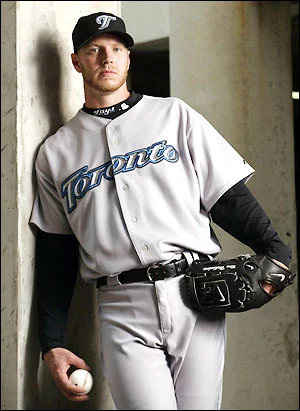

Remembering Doc: Likely HOFer Roy Halladay's roots trace to Colorado

*With the late great Roy Halladay seemingly on the cusp of being elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame, we wanted to take a look back at how his Cooperstown-worthy career began. Canadian Baseball Network editor-in-chief Bob Elliott wrote this article back in May 2006.

Originally published May 20, 2006

By Bob Elliott

DENVER, Col. _ Roy Halladay was in a jam.

His eighth grade teacher at Drake Elementary School had given the class an assignment:

Write an essay on what you want to be when you grow up.

That wasn’t the problem.

The difficulty came when the teacher added the caveat ... “don’t be submitting any silly goals ... I don’t want to read how you want to be President, or a pro athlete.”

Halladay returned home and explained the Catch-22. He could write it, since he knew what he wanted to write and at the same time he could not.

“I called the teacher,” Roy Halladay’s father, also named Roy, said this week. “The teacher said she wanted the children to be realistic. I asked why take dreams away? Whether kids fulfill their dreams is not up to you, its up to them.”

The teacher changed her mind. Roy Halladay finished his essay, accompanied by a poster of a ball player.

“The biggest problem with Roy growing up was not his ability,” said the father. “It was people saying to him ‘do you realize how hard it is to make it?’

“I used to tell him he couldn’t listen to these people, you can do anything you want to do.”

And a lot of nights, Harry Leroy Halladay III, Blue Jays ace, does anything he wants against opposing pitchers. He’s fulfilled and surpassed an eighth-grader’s dreams and just turned 29 five days ago.

The former No. 1 pick of the Jays has a Cy Young award on his resume and an 84-44 record (a .656 winning percentage).

These words are not about Halladay’s first-pitch strike efficiency or his ability to work on three days rest. This is about Halladay’s early, Wonder Bread years and how he grew up to be such a wonder.

How he went from taking batting practice at neighborhood park in suburban Arvada with mom Linda and pop Roy taking turns throwing batting practice, with older sister Merinda and younger sister Heather, shagging flies to the major-league mounds.

The Jays ace is in Denver for the first time in a major-league uniform. He’ll spend it as a spectator, having started Thursday night in Anaheim.

“It’s a disappointment and a stress relief at the same time,” said Heather, “when I think of people who would have come to see him pitch, from that aspect I’m relieved for him.”

Heather has 30 tickets for each game of the three-game series. Brother-in-law Dustin doesn’t want a seat in the grandstand. He’ll sit in the rock pile in centre with a sign which reads ‘The Doc pile.’”

These are the people who helped make the Halladay homecoming possible.

The Mother

Linda Halladay caught some of Halladay’s first bullpen sessions.

“When he got older, I’d to throw to him,” Linda said. “This was big stuff in our family.”

Merinda, who went to Idaho State University on a basketball and volleyball scholarship and Heather, a fastball pitcher, and dad chased down the fly balls and filled the bucket.

“We never had problems with Roy, he was raised to be a baseball player,” Linda says. “He grew up wanting to please people. As a mother I was very concerned about him being pushed. Mothers worry.”

Linda tried to juggle, searching to find a balance for her son.

“There was pressure to exceed,” the proud mom says, “that’s why I think he does so well -- he’s pitched so long under pressure. If they lost a game, Roy would punish himself.”

When pop was away, Roy did work on his own, throwing 100 pitches at a tire hung in the basement, taking swings off the pitching machine and lifting weights.

“After that, we’d do something for fun, basketball, or swimming,” mom said. “We’d fly a kite, the kind with two handles, so it could do loops.”

Some years playing on three teams -- pitching and playing first base -- he’d miss social events at high school.

Then he’d lay on the couch, his pet hamster, Gizmo, sleeping on his stomach.

Halladay bought his mom a new Chevy Blazer for, well for being mom.

The Father

Harry Leroy Halladay II had his son Harry Leroy Halladay III playing catch at age three and by five, the youngster was playing t-ball.

Halladay’s father played sandlot ball, and describes himself as a strong-armed outfielder.

“I always loved the game,” he said, “I thought we could teach him to harness his ability.”

He bought Nolan Ryan’s Pitcher’s Bible: The Ultimate Guide to Power, Precision, and Long-Term Performance, written by Tom House. The book proposed the use of two pound weights.

Pop, a pilot for Stearns-Rogers Engineering, built an enclosed batting cage in the basement, a pitching machine at one end and a portable pitching mound at the other.

“I’d come home from work and say ‘hey Roy you want hit a bucket of balls?’ and off we’d go, he always enthusiastic,” the father remembers. “We hung out a lot. He was my best friend, until he got to high school.”

Father and son talks evolved around positive thinking since as the father said “adults, kids, parents, everyone was quick to tell what you can’t accomplish.”

The father gave him a wonderful example of how negative waves -- like Donald Sutherland in Kelly’s Hero’s -- can affect someone. At the time Roy was running cross country.

“I told him to run alongside a friend and ask ‘are you feeling OK? Are you sure you’re OK?” Sure enough the other runner slowed down.

“If you tell yourself you are weak you will fall back,” the father said. “Then, he’d come to me and say ‘dad you OK? Are you sure?”

The father approached pitching instructor Bus Campbell when Roy was seven. Campbell said to when the son was 12.

“Bus has the ability to watch everything at full speed but sees things in slow motion,” the father said.

Now a pilot with LePrino Foods, which boasts itself as world’s largest manufacturer of mozzarella and pizza cheese -- the father has watched his son raise his own children. After observing he has said something I have never heard said before.

Roy Halladay, the father, has looked Roy Hallladay in the eye and said: “I wish you were my father.”

The Guru

Campbell, 86, has been Halladay’s mentor since he was 12 years old, no matter who is the Jays pitching coach.

“Dang that Leroy, he’s gettin’ so famous, my phone is ringing off the hook,” Campbell said in a poor attempt at indignation.

Like any good scout Campbell did his advance work for this series. He knows the guard working the third-base dugout at Coors Field. Campbell was there last night, stepped through the camera bay into an area away from autograph seekers.

“Then, Leroy and me sat for a talk,” Campbell said.

He helped Halladay grow to be a 6-foot-6, 225-pounder with solid mechanics and Lake Placid-like composure.

“Leroy’s mom made the best apple pie,” Campbell.

Campbell never charged Halladay or any of his pupils a dime, but he didn’t mind chocolate chip cookies and pie delivered to the tutorials. They’d work out at a high school, at a park “anywhere that was dry” and the Halladay basement when snow was on the ground.

“When he was with the Jays, his last year before moving to Florida I was at a field to meet Roy, I look up and this old bomber flies by,” Campbell recalls. Moments later Roy and his father showed.

They’d flown to a nearby air strip in a Korean war vintage Lockheed P-33 jet, which Roy’s father had restored.

Randy Campbell, Bus’ son, graduated from Stanford University and turned down engineering offers. He came home to Littleton to coach high school baseball and soccer.

He suffered a brain tumor and died at age 36. Halladay donated $1,000 for the scoreboard at Randy Campbell Memorial Field at Heritage High School.

The Son

Linda says her only son has always respected her and describes him as “the perfect child.”

“Give Roy a fishing pole, put next to a pond with a dog by his side and he’s happy,” Linda said. Grandpa Harry Leroy Halladay I, taught him how to fly fish.

“He never caught much fishing: a tree, a boot and once his sister Heather,” mom said.

Heather remembers fishing at the Arvada reservoir and the hook from brother’s cast catching her shirt.

“The only fish he ever caught he named Mr. Blue Gills he made it talk to me, I was seven, for a moment and tossed him back,” Heather said.

Halladay grew up collecting baseball cards -- Nolan Ryan, Dale Murphy and Roger Clemens were his faves and then he was in the same clubhouse as Clemens and facing hitters whose cards he had at home.

He never missed a curfew. He was never grounded. Halladay worked hard. He built things the way he now sets up hitters for pitches.

His uncle Steve brought over what was left of an old MG car, basically a frame and a box of parts. The pitcher worked on the car, restored it, painted it cherry red and once it was running again gave it back to uncle Steve.

Mom watched her son pitch and loved the high school games, except when umpires had bad games, especially one game in Texas.

“There were so many scouts there and you want Roy to do so well,” Linda said. “I got carried away and yelled at the ump. People turned and looked, I knew I needed to stop.”

Linda still her passion when Roy is on the mound.

“Mom was at my house watching and Roy was in a pickle, a tough spot,” said Roy’s sister, “well mom was on her knees screaming at the TV.”

West Arvada High School coach Jim Capra was always on Halladay to ease up on hoops fearing injury.

One day, the Wildcats were on the bus awaiting Halladay the scheduled starter in the state semi-final. Out he came. Limping. Wearing a cast on his leg.

It’s a story Capra still tells. How he “absolutely freaked out” until Halladay bent over and removed the fake cast he borrowed from a trainer.

The Next

Linda Halladay re-tells a story Roy told of his son Braden’s first t-ball game this spring.

Braden asked “Dad, you’re coming to my game right?” Roy said he couldn’t because he was out of town.

Braden said “oh, that’s right, you have a satellite dish, so you can still watch my game.”

When they got to the t-ball diamond and Braden asked his mom, Brandy “where’s my locker? Where’s the bullpen?” Braden was used to going to the major league parks and the Bobby Mattick Training Facility in Dunedin, Fla.

Roy and Brandy’s second son is named Nolan, after Nolan Ryan of course.

The Best Friend

Heather is 4 1/2 years younger but he and the boy who would grown up to be a Cy Young award winner.

As kids, Heather and Ray rode Yamaha mo-peds together through streams (“he’d made me go first, to see how deep it was,”), travel down stream in a leaky boat with Heather bailing water, hunt frogs and look for garden snakes.

Both Roy and Heather had their own pet mouse. Then Roy’s mouse bit the head off Heather’s “so he let me have his mouse.”

Halladay went to his sister’s games and “supported me as any brother would, he never allowed me to slack.”

Sounds like a good big brother. But younger sisters always have the best stories. Like you think Halladay has pinpoint control now? Do you marvel at him painting the corner?

“One night he kept calling me to come into his room, I was busy doing something,” Heather said this week. “Finally, I went to his room, as soon as I opened the door he pulled back a slingshot and hit me in the face with a paper football.

“He said he’d pay me $5 not to tell mom and dad, but I don’t think I ever collected.”

Heather went to Roy’s games, was there for the ride home and quiet rides home after games that went poorly. Heather is still younger, but is no longer a baby sister, with three children of her own, including one son, Dominic.

“My husband, Joe, and I have this conversation on how to raise our son, he wants to push him, I don’t want to,” Heather says.

Sister agrees brother was a diligent worker but blows the whistle on a few nights when Roy was supposed to be lifting. Instead, they’d sit and just ‘goof off and talk.”

That was until they were discovered due to their father’s booby trap.

“Dad put chalk lines on weights so he’d know if they’d been moved,” Heather laughs. “After we found out about the chalk, we’d moved the weights.”

Father flew a private plane taking the whole family to Tampa Bay for Halladay’s first major-league start in 1998.

“I think I cried, when they announced ‘pitching for Toronto ...” Heather said. “To know what he was striving for all those years and see him there. I’m very emotional, I probably cried the whole game.”

Halladay is the best starter on the Jays. Best pitcher on Heather’s ultimate fantasy team?

“Of course it’s my brother,” she says proudly. “I don’t care who else is on my team. I committed $8 million which meant I have a lot of $1 million guys.”

Slowly, but surely Heather is adding players to turn Team Halladay into Team Blue Jays, adding Benjie Molina, Aaron Hill, Alex Rios and Vernon Wells.

“I think he got me negative eight points in his start against Tampa Bay last month, I’m used to getting me 90-to-150 points.

“But I’ll stick with him even if he gives me negative points every time. He’s my brother I love him.”

Like every Blue Jays fan from Port Alberni, B.C. to Corner Brook.