Munro predicts that Walker will be elected to Hall in 2020

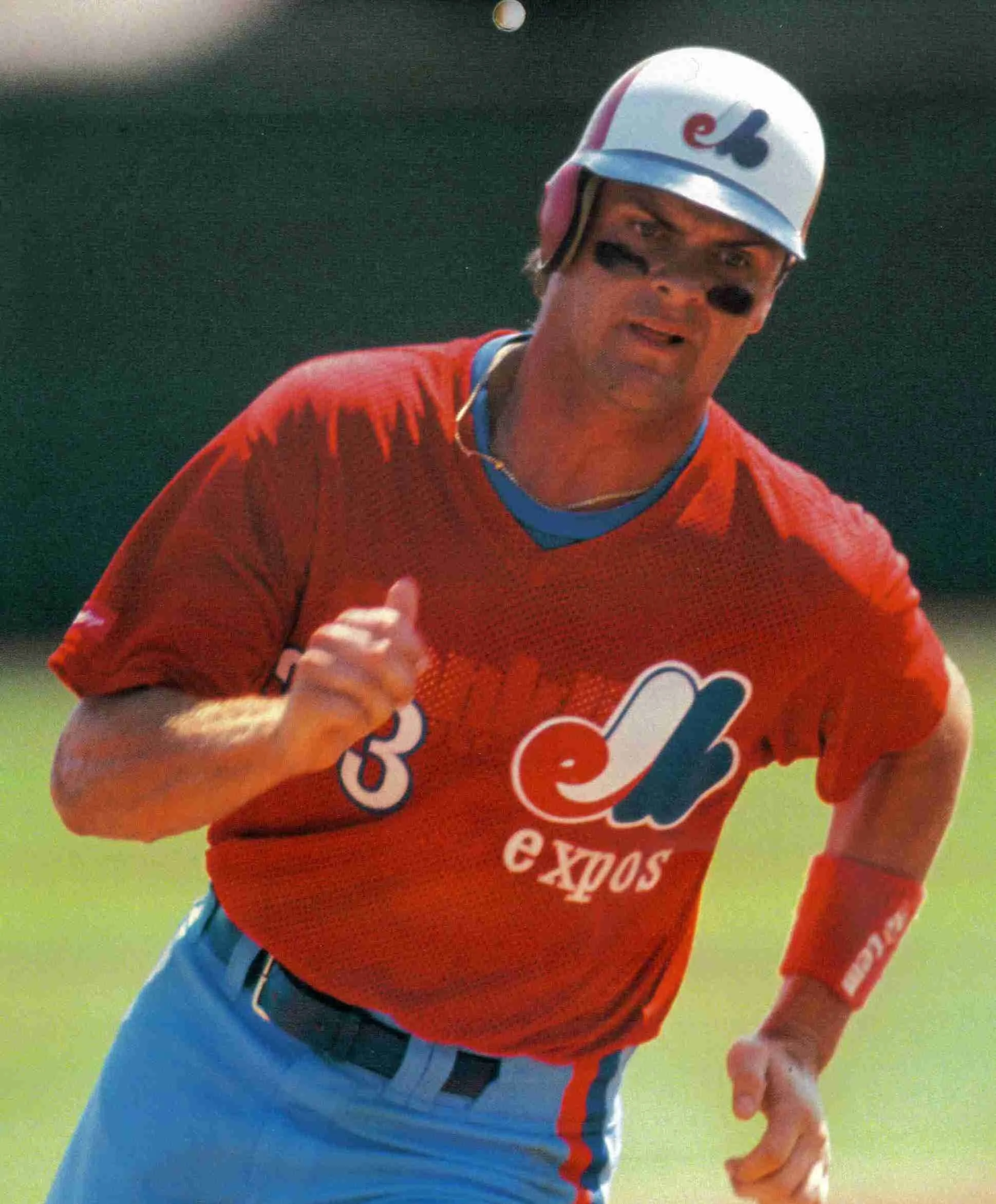

This is Maple Ridge, B.C., native Larry Walker’s last year on the baseball writers’ National Baseball Hall of Fame ballot. Photo: Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame

November 18, 2019

By Neil Munro

Canadian Baseball Network

Larry Walker retired as an active player following the 2005 baseball season, so his name has appeared on nine annual ballots to date (from 2011 through 2018).

His best showing (in terms of the percentage of votes amassed) was on the 2019 ballot, when he received 54.6% of the 425 ballots cast. Although it is certainly not a hard and fast rule, players who have received more than 50% of the votes cast are likely to eventually be inducted into the Hall of Fame, either in subsequent elections or by one of the voting panels (once deemed the veterans’ screening committee) charged with the task of selecting deserving Hall of Fame inductees who had been overlooked in the annual voting process.

Walker has just one more year of eligibility left to appear on an annual Hall of Fame ballot. If he does not receive the required 75% cut-off for election to the Hall of Fame, his fate will rest in the hands of the Hall’s “Today’s Game” voting panel that gives a second look at players who participated in the big leagues since 1988.

The next scheduled year for this committee to meet is 2021 (there are four such committees serving on a rotating basis). For example, two of the 2019 Hall of Fame inductees, Harold Baines and Lee Smith, gained admission to Cooperstown by this committee. The committee will consider 10 deserving candidates in 2021 (no waiting period is required once their names have been dropped from the annual ballot). The rules governing the make-up and timelines for the BBWAA vote and the “Veterans Committee(s)” appear as an appendix at the conclusion of this article.

The knock against Walker being elected to the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown has always been that his batting totals were inflated from having the benefit of playing in the thin air at Colorado for much of his career. Indeed, his on-base percentage (.400, which ranks 55th all-time), his slugging percentage (.565, which ranks 12th all-time) and his OPS (.965, which ranks 15th all-time) place him in some very elite company among baseball’s greatest batters. However, