Meet Jim Lawrence: Canada's Moonlight Graham and Caledonia's only big leaguer

Jim Lawrence, the only player from Caledonia, Ont., to make the big leagues, stands near the banner and plaque announcing that the main diamond at Henning Park on Highway 6 is named in honour of his baseball career and his many years of community service as a sponsor of youth sports. Photo: J.P. Antonacci

August 29, 2019

By J.P. Antonacci

Canadian Baseball Network

Head south from Hamilton, Ont. on Highway 6 towards the sandy beaches of Lake Erie and you’ll pass Henning Park at the corner of Greens Road, near Caledonia. The park is home to six well-used diamonds overseen by the Caledonia Minor Hardball Association. The largest and most prominent of the six, sitting right on the corner of the sprawling property, is named after a fixture in the local sporting scene – Jim Lawrence.

For four decades starting in 1975, there wasn’t a young athlete in Caledonia and the surrounding area who didn’t know Jim and his late wife, Dorothy. The couple ran Lawrence’s Sporting Goods, a busy store on Caledonia’s main drag that outfitted scores of baseball, hockey, and ringette players with uniforms and equipment in the southwestern Ontario farming community, while sponsoring countless teams and community initiatives.

Oh, and Lawrence also happens to be the only Caledonia kid ever to play major league baseball, suiting up for a pair of games with Cleveland in the spring of 1963.

“He’s been around forever in this town. I know he played for Cleveland, but Cleveland’s just a little piece,” said Caledonia Minor Hardball Association president John Uildersma. “If he didn’t play for Cleveland, (the field) would still be there. (His major league career) is just an added bonus.”

It’s a warm summer evening and Lawrence is standing by the fence at Henning Park, near a banner welcoming visitors to Jim Lawrence Field. A plaque next to the banner declares that the diamond was named after Lawrence “in recognition of his dedication and commitment to youth sports of Caledonia.”

“I was really well honoured. John called me and said, ‘Do you mind if we name the ball field after you?’ And I said, ‘Oh, John, that would be great,’” said Lawrence, now 80 years old and looking as hale and hearty as he does on his baseball card – though he freely admits that his days of crouching behind home plate are behind him.

“Don’t ask me to get down there, because I’ll never get back up!” he jokes.

Lawrence’s son Dan said the family was grateful to have their father’s decades of philanthropy and community involvement recognized. But he had a feeling that his dad might turn down the honour.

“That’s just the way he is,” Dan said, describing how Lawrence politely agreed to lend his name to the field when Uildersma told him the news.

“But sure enough, next day I get a phone call – ‘well, you know, I think there’s some other people more deserving than me,’” Dan said, quoting his father.

“We couldn’t think of anyone!” Uildersma said excitedly. “One of the guys on the executive said, ‘I remember when Jimmy would get new bats in, he’d run them out for us to test them. ‘Here, boys, try these bats.’ Nobody else would do that.”

Lawrence’s extended family flocked to Caledonia in June to see the park named in Jim’s honour.

“When I got out here and saw this, it was just amazing, and I’m so honoured. I wish my wife could have been here with me,” Lawrence said.

In the crowd was his 16-year-old grandson, MacGregor, who pitches for the Port Dover Clippers.

“Kids will have that for years to come,” Lawrence said. “I said to MacGregor that night, ‘It would be just great if you got to play ball on Grandpa’s field.”

***

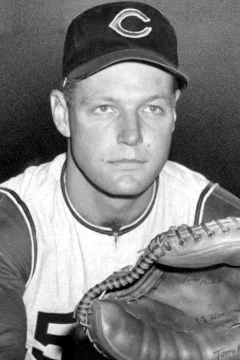

Former catcher Jim Lawrence is the only major league baseball player ever to come out of the farm fields of Caledonia, Ont. Photo: J.P. Antonacci

Lawrence was about his grandson’s age when he convinced his older brother to let him tag along to watch a professional tryout Cleveland was holding at a high school in the nearby farming town of Tillsonburg.

“Thank goodness I took my catcher’s glove,” said Lawrence, who jumped in when one side of the intersquad game was short a catcher.

“Well, I put on quite a show,” he said with a smile.

The teenager pulled a few balls over the right-field fence, which was enough for Cleveland’s scouts.

“The game went on for about an hour and fifteen minutes, and they said, that’s it, everybody can go home except you,” Lawrence said.

The scouts spoke with him for over an hour, laying out their plan for the power-hitting youngster.

“They scouted me for another two years, because they couldn’t sign me until I was in Grade 12,” said Lawrence. In the meantime, he continued to play Little League in Caledonia while getting a taste of stiffer competition with the Hamilton Junior Cardinals – and loving every minute of it.

“I could play baseball from eight in the morning till midnight,” he said. “I just loved it.”

Cleveland’s interest put an end to Lawrence’s hockey career, despite Caledonia having a good midget team for which Lawrence had logged a lot of minutes on the blue line.

“I was a pretty good hockey player, but as soon as Cleveland scouted me, my mother wouldn’t let me play hockey anymore,” he said. “I remember the coach and the assistant coach came to our door at night, and they said, ‘Mrs. Lawrence, let him play.’ And I said, ‘Let me play.’ But she said no.”

Lawrence said his parents, Jean and Tom, supported his dream of playing baseball professionally, even letting his training take precedence over farm chores.

“My parents were really good,” he said. “There was work to be done, because we had business to take cabbage and lettuce and that to a Hamilton wholesaler. We’d be working away and Mom would say, ‘Jim, get in here and have something to eat. There’s a ballgame.’ And I’d say, ‘But Mom, there’s more work to do.’ And she’d say, ‘Get over there and play ball.’”

There was another point on which Jean Lawrence would not budge – her son had to get an education.

“My mother had it in my contract that I had to graduate from Grade 13 before I could go play,” said Lawrence, who remembers being less than impressed with that stipulation.

Perhaps distracted by thoughts of playing against his beloved New York Yankees, Lawrence failed out of school anyway – “I never did graduate Grade 13,” he said – and was signed to a minor league free agent contract with Cleveland in 1958.

***

The Spalding catcher’s mitt that Lawrence received when he joined Cleveland’s Class D affiliate in Cocoa, Florida and a baseball card that depicts him with the Cleveland Indians. Photo: J.P. Antonacci

Playing in the major leagues was still a distant dream when Lawrence first put on the uniform of the Class D Cocoa Indians in the spring of 1958.

But the new glove was real.

“When the scout sent me this, I thought I’d died and gone to heaven,” Lawrence said, his left hand tucked inside the weathered Spalding catcher’s mitt he used while working his way up the minor league ladder.

“The way they play there now, with those flitters they’re throwing, you’ve got to have a big glove with a big web,” he laughed.

Lawrence remembers representatives from the major sporting goods companies approaching rookies at spring training with what sounded like great deals.

“These salesmen came around and said, ‘If you sign with Spalding, we’ll give you a glove and two pair of spikes free for the year, and you can either have a complete set of golf clubs or a hundred bucks.’ Well, I was making 64 dollars every two weeks, so I said ‘I’ll take the hundred bucks,’” Lawrence said.

“The only one who ever turned it down was (Cleveland pitcher) Herb Score. He wouldn’t sign with any of them. And about three years later he signed a contract for $10,000 with either Rawlings or Spalding. That was huge money back then. Now, when you think of the money these companies have made off selling bats and gloves and spikes.”

Along with the new glove, Lawrence received a pair of spikes made of kangaroo leather that fit better than any shoes he’d ever worn.

“You got them a little tight, and then you sat in a bucket of water with them and they’d just mould right around your feet,” he said.

But pro baseball wasn’t just new toys and the allure of making real money, however modest those early paycheques were. Lawrence found it tough to adjust mentally, and he wondered if the life of an athlete really was for him.

“The first year when I went down, I got homesick, so I bought a plane ticket to go home. I had visions of being a minister. The farm director said, ‘Okay, you go home and be a minister,’” he said.

“So I called my mom and said, ‘I’m coming home.’ And she said, ‘You can’t do that. Your dad just bought a brand new car to go see you play ball. You can’t come home – your dad could barely afford that car.’

“So I went back and said, ‘I’m staying.’ It was that close.”

***

Lawrence said his minor league debut was a day he’ll never forget.

“My best honour was signing a big league contract, but my biggest thrill was playing my first professional ballgame in Cocoa, Florida,” he said.

“I was a little nervous my first game, but after that it was just another game of ball.”

He made a good first impression on the organization, batting .277 in 136 games with Cocoa, walloping 12 home runs and driving in 73 while drawing 56 walks.

Playing in the southern United States also made quite the impression on the farm kid who’d never left rural Ontario.

“What you see, it flabbergasted me, it really did. I saw a lot of things down there, under the Mason-Dixon Line, that I never thought existed,” said Lawrence, describing segregated bleachers and other shocking facts of life under Jim Crow.

“It just opened my eyes to how the black population was treated down there then,” he said.

With a month left in the season, Lawrence’s solid play earned him a promotion to Minot, North Dakota, where he played the following year as a teammate of fellow catcher Ted Baker from Brantford, Ont.

At Class-A Reading, he formed a battery with Canadian Baseball Hall of Famer Ron Taylor of Toronto. Taylor was one player Cleveland let get away, Lawrence said.

“Ron went to St. Louis and won a World Series, went to the Mets and won a World Series – but he wasn’t good enough to pitch for Cleveland,” he laughed.

Lawrence was proud to tell his American teammates where he was from, even if they weren’t exactly up to speed on Canadian life.

“They had no idea about Canada. They’d say, ‘You must get snow most of the year up there,’” he chuckled. “I’d say, ‘We’re just close to Detroit and Buffalo. We get the same weather you do.’”

The power-hitting catcher put up decent numbers over his six-year stint in the minors, which included stops in Salt Lake City, Charleston and Jacksonville.

“I never hit for very high average – in the .250, .260 range – but I could really run and I hit a lot of singles, doubles,” he said.

Through all the long bus rides on the back roads of America, Lawrence always believed that one day he’d make it to the major leagues.

“That was the urge, that I just thought I would,” he said. “I loved to play baseball. I just loved it. And I kept being promoted. The farm director, Hoot Evers at the time, thought I was great and kept moving me up. And I was doing okay.”

He was doing so well that on May 27, 1963, Lawrence got the call he’d long dreamed of – he was headed to the majors.

Lawrence was called up to big leagues on May 27, 1963.

Three days later he suited up for Cleveland in an 8-4 win against the Chicago White Sox at Comiskey Park, getting into the game as a defensive replacement after starting catcher Joe Azcue was lifted for a pinch hitter.

“Oh, it was something,” Lawrence said of how it felt to put on his jersey and cap emblazoned with the distinctive capital C.

“In fact, Hoot Evers called me and said, ‘Take a couple aspirin before you go on the field, because you’re gonna be nervous.’ And I was.”

Lawrence next got into a game on June 1, again subbing in for Azcue in the ninth inning of a home game against his childhood favourite team, the New York Yankees.

The next thing he knew, the great Mickey Mantle stepped into the batter’s box.

“Mickey Mantle was my idol growing up. I used to run home to get the Yankees game on the radio, and hopefully I could catch the last few innings,” Lawrence said.

To then be crouching a few feet from the Mick was heady stuff for a 24-year-old from Caledonia.

“It was quite an experience,” said Lawrence, whose father and other relatives and friends made it to Cleveland to see him live out a dream that had started on a sandlot in Tillsonburg.

“It was great,” Lawrence said. “They loved it.”

The official record shows that Lawrence made three putouts and committed one error over his three innings in the majors. He also allowed a baserunner to steal third – but there’s a story there.

With his Yankees counterpart, catcher Elston Howard, at the plate, Jack Reed – sent in as a pinch runner for Roger Maris, who was two seasons removed from hitting 61 home runs – took off for third.

“Howard didn’t get out of the way and I had to throw the ball over him, and it was high,” Lawrence recalled.

“And I said to him, ‘You know, if I was here a couple more years, I would’ve hit you in the head with it.’ And he said, ‘If you were here for a couple more years, I’d get out of the way.’”

But Lawrence’s career did not last a couple more years. He was soon sent back down to Triple-A Jacksonville with some incredible memories – and one lifelong regret.

“Never got to start a game. And I never got to hit,” he said. “Once it was my turn to come up to bat, and (Cleveland manager) Birdie Tebbetts pinch hit for me.”

***

He would never again make it that close to testing his mettle against the best pitchers in the world. Lawrence finished the season in the minors, and the following year registered just one at-bat for Triple-A Portland, lining a single in what would be his final professional game.

His career ended after he tore his rotator cuff, a death knell in the days before MRIs and arthroscopic surgery.

“And then that was it. I knew I couldn’t go any further,” Lawrence said. “If you can’t throw, you can’t catch.”

He returned to Caledonia, needing to start a new career. His wife, Dorothy, went back to nursing school, while Jim became a salesman for Brewer’s Retail. He didn’t love that work after a few years, so when he was offered the opportunity to open a sporting goods store, he and Dorothy decided to jump at it.

“So my wife quit nursing and her and I started the sporting goods business,” Lawrence said. “We worked long hours as well as raising two kids (Dan and Julie Ann).”

The store was a local institution for decades, with the Lawrences logging 60-hour weeks to keep it afloat. As the years passed, it’s likely that some of the kids who got their skates sharpened and uniforms outfitted at Lawrence’s Sporting Goods didn’t realize that the man behind the counter was a former big league catcher. To them, Jim and Dorothy were the friendly couple who helped them pursue their own sporting dreams.

“I loved people. We sponsored a lot of teams, a lot of people,” Lawrence said. “The only thing we couldn’t do was volunteer, because we were working such long hours at the store.”

Lawrence did the bookkeeping, and he said he and Dorothy ran things harmoniously for all those years.

“Everybody would say, ‘how can you and your wife work together?’ It was easy. My wife looked after the clothing part, I did all the skate sharpening and all that sort of stuff. So we’d go home and sit down for supper, and I’d say, ‘So what did you do today?’ And she would tell me, and I’d tell her. So that’s how we got along for so long,” he said with a laugh.

***

Dan Lawrence was born the year after his father retired from professional baseball. The elder Lawrence wasn’t one to brag about his achievements or be protective of his mementos.

“He’d hardly ever talk about it,” Dan said. “He was so humble.”

So Dan used his dad’s old bats until they broke in action, and lost all the baseballs Lawrence brought back from his playing days. Dan remembers rooting around in his dad’s equipment bag before settling in to watch the Saturday afternoon game of the week on TV.

“I’d dress up in his old catcher’s gear and watch the ballgame. And then go play road hockey,” he said.

The one thing that frustrated Dan was that his dad would only occasionally agree to play catch with him.

“And then I’d find out through Mom that he couldn’t move his arm for a week, literally, because his rotator cuff was torn,” he said.

It wasn’t until major league baseball came to Canada that Dan truly got a sense of the elite fraternity to which his father belonged. The family was on one of their frequent trips to Toronto, and while Dorothy and Julie Ann explored Ontario Place, Jim and Dan went to Exhibition Stadium to watch the Blue Jays take batting practice. Jim spotted pitcher Steve Hargan, his former minor league teammate, warming up in the Toronto bullpen.

“Dad yelled down, ‘Hargan!’ He looks up and goes, ‘Jimmy!’” recalled Dan, who was about 12 at the time.

The former farmhands reunited after more than a decade, swapping baseball stories as a crowd of fans gathered to listen and get autographs.

“That’s when it really hit me just at what level he played,” Dan said.

Lawrence remains an avid baseball fan, and even though he played for Cleveland, the Yankees are still his team.

“And I’ll tell you why – no long hair, no beards,” he said. “I’m old school. When I played, there was no long hair, no beards. But it’s a different time now.”

The athletes themselves are different too, he added.

“They’re bigger, they’re stronger, they’re faster,” he said. “When I played, the season was over, you did whatever you were going to do, and you showed up in spring training to get in shape. Now the ballplayers maybe take it easy for a month and then they’re right back in the gyms.

“When I played, I was a big catcher,” said Lawrence, who checked in at six-foot-one, 185 pounds. “Now it’s hard to find a catcher under six feet. They’re all six-two, six-three, six-four. Big. And everybody can run now. We didn’t have that many players who could really run.”

He noted how many more opportunities exist for Canadian players to showcase their skills today, and as a result, how many more Canadians are playing ball south of the border.

“There were only three Canadians down there (in the minor leagues) when I went, and now there’s a thousand and some down there,” he said.

***

Fans of the film Field of Dreams might see a little of Moonlight Graham in Lawrence’s story. Graham was immortalized in W.P. Kinsella’s classic tale as the ballplayer who made one appearance in the major leagues and never got to bat.

But while Lawrence may have a gripe with the baseball gods for denying him the chance to hit, the finest ballplayer Caledonia ever produced lights up when talking about his brief moment at the pinnacle of the sport.

“It’s not much,” he said, smiling.

“But I was there.”