Mark Whicker: New rules will mean more stolen bases but with an asterisk

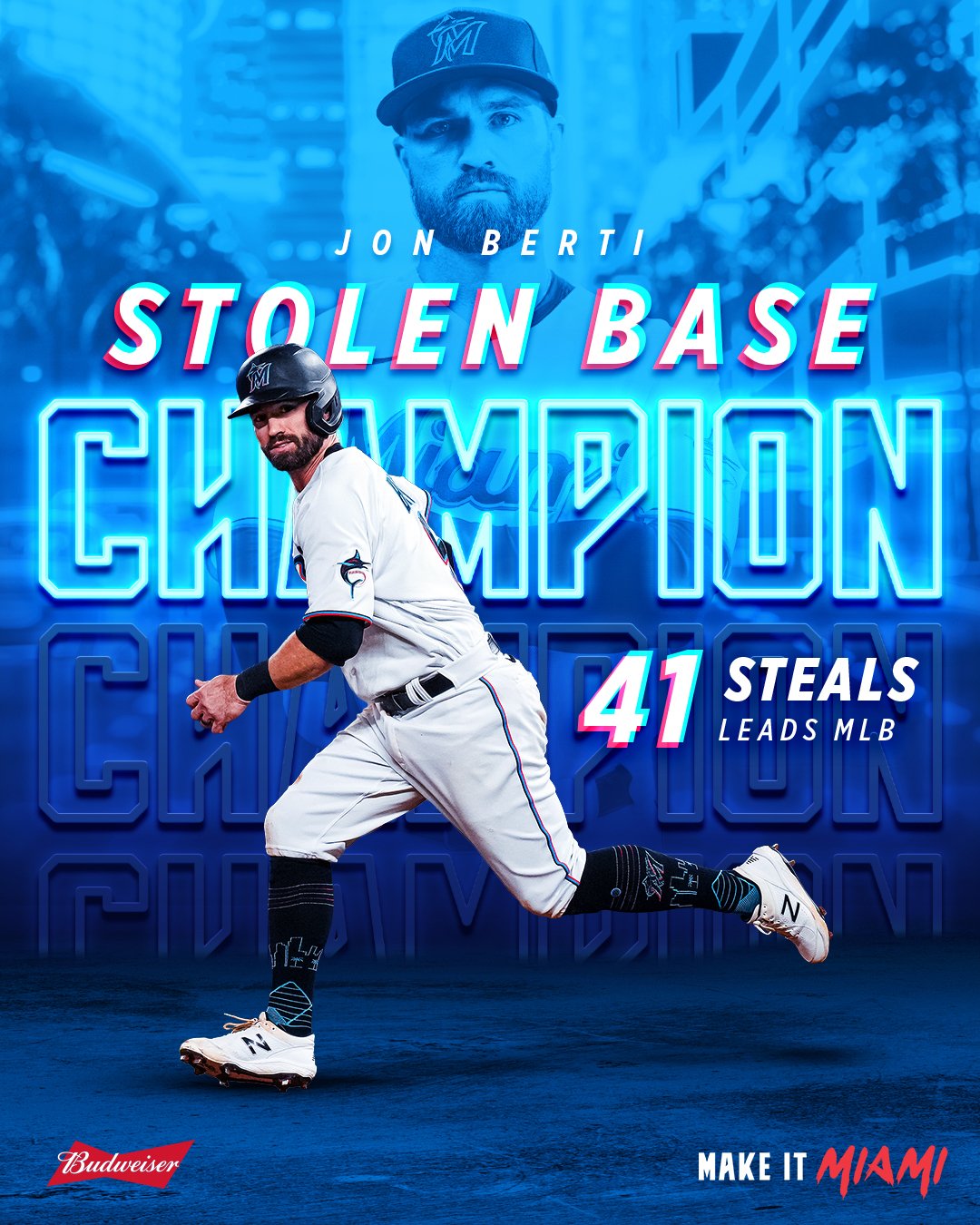

Miami Marlins utility player Jon Berti led the major leagues with 41 stolen bases in 2022. Photo: Miami Marlins/Twitter

March 16, 2023

By Mark Whicker

Canadian Baseball Network

The stolen base will return to baseball this season. It’s almost unavoidable.

Pitchers are restricted to two pickoff throws. A third one, if unsuccessful, will be ruled a balk. The actual bases are wide. A basestealer can look at the pitch clock, instituted and enforced this coming season, and time his dash perfectly with the countdown.

The minor leagues tried this rule in 2022 and its teams produced 1.1 steals per game, which almost matched the number of steal attempts the previous season.

But those who have decried the base-to-base calcification of the game are not as happy as they thought they’d be.The steals aren’t rising because of some organic process, or because today’s Rickey Hendersons and Lou Brocks have been lured off the gridiron and court and back onto the diamond, or because a wise man like Davey Lopes is teaching the subtleties.

