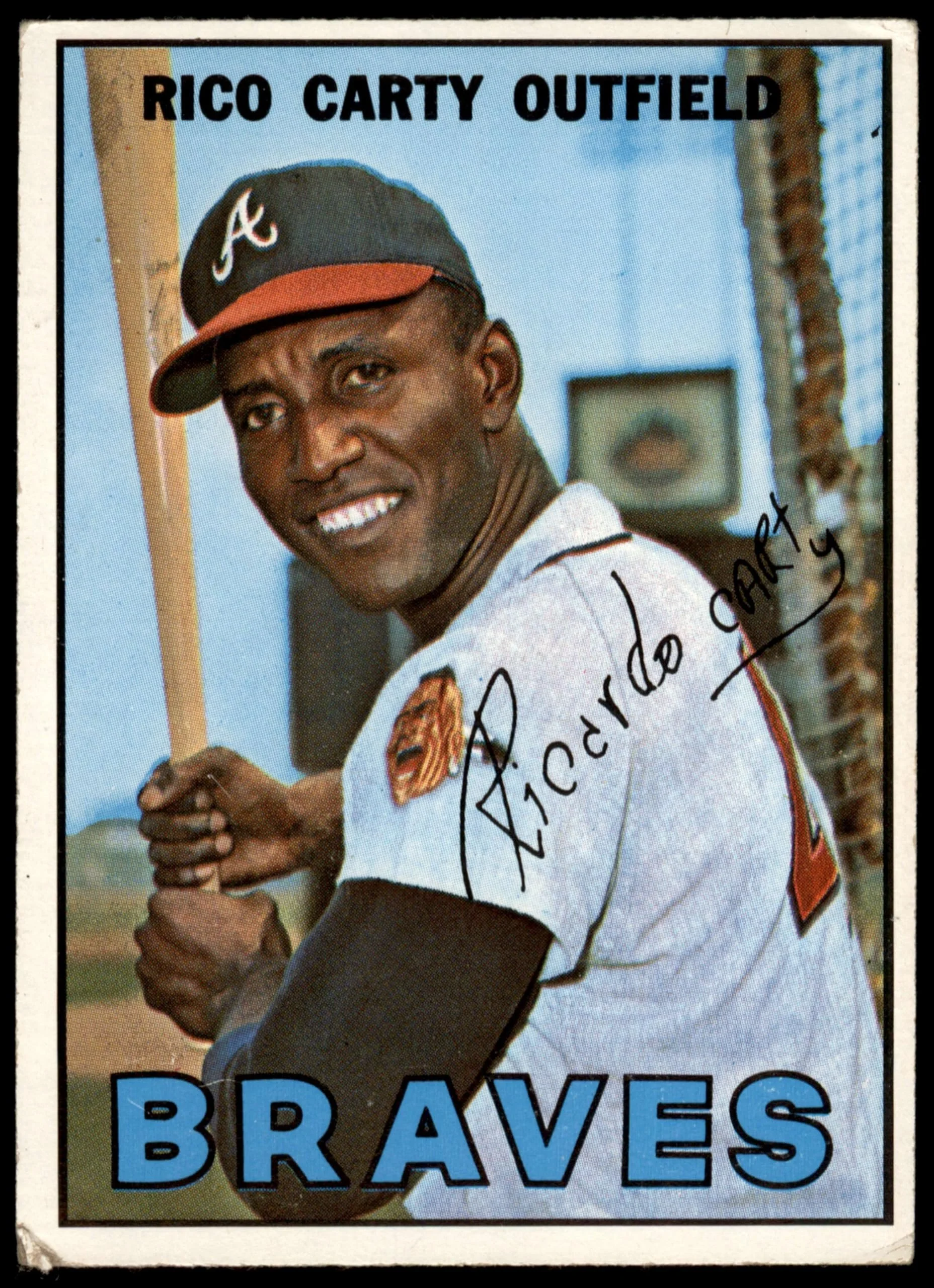

In 1964, Carty won the Braves’ starting left field job and hit .330 and socked 22 home runs to finish second in the National League Rookie of the Year voting.

Unfortunately, a back injury would limit him to 83 games in 1965 but he rebounded to play more than 130 games in the next two seasons before missing all of 1968 with tuberculosis.

Carty returned to bat .342 with 16 home runs in 104 games in 1969 and then win the National League batting title the following season. Looking to maintain that elite level, he then played winter ball in the Dominican Republic where he fractured his knee and missed the entire 1971 campaign.

Back in the Braves’ lineup in 1972, he hit .277 in 86 games but he wasn’t getting along with Braves’ general manager Eddie Mathews, so Carty was dealt to the Texas Rangers following the season.

Didn’t want to DH

With the Rangers, the defensively challenged Carty seemed to be an ideal DH or so Rangers manager Whitey Herzog thought until he approached Carty with the idea. Carty strongly disagreed. He felt he could still contribute defensively in the outfield. Carty and Herzog clashed and the veteran slugger batted just .232 in 86 games with the Rangers before his contract was sold to the Chicago Cubs.

He appeared in 22 games with the Cubs prior to being flipped to the Oakland A’s on September 11. He competed in seven contests for the A’s.

After shuffling between three major league teams in 1973, Carty signed with Cordoba of the Mexican League and batted .354 with 11 home runs in 122 games, which convinced Cleveland to sign him.

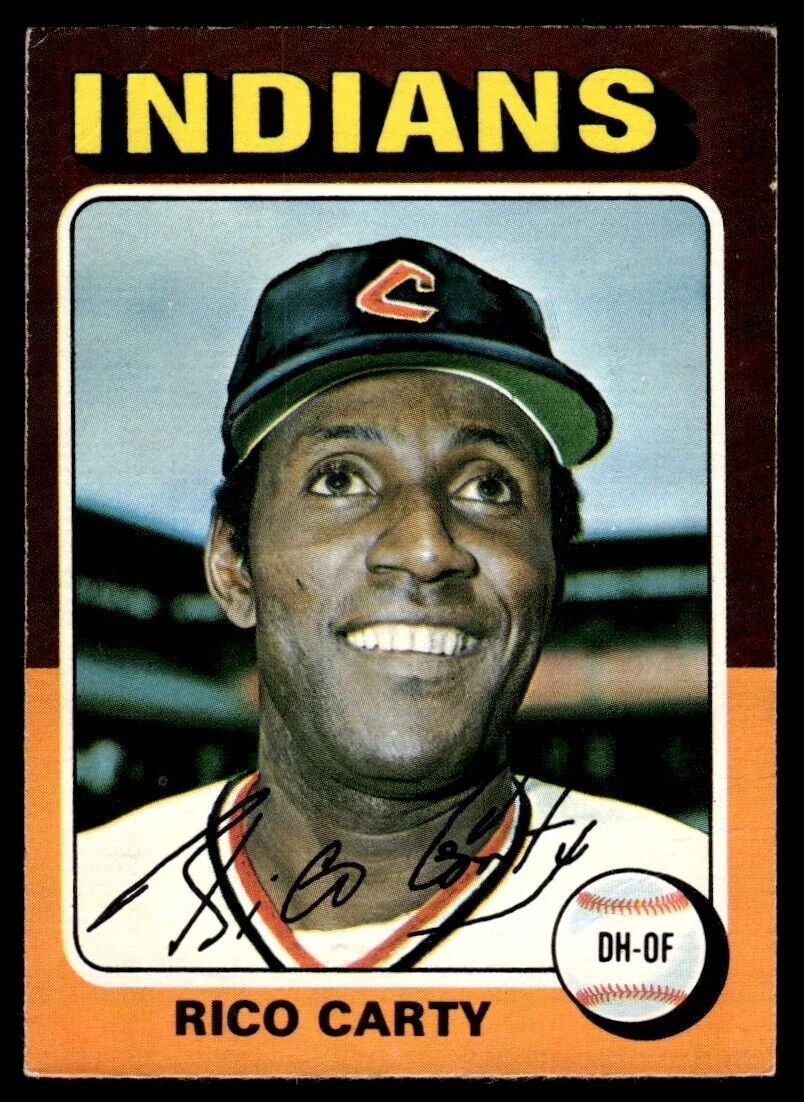

Serving primarily as a DH, Carty had back-to-back .300 seasons with Cleveland but he feuded with manager Frank Robinson. Despite a solid 1976 campaign in which he led Cleveland in hits (171) and RBIs (83), the team left him unprotected in the American League Expansion Draft that November and he was selected by the Blue Jays.

Arrives in Toronto

Just over one month later, the Blue Jays traded him back to Cleveland for catcher Rick Cerone and utility player John Lowenstein. Carty proceeded to bat .280 with 15 home runs and 80 RBIs in 127 games with Cleveland in 1977 before he was dealt back to the Blue Jays the ensuing spring.

“Why do they want to trade Rico?” the 38-year-old Carty said with tears in his eyes while talking to the News Journal (a Mansfield, Ohio paper). “I love Cleveland. The people there love Rico.”

But the veteran slugger showed up at Blue Jays camp in Dunedin, Fla., with a smile on his face and he quickly endeared himself to his teammates.

McKay remembers being awed at how hard Carty could still hit the ball.

“He was a line drive hitter and he hit hard line drives,” recalled McKay.

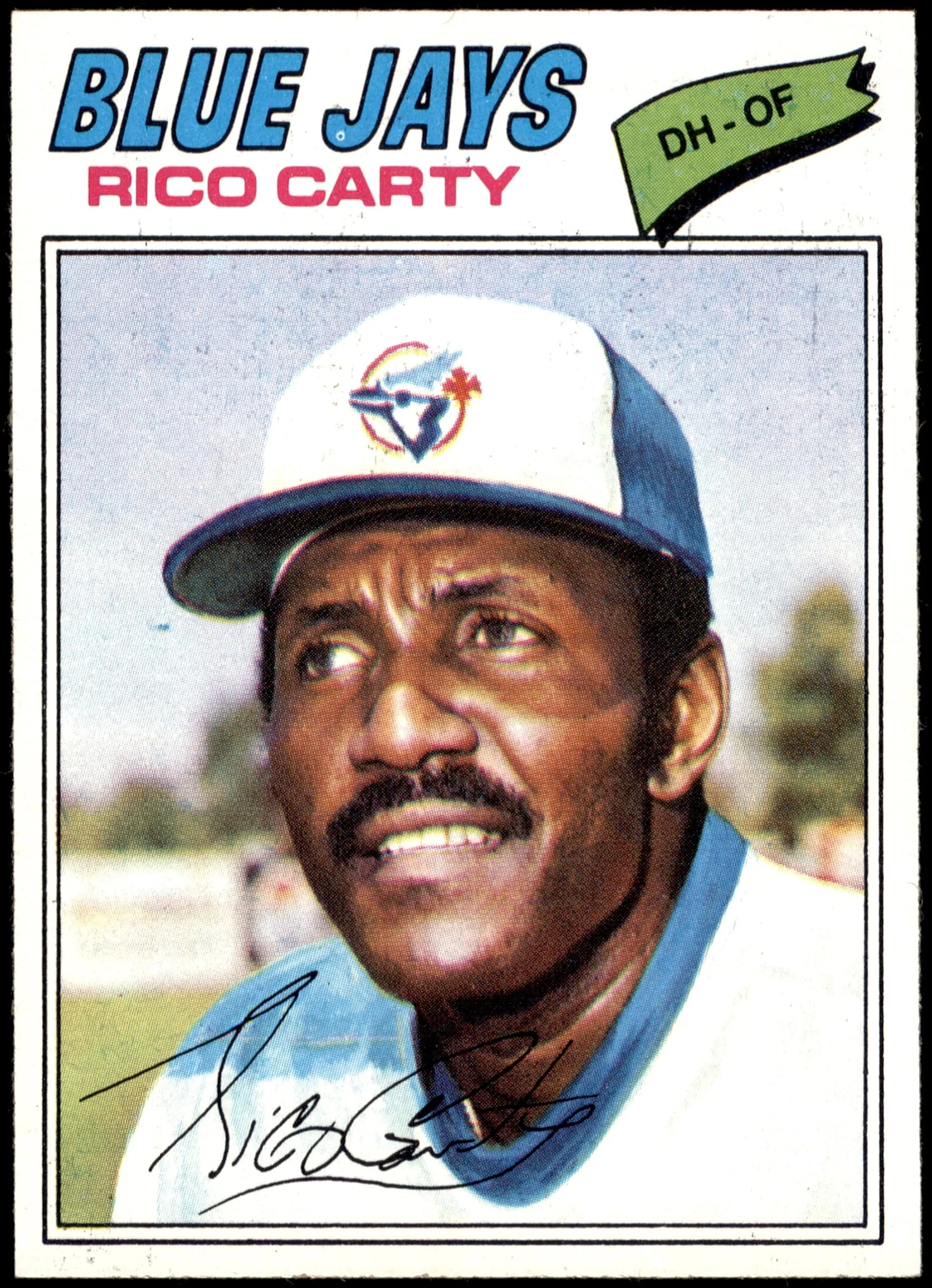

In 104 games with the Blue Jays in 1978, Carty batted .284 and on August 11th he became the first Jay to belt 20 home runs in a season.

Four days later, the Blue Jays traded Carty back to the A’s for Willie Horton and right-handed pitching prospect Phil Huffman. Carty was not pleased.

“I was there once and he (A’s owner Charlie Finley) didn’t treat me right,” said Carty.

To his credit, Carty put his hard feelings aside and clubbed 11 home runs for the A’s down the stretch.

The Blue Jays then reacquired Carty after the season and signed him to a five-year (partially guaranteed) contract that was reportedly worth $1.1 million.

The 39-year-old Carty’s batting average dipped to .255 in 1979 and he only hit 12 home runs in 132 games. He attributed some of his hitting woes to the toothpick injury he sustained in early July.

Determined to redeem himself, the then 40-year-old Carty came to camp early the following spring and was hitting the ball well. Hodgson can vouch for this. He was asked to play third base while Carty took some batting practice.

