Munro: A look at all-time Canadian pitching statistics

With seven starts with the New York Yankees this season, left-hander James Paxton (Delta, B.C.) will pass Rheal Cormier (Cap-Pele, N.B.) and move into 11th place among Canadian pitchers in major league starts. Photo: New York Yankees/Twitter

By Neil Munro

Canadian Baseball Network

Career Pitching Milestones for Canadian Ball Players at Start of 2019

As we get ready for the start of the 2019 baseball season, we can take a look at the prospects for several Canadian pitchers to move up significantly on the lists of career statistical totals in many different categories.

A few Canadian starting pitchers who saw extensive action in the big leagues last season are sure to still hold down roster spots this year. These pitchers include James Paxton (Delta, B.C.) and Nick Pivetta (Victoria, B.C.). Pivetta held down a regular spot in the Phillies’ starting rotation and has continued to progress to the point where he might become one of the premier starting pitchers in the league. Paxton can now be considered one of the best starting pitchers in the American League. If not for the fact that he had multiple stints on the DL in each of his last two seasons, he may have been in contention as a candidate for the Cy Young Award. He has been picked up by the Yankees for the 2019 season and could very well end up being the ace of their staff. With their explosive slugging lineup backing him up, Paxton should have his most impressive campaign to date. He is just starting to move up on the list of career statistical leaders among Canadian hurlers, as the following table attest.

Before we take a closer look at the career pitching leaders, it is worth reviewing the way in which a number of statistical categories have changed significantly historically, and also make a count of the number of Canadians with major league experience over time, which have accumulated the figures in the tables which follow. In all, there have been some 252 Canadian born players who have appeared in at least one game in the major leagues since 1876. As discussed previously in the article dealing with the batting milestones, this number is augmented additional players with dual Canadian-American citizenship who were born outside of this country. Some of these players moved to Canada from Europe at a very young age and developed their batting skills while living in Canada. More recently, some were born in the USA as their Canadian fathers played professional hockey south of the border. These players will soon be joined by players born in Canada who have reversed the previous trend in that their foreign-born fathers lived in Toronto while playing for the Blue Jays (or for the Expos in the case of Vladimir Guerrero Jr.).

There are just two such pitchers who have had a significant number of major league innings pitched. These two are Jameson Taillon and Chris Reitsma. Reitsma was primarily a relief pitcher with seven years of major league experience. He pitched for three different ball clubs accumulating 338 major league appearances (and another 7 games pitched in the post-season). Taillon has progressed so significantly during his three seasons of big league pitching in that he can now be considered as one of the top 15 or 20 starting pitchers in the National League. Barring a serious injury, he should post well over 100 career big league victories before he hangs up his spikes.

In many specific statistical pitching categories, the typical numbers accumulated by regular big league performers have also changed significantly over the last 140 years. In the first twenty years of major league action, many pitchers would routinely pitch well over 500 innings per season, with some even completing as many as 70 of games that they started. We can likely predict that no pitcher will start more than 35 games in 2014 and we can assert with absolute certainty that no pitcher will complete as many as ten games this year. The number of strikeouts and walks accumulated by all pitchers (and by batters) has gone up and down noticeably over time, and for strikeouts in particular, the frequency is at unprecedented high levels in recent years. However, the most striking difference in major league pitching stats over the first 140 years of major league history has been the use of relief pitchers.

Today, most All-Star starting pitchers will not record a single shutout in the entire season while several fringe players would often garner two or three shutouts per year while just seeing limited action in baseball’s first sixty or seventy seasons of play. In 2018, all of the National League pitchers combined to post a mere 17 complete games pitched (two by Taillon as the co-leader in that category). In contrast, Fergie Jenkins (Chatham, Ont.) had eight different campaigns in which he had 20 or more complete games pitched. Bob Emslie (St. Thomas, Ont.) completed every one of his 50 starting assignments in 1884 and just managed to be the ninth ranked pitcher in complete games that year. Pitching saves were not officially recorded until the 1960s and holds were not counted (for the set-up hurlers from the bullpen) until the 1990s. Using box scores from a number of different sources, I have added to the official totals in these categories in compiling my lists of career leaders. Paul Quantrill (Port Hope, Ont.) was one of the pioneers in accumulating significant totals in the category of pitching “holds’. He led his league twice in that category and currently has the eleventh most career hold among all major league hurlers.

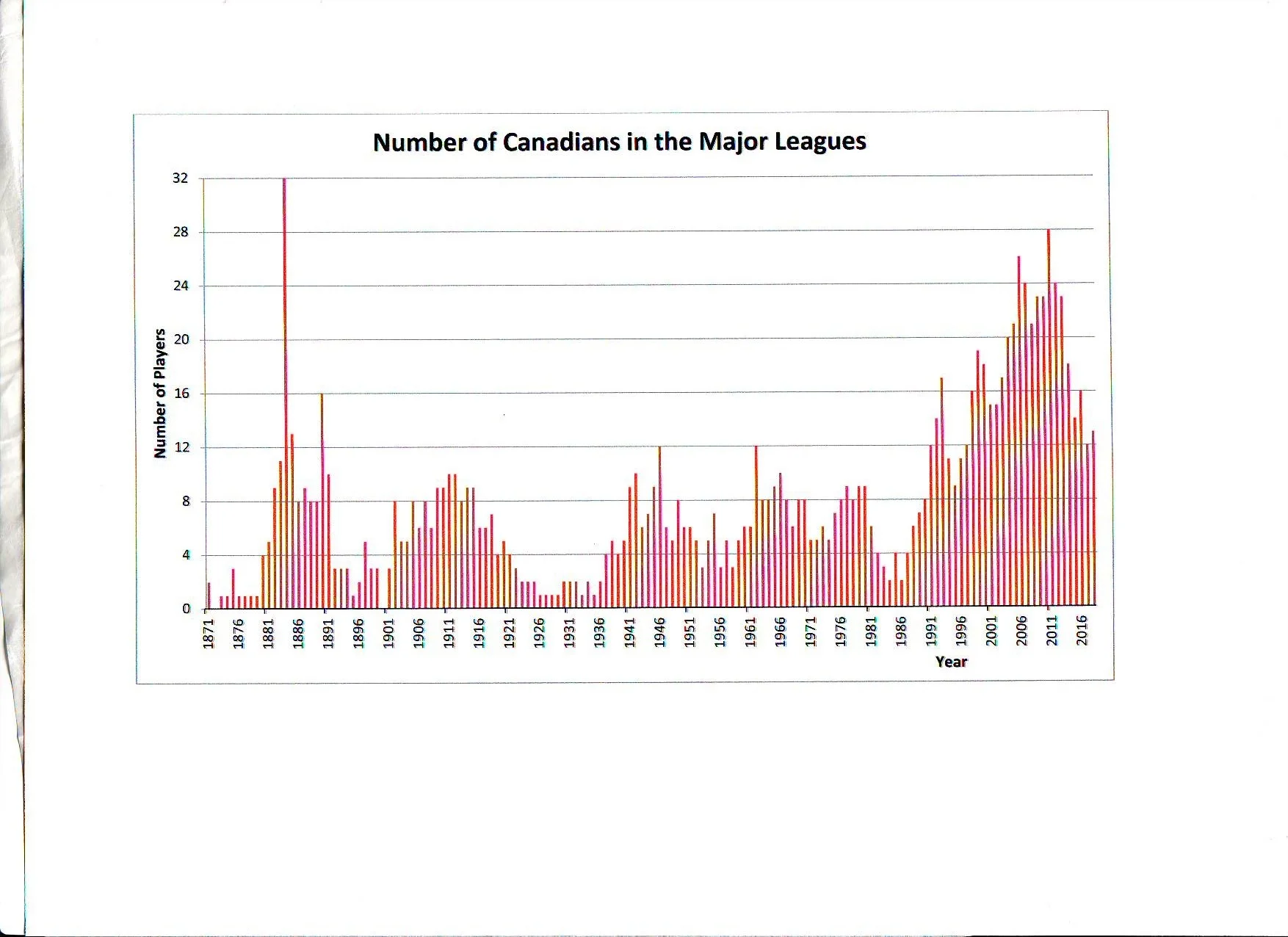

As outlined earlier in the batting milestones, the distribution of Canadians who played in the big leagues has changed dramatically in the last 140 years. One reason for this is the fact that the number of major league franchises in existence at any particular point in time has also varied considerably. In the 1900 season, there were just eight teams taking part in major league play (in the National League). On the other hand, in 1884, there were 33 ball clubs challenging for championships in three different leagues (the NL, the American Association and the Union Association) although it certainly requires a stretch of the imagination to label several of these teams (a few who did not even complete their schedule of games) as being anything resembling “major league” caliber. As a result, Canada did not have a single player on a major league roster in the 1900 season, while no fewer than 32 Canadians appeared in at least one game in 1884. That certainly accounts for most of the pronounced fluctuations displayed in the graph shown below. However, there are still significant dips and peaks in the numbers of Canadian major league players over time, even as the number of teams remained consistent over long time frames. We can likely expect to see about ten to fifteen Canadians making an appearance on a big league roster some time during the 2019 season.

Here then are the targets and milestones that our current crop of Canadian ball players can shoot for in 2018 and in the next few seasons. In most instances, I have ranked the top 15 in each category, but in a few limited cases I have just listed the top 10 when differences in the recording of statistics or in managerial strategies employed dictate that the leaders would amass very diminutive career totals. As indicated earlier, the differences over time in most pitching categories are even more pronounced than is the case for batting comparisons. This is primarily as a result of the workload assumed by starting and relief pitchers (down somewhat in recent decades, and substantially up for starting pitchers from the 19th century) and also because of some managerial strategies employed (five starters as opposed to three or four, and a bullpen which routinely sees several relief pitchers used in a single game instead relying on one dependable ace (as was the case in the 1950s and 1960s).

We will begin with the top 15 workhorses, in terms of pitching appearances, for games started, innings pitched and batters faced. You do not have to even glance at the following lists of pitching leaders, to deduce that Ferguson Jenkins is the runaway leader in virtually all categories, save for those of the relief specialists of more recent vintage. John Axford (Port Dover, Ont.) was quite successful in middle relief while pitching for the Blue Jays in 2018, but saw only very limited service with the Dodgers after he was traded in mid-season. Hopefully he can catch on with some major league team and continue moving up on the tables of relief pitching categories in 2019. James Paxton has been traded to the Yankees for 2019 and should have an opportunity to rack up significant totals for wins and strikeouts with that powerhouse batting lineup behind him. He may even wind up being the ace of the staff this year. He is just beginning to appear on some pitching categories presented below.

Next we view the leaders in productivity – the top hurlers in posting career wins, losses, saves and shutouts. As mentioned previously, the category of saves is almost completely lacking in pitchers working before 1960, while the shutout category has practically no one from the recent decades. With Jeff Francis (North Delta, B.C.) and Erik Bedard (Navan, Ont.) now retired, and most current Canadian stars pitching in relief, it looks like it will be a very long time before we see another Canuck hurler with 100 or more victories.

Next we look at the flamethrowers and the wild men (who can often be both at the same time). The best at fanning opposing hitters and the pitchers who were most generous in giving up free passes are shown now. Before Ryan Dempster (Gibsons, B.C.) decided to sit out the 2014 season, he had actually passed Ferguson Jenkins in career walks issued. While this may seem to be a dubious honour, a pitcher still has to display some degree of success over a long period of time to ever yield more than 1000 walks. It may seem that Phil Marchildon (Penetanguishene, Ont.) and Dick Fowler (Toronto, Ont.) issued a great number of complimentary passes for these quite successful pitchers, but the number of walks surrendered in the 1946-1956 period (especially in the American League) remains unapproached in frequency, either before or after that time period.