There is no art to this. It’s just a force-fed consequence of other changes that have sprung from the Manfred Mann era. A game that has largely disdained asterisks is about to wear a big one. One cannot imagine these are popular changes in Philadelphia, where pitcher Aaron Nola and catcher J.T. Realmuto crafted ways to stop whatever running game there was. Basestealers were 11 for 19 against Nola. That’s the lowest percentage against any major league pitchers who gave up 10 steals. Milwaukee’s Corbin Burnes suffered only five successful steals in nine attempts.

Realmuto had 27 assists during steal attempts, nine more than any other MLB catcher, and the Phillies led baseball by catching 40 percent of stealers. Realmuto’s percentage was 44 percent. (Although it would be interesting to see Aaron Nola pitch to his brother Austin, who is with the Padres. Austin’s presence behind the plate was like a starter’s pistol. Stealers were successful 56 times in 64 attempts against him.)

Is it fair to remove all that skill, preparation and deception from the Nola-Realmuto tandem? Of course not. Slide-stepping, stepping off, varying the tempo, all of that is part of the baseball mindgame. When the stealer knows precisely when he can go, that’s almost like stealing signs. Yet everything in baseball is suddenly judged by time elapsed. What’s the hurry?

It’s reminiscent of Tom Hammonds, the Georgia Tech basketball player who loved rural pursuits like hunting and fishing. He once told his coach, the New York-bred Bobby Cremins, that they should go fishing together sometime.

“Great,” Cremins replied. “But how long does it take?”

Sure, the extraneous time should be sliced from the game. If MLB just accomplishes half of what the minor leagues did along those lines in 2022, that would be extraordinary. But that was done without messing with the actual tenets of play. If Henderson had known he could take off after three pickoff throws, he might have stolen 200 bases in a season (his career high was 130).

It’s hypocritical to insist on long TV commercial breaks between innings and then complain about the length of the games themselves. It’s never been about time of game, per se. It’s about action within that time. Game 7 of the 2016 World Series, in which the Cubs beat Cleveland, and Game 6 of the 2011 World Series, in which the Cardinals kept coming back to beat the Rangers and force a Game 7 that they won, were two of the most gripping nights in baseball history. Cubs-Cleveland lasted 4:28, Cardinals-Rangers lasted 4:33. No one complained, or cared.

And steals are a crucial part of that action, that energy. When Whitey Herzog’s Cardinals came to town in the 80s, fans were perched on the edge, and opponents tried to fight off the dread. In 1985, Vince Coleman stole 110 bases but four other Cardinals stole 30 or more, and they swiped 314 bases and were caught 96 times. That team, which lost the World Series in seven games to Kansas City, was next-to-last in National League home runs, but scored 41 more runs than anyone else. But they weren’t alone. Eight N.L. teams stole over 100 bases in 1985. Last year, only four did.

In 1987, major league teams stole 0.85 bases per game. Beginning in 2020, that remains the highest figure ever.

You may know who Jon Berti is. More likely, you don’t. If you stopped 15 people on Yonge Street, you’ll be lucky to find someone who does. Berti plays for Miami and was the only major leaguer to steal more than 40 last year. Even in 2007 there were six who stole more than 50, led by Jose Reyes and his 78.

People remember Cincinnati’s Big Red Machine for big muscles and clusters of home runs. In 1976, Joe Morgan had 60 steals, Ken Griffey Sr. had 34, Cesar Geronimo had 22 and Dave Concepcion 21. One night at Riverfront Stadium the Reds went on such a rampage against the Dodgers that official scorer (and Cincinnati Enquirer beat writer) Bob Hertzel got tired of announcing “stolen base” in the press box and began announcing, “burglarized base,” “pilfered pillow” and “copped canvas.”

Back then, you didn’t look at the steal as an unwise risk of making an out, as the modernists do, or a foolish way to remove the bat from someone who might swing for the fences. It wasn’t the actual steal but the threat of it that was such a disruption, and any pitcher would agree. Anything that got the defense moving was considered a plus.

With that, the steal was making a faint comeback anyway. There were 0.57 steals, per team per game, in 2022, the most in four seasons. And the rate of catching basestealers has atrophied, considering the emphasis on catcher “pop” times. The four lowest caught-stealing rates of all time have been in the past four years. It was 0.15 last year.

All of those fluctuations happened because of adjustments, because Maury Wills found a way to hoist himself out of a minor-league life sentence and take a malnourished Dodger offense to championships, because the Cardinals believed in Yadier Molina’s ability to catch and throw and teach the pitchers to hold ‘em close, Now the next wave of basestealing will come from a page in the rulebook. You don’t lament this lapse of judgment, from a boardroom full of suits, as much as you shudder over what’s next..