“Pat (Gillick) says, ‘Why don’t you go down there and take some balls off Rico’s bat?’ So it was Epy Guerrero throwing to one of the hardest line drive hitting son of a guns that has ever played Major League Baseball. And here was me down third at third base. And I’m thinking ‘Jesus, just don’t hit one at me,’” recalled Hodgson.

“So, I was doing OK and we were probably about 20 swings in and he hit a ball that was going to short hop me and I remember diving out of the way like it was a grenade . . . He hit that ball so hard . . . And that was the last time they ever had me stand at third base to take ground balls. I can still remember Epy and Rico laughing.”

Unfortunately, the aging Carty didn’t hit many more balls hard that spring and the Blue Jays released him on March 29.

“Every ballplayer knows that one day he’s going to be released,” Carty told the Toronto Star. “But it didn’t even come close to my mind that it would be like this. They didn’t even let me start the season. If I started the season and I didn’t do well and they released me, I’d understand, but they didn’t give me a chance.”

The release spelled the end of Carty’s major league career. He finished with .299 batting average with 1,677 hits – including 204 home runs – in 1,651 games.

Following his playing days, he served as a Latin American scout for the Blue Jays for a stretch. He also started the Fundacion Rico Carty, an organization that helped people living in poverty in the Dominican Republic.

In retirement, Carty was notoriously difficult to get in touch with, but every once in a while, a reporter would track him down.

In 2019, a Forbes magazine writer asked him how he and the superstars of his era would fare against today’s pitchers who throw harder.

“You think Hank Aaron, Willie Mays, Dick Allen, Roberto Clemente, Orlando Cepeda couldn’t hit this pitching?” Carty fired back. “I’d kill it.”