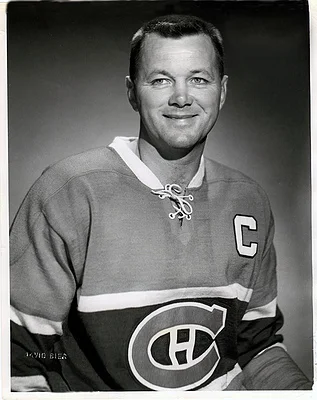

Doug Harvey: HOF defenceman a Border League bopper too

Doug Harvey – We forget he played baseball too

By Bill Young

Canadian Baseball Network

In his classic book Over the Fence is Out, esteemed Canadian sports writer and broadcaster, Jim Shearon, somewhat rhetorically posed the following question: “Was Doug Harvey Canada’s greatest athlete of all time?” Rhetorically, that is, because he had already come up with the answer.

Shearon points out that Harvey, regarded by many as hockey’s greatest defenceman, was also a boxing champion, a topnotch football player and arguably the best of the Canadian contingent in baseball’s Class C Border League.

In fact, he was so proficient at the summer game that several minor-league scouts linked to big league clubs anxiously sought to sign him up.

From the tail end of the 1947 season into 1950 Harvey was a key member of the Border League’s Ottawa Nationals. Composed of teams from Ottawa and Kingston and four New York-based clubs (Auburn, Geneva, Ogdensburg and Watertown), the Border League was one of the many minor league circuits that blossomed following World War II.

When it came to baseball Harvey was special. For starters, except for the sandlot baseball he played as a kid, his entry into pro ball with Ottawa was his first serious contact with the game.

He did not disappoint.

Harvey grew up in the Snowdon district of Montreal, a hotbed of sporting activity. Always an outstanding hockey player, he devoted summers to softball, or to be more precise, fast-pitch softball, or fastball. The best of the best made it to the elite Snowdon Fastball League, and that included Harvey.

Playing for St. Augustine’s parish, he was described as “a line-drive hitting third baseman,” in what author Bill Brown called an “extremely competitive league.”

In fact, as the long-time Toronto Maple Leaf and Boston Bruins stalwart Fleming Mackell, himself a son of Snowdon, recalled, Harvey was so good that occasionally he would travel to the Ottawa-Hull area to moonlight with a team from Hull. Mackell was a frequent travelling companion, as was Habs goaltender Bill Durnan, counted among the most dominant fastball pitchers in Canada.

Mackell, now deceased, spoke fondly of those days when their wee group would follow old Highway 17 as it dipped and dove alongside the Ottawa River, passing through countless towns and villages en route to the nation’s capital. Their favourite rest-stop was in the town of Alfred, just upriver from Hawkesbury, where, recalled Mackell, “Durnan would nod and quietly say: ‘Time for a break. Let’s pull over. I need a beer.’” In fact, the goalie would order two big ones, what we used to call quarts. Durnan insisted the ale served to help loosen his arm.

“It must have worked¸” added Mackell. “I can’t remember Bill ever losing a game.”

In 1947, when Harvey was playing fastball in Hull, he was spotted by Tommy Gorman, one of hockey’s early giants and at the time owner of the Ottawa Nationals baseball club. Gorman was taken with young Doug’s natural ability, and without hesitating a moment, he offered Harvey a place on his ball team.

Always his own man, and ready for any challenge, Harvey accepted. As might be imagined, he received a cool welcome in the clubhouse. Most upset was Nationals’ manager Paul Dean. (Sometimes referred to as “Daffy”, this Dean was a successful major league pitcher and the lesser known brother of Hall of Famer Dizzy Dean. In 1934, Paul and Dizzy each won two games for the World Series Champion St. Louis Cardinals, thus fulfilling Dizzy’s ‘me ‘n’ Paul’ prediction and giving rise to a catch-phrase still heard today.)

As a manager, Paul Dean was old-school. Baseball was a serious business, and he had little room for the sort of gimmicky foolishness imposed on him by Gorman.

The players, mostly American, were of similar bent, tending to mock Harvey, making fun of his tacky glove and awkward batting stance. In their eyes, they were the pros: he was just an interloper who didn’t belong.

Fortunately teammate Bill Metzig saw something more in the rookie. He helped guide him through all the required steps until toward the end of the season, when Harvey finally entered his first game, he was ready.

Indeed, so much so, that he set the tone of the match, hammering out two solid if unexpected hits the first chance he got.

In the 10 games remaining, Harvey was a hit machine, putting together a batting average of .400. Coincidently or not, in 1947 the Ottawa nine won both the league championship and subsequent ‘four-club playoff series’.

But by then Harvey was already back in Montreal hoping to catch on full time with the Canadiens. In fact, his season was an up-and-down sort of affair, with him splitting playing time between both Montreal and Buffalo.

###

Lansdowne Park in Ottawa, Ont. circa 1950

Home for the Ottawa Nationals was Lansdowne Park, a playing field designed for football, and not especially accommodating for baseball. As the accompanying photo shows, the third base line ran parallel to the North Side, and there was almost no room in foul territory. However, as Shearon points out in his book, between the lines the fielders had to cover a great deal of ground. And the outfield – it ran halfway to the Rideau Canal.