Next come four categories in which pitchers gave up hits, runs and homers to opposing batters. Again, the frequency of home runs surrendered in the years before 1920 was very low compared to the period after 1950, and particularly since 1990. As a rule, pitchers who give up a high number of home runs generally have a low frequency of issuing walks. Jeff Francis spent most of his career pitching for the Colorado Rockies in a ball park famous for batters eager to blast out high numbers of home runs.

The final categories in which I list the top 15 leaders are in games finished and earned run average. ERA might seem to be the most important pitching category of them all, but it is highly sensitive to the ball park in which a pitcher spends most of his time working and it also varies dramatically between different eras. Between 1900 and 1920, more than 30 percent of the runs given up by pitchers were unearned, mostly as a result of the high number of errors in the field, but also because of the poor condition of the playing surface itself. Prior to 1890, more than half of the runs given up were usually of the unearned type. In recent years over 90 percent of the runs allowed are of the earned variety. A pitcher between 1901 and 1919 posting an ERA consistently above 3.00 was destined for demotion to the minor leagues in short order, while since 1920, some ERA titles have actually been won with marks above the 3.00 level.

Once again, the question of a minimum number of innings pitched for qualifying on the ERA list comes into play. I have arbitrarily opted for a 500 IP minimum to be attained in order to rank on the list of our top 15. The category of games finished is included here because it pays homage to relief specialists who usually do not make the top levels of career leaders in other categories requiring a high number of innings pitched to move up in lifetime ranking. As a result of this minimum workload level, the following pitchers do not appear in the table of ERA leaders: Rube Vickers (2.93), Bob Steele (3.05), Win Kellum (3.19), Jeff Zimmerman (3.27), John Axford (3.29), Ed Bahr (3.37), Clarence Currie (3.39 and Tip O’Neill (3.39). You can see that most of these hurlers pitched in the dead ball era or are relief specialists with very few career innings accumulated to date. Yes, that Tip O’Neill (Woodstock, Ont.) is the same noted slugger appearing on most of the lists of top hitters seen above, and he is still Canada’s lone batter with a .400 season average under his belt. He began his career as a pitcher for two years before his worth as a dangerous slugger was clearly understood by management. Axford moved into second place in the category of games finished in 2018 and he and Paxton are now in the top 15 in earned run average in that both have now surpassed the 500 IP level.

We complete our lists of pitching performances with some top 10 rankings in categories rarely seen in most publications. These include holds for the set-up relief pitchers coming into a contest before the ball is handed to the closer for the last inning of work. In addition, batters hit by a pitch, wild pitches and intentional bases on balls permitted are shown in the charts following. As outlined in the batting section, instances of batters hit by a pitch were not recorded before 1884 in the American Association and not before 1887 in the National League. Before then, an unlucky combatant was simply expected to tough it out and stand in at the plate for the next pitch, after being plunked. Intentional walks first appeared in the official records in 1955, but research has uncovered quite a bit of the IBB data for years between 1940 and 1954. Where it is available, the IBB figures given below include this additional data. Surprisingly, the number of IBB issued by NL pitchers is almost always significantly higher than are the figures for their AL counterparts. This was true even before the time when the DH was adopted by the Junior Circuit. As a rule, relief pitchers allow intentional walks with a far greater frequency than do starting pitchers. They are usually the league leader in this category even though they pitch only a small fraction of the number of innings that the starters compile. The number of wild pitches recorded in the nineteenth century dwarfs the number given up today, even for the most erratic of the current crop of pitchers in the majors. Keep this in mind when you see the figures presented for WP given below. As well, the official scorers from the first forty years of major league baseball differed greatly in the manner in which they designated an errant throw, either to be recorded as a passed ball or a wild pitch. They were often biased in favour of a local star pitcher or catcher in making a decision.

There you have it – the best career performances by our Canadian baseball pitchers. Some of the current collection of stars is certain to move up gradually in several of the categories listed above. Perhaps some of them will eventually rise right up to the very top in a few instances.