Bonds helped put Ottawa-based bat manufacturer's maple bats on MLB radar

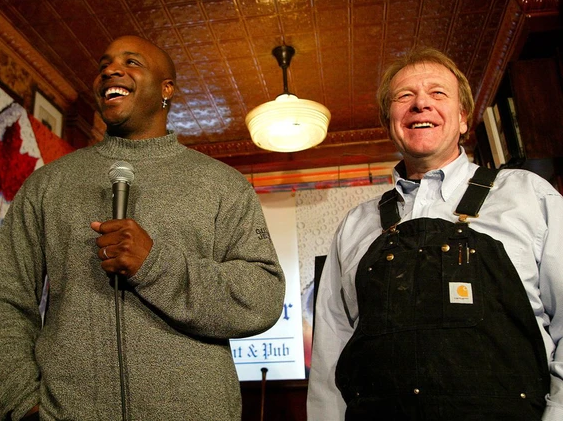

Major League Baseball slugger Barry Bonds on one of his visits to Ottawa to see Sam Holman, who made Bonds' bats out of maple. Photo: Jean Levac /Postmedia Network

March 19, 2022

By Patrick Kennedy

Canadian Baseball Network

Barry Bonds, eyes widened as if recognizing a hanging curveball bending into his wheelhouse, stared with childlike wonder at the dozens of baseball bats scattered about a living room in the heart of Ottawa.

Bonds turned to his host, carpenter Sam Holman, and exclaimed, “This is like being in a candy shop!”

That visit took place in January 2002, just a few months after the mercurial San Francisco Giants superstar hit 73 home runs to set a new single-season record. While on route to New York to collect his fourth of a record seven MVP awards, Bonds had made a pitstop in the Canadian capital to offer personal thanks to Holman, a former stagehand at the National Arts Centre who played a role in helping Bonds establish that astounding standard - and in time the career home run mark (762) as well.

“I take pleasure in knowing I share those records,” Sam explains on the phone to a caller from Kingston a score of years later. “Barry made the records; I made the instruments.”

The instruments, of course, were the Sam Bats - in Bonds’ case the 2K1 model, a tapered 34-inch piece of maple weighing precisely 31.6 ounces, just one of a variety of maple bats produced by the business that Sam founded 25 years ago, The Original Maple Bat Company.

In 1997, the Sam Bat became the first maple bat used in big-league competition, a then-unlicensed club snuck into a game by Toronto Blue Jays World Series hero Joe Carter. More in a moment on those baptismal swings through the strike zone and on Carter’s later Cupid-playing role in matchmaking Miss Maple with Mr. Bonds.

The maple bat broke with baseball tradition, no small feat in a sport that is stubbornly affixed to ritual and custom. Before the arrival of Holman’s namesake bat, most bats were made from white ash. Today, the opposite rings true. Approximately 75 percent of all bats sold to baseball’s professional leagues are now made from maple. The Sam Bat blazed that trail.

If imitation is the highest form of flattery, the Original Maple Bat Company is awash in compliments. Last year there were 32 companies licensed to make bats for major league and minor league players, up from 10 in 1993. This year there are more than 40, and that doesn’t include small start-ups such as Kingston’s Limestone Bat Company. Virtually all use maple as the raw material.

Sam Holman, who’s now 77 and recuperating from a November quadruple bypass operation, recalls how the idea for a new-and-improved bat flew out of a beer mug one night in an Ottawa oasis in 1996. Holman’s friend Bill Mackenzie, the Nova Scotia-born ex-Detroit Tigers prospect who would spend 35 years in professional baseball, had just returned from Spring Training. There he noticed how often ash bats were breaking. Mackenzie challenged his pal to come up with a more resilient replacement for ash.

“I asked Sam to see if a more durable wood could be used,” Mackenzie, 75, remembers recently from his home in Brockville. “Sam took the bit and ran with it, researching the different kinds of wood.”

After meticulously studying various tree species, Holman – he famously remarked “I knew I wasn’t going to make a better ash tree” – decided on maple, but not just any maple, mind you. It had to be rock maple, a.k.a. sugar maple, with straight grain and minimal flaws, the hardest and densest of the species.

“He brought me a couple of early samples that were, shall we say, a bit off in size and shape,” Mackenzie recalls with a laugh. “But he kept persevering.”

In 1997, Holman managed to put Sam Bats in the hands of Blue Jays players Carter and Ed Sprague during a team workout at the SkyDome. One year later, Carter, having moved on for a brief stint with the San Francisco Giants, introduced new teammate Bonds to the Sam Bat.

Sprague, the Oakland A’s director of player development, recalls those first swings with maple over the phone from the A’s training facility in Arizona.

“The hardness of the maple was different, the bat didn’t flake or dent, and the ball came off the bat differently,” he says.

Sprague, whose memorable ninth-inning, pinch-hit home run won Game 2 of the 1992 World Series, says maple’s hardness could sometimes result in a quirky oddity: “The bat was so hard, you could hit a ball on the barrel and still break your bat,” notes the former 11-year big leaguer. “I remember once hitting a home run, and all I had left in my hands was the handle.

“The timing was right (for a change in wood),” Sprague adds. “And once Joe gave a Sam Bat to Barry Bonds, well, it’s never a bad thing to have one of the game’s greatest hitters use your bat.

“Sam opened the door for a lot of bat manufacturers.”

Giants’ linchpin Bonds became the Carleton Place-based company’s best client among the dozens of big-leaguers who have used, and continue to use, the Sam Bat. The list includes such high-profiled players as Albert Pujols, Alfonso Soriano and Ryan Braun, to name a few.

In 2012, Detroit Tiger Miguel Cabrera swung a Sam Bat while becoming the first player since 1967 to earn baseball’s elusive Triple Crown of hitting. When Blue Jay Jose Bautista set the franchise home run record in 2010 (54), he wielded a Sam Bat. Not surprisingly, in 2003 - the year after Bonds set the new single-season home run mark - the Original Maple Bat Company doubled its production.

Today, the Sam Bat is exported to several baseball-loving countries. It’s the preferred choice of lumber for more than 100 professional players.

The Sam Bat’s creator, Samuel Holman III, was born in Kansas, the oldest of five children whose father was a veterinarian and veteran of the WW II battle of Iwo Jima. The family later moved to South Dakota. Sam, who worked Ottawa’s NAC for 23 years, says his maternal grandfather instilled in him a lifelong love of carving and carpentry. Grandpa also took 10-year-old Sam to his first big-league tilt between the hometown Kansas City A’s and the formidable New York Yankees of Stengel, Mantle, Ford, Berra and Co.

“And the A’s won that day,” Sam quickly confirms 67 years later.

In 2007, Holman sold his majority share in the business he started to current company president Arlene Anderson and her husband Jim. If he hadn’t taken on partners, Holman, the quintessential workaholic, believes he’d be pushing up daisies today.

“I was consumed by the job, working 24/7. I was almost dead by the time Arlene and Jim came on as partners,” says Sam.

“I never made a dime,” he fibs innocently. “I mean I got by, but people who work out of their garage and home day and night don’t become cigar-smoking captains of industry.”

Maybe not, but sometimes they do shake up a rigid, ages-old industry, and in the process, they change a tried ‘n true tradition for the better.

“Sam Holman revolutionized a significant part of the game,” Sprague points out. “Not many people get to do that.”

Patrick Kennedy is a retired Whig-Standard reporter who takes occasional cuts with his 1966 ash-made Tony Oliva model Louisville Slugger. He can be reached at pjckennedy35@gmail.com.