But it was here, in 1948 and ’49 that Harvey enjoyed two years of glorious success. Much of that is attributable to teammate and newly appointed playing manager, Bill Metzig who had replaced the surly Paul Dean following the ’47 season.

Metzig, a potent Punch and Judy type of hitter, good enough to finish second in the 1948 batting race, soon recognized the potential hidden beneath his protégé’s rough edges, and carefully, patiently, began guiding Harvey through the niceties of the game. According to Brown, when Metzig assigned Harvey to be his right fielder, the pilot described him “as a steady fielder: he covers a lot of ground.”

And he could hit the ball. Following Harvey’s passing in 1989, Eddie McCabe, long-serving scribe for the Ottawa Citizen, described Harvey as possessing extraordinary hand-eye coordination and excellent power. He singled Harvey out as one of the [Nationals'] major weapons.

In 1948, Harvey played in 109 of the scheduled 127 games, emerging as a legitimate star. At season’s end he boasted a record of 22 doubles, 16 triples and 73 runs batted in – along with a .344 batting average, fourth best in the league. Although the Nationals finished the season as league champions, they were quickly eliminated in the first round of the playoffs, falling to Ogdensburg, four games to one.

And once again, Harvey rushed back to Montreal and hockey, determined that in this, his first full year with the big club, he would make his mark.

###

As good as Doug Harvey was in ’48 he was even better the following year, especially as he didn’t even join the team until 20 games into the season. To no one’s surprise, given Harvey’s track record, in the eighth inning of his first game back, he was the one who hit the single that broke up the opponent’s no-hitter and then scored the run that erased the shutout.

His teammates were amazed, wondering how this guy could just walk onto the field, 20 games into the season, and play like he’d never been away. As Brown noted, “what had he been up to while they were sweating it out at spring training?”

Playing in 109 games once again, Harvey not only won the batting crown with a .351 average, he also hit with greater power, leading the league in runs batted in (109) and runs scored (121).

And the Nationals, though finishing second, topped the league in both hitting (team average .286), and attendance, with 78,577 souls passing through the turnstiles. Once again, however, the Nationals failed to advance in the playoffs, losing this time to Auburn, four games to three.

And with that, as hockey took up more of his attention, Harvey’s professional baseball career slowly drifted toward its inevitable conclusion. Ironically, by this time he had caught the eye of several minor league scouts determined to get his signature on a contract, notably representatives of the then Boston Braves, Boston Red Sox, and the St. Louis Cardinals. They were not easily dissuaded.

Tempted but not really interested, Harvey rejected all offers, although he did seriously ponder one that promised promotion to class-B ball. He later intimated that had he been invited to play at the triple-A level instead, he might have given more thought to the invitation.

Harvey did return to Ottawa for the 1950 season but after 10 games he realized his heart wasn’t in it. And besides, the management side of the Canadiens wanted him home. They were tired of having to hold their collective breath every time he took to the diamond, chillingly fearful that just as their stellar young defenceman was about to reach his potential he would suffer a serious, perhaps even career-ending, injury.

For Harvey was on the cusp of becoming one of hockey’s all-time defensive icons. Not only did he lead the Habs to six Stanley Cups, he was instrumental in forcing the NHL to change one of its fundamental rules pertaining to penalties and the resulting ‘man-advantage” situation.

Because Montreal was so adept on the power play, sometimes scoring two or even three goals on one, two-minute penalty, the NHL, in 1956, issued the following amendment:

If while a Team is “short-handed” by one or more minor or bench minor penalties, the opposing Team scores a goal, the first of such penalties shall automatically terminate.

###

Although Harvey set aside professional baseball once and for all in 1950, he still kept active on the diamond, playing in the Snowdon Fastball League, as well as with the Canadiens travelling softball (i.e. fastball) team. Barnstorming across the province on public relations jaunts, competing against local all-star teams in such modest communities as Trois-Pistoles and Ste. Anne de Bellevue, the Habs seldom lost. Their pitching was too good – especially as they tended to rely on ringers to secure the win.

In the end nobody cared. They all were looking forward to the post-game reception at the local brasserie, with its singular opportunity of downing a cold one while rubbing elbows with living, breathing members of les Canadiens and fêting the team many claim was the best the hockey world has ever seen.

Doug Harvey also had something to do with that.

And, by the way, Jim Shearon. In case you were still wondering, he did indeed decree that “Doug Harvey should be recognized as Canada’s greatest athlete of all time.”

Sources:

William Brown, DOUG, The Doug Harvey Story, Montreal, Véhicule Press, 2002

Jim Shearon, Over the Fence is Out! The Larry Walker Story and more of Canada’s Baseball Legends, Kanata, Marlin Head Press, 2009

J.G. Taylor Spink, Official Baseball Guide, St. Louis, Charles C. Spink, 1947,’48,’49,’50’

Fleming Mackell (Interview with Bill Young, 2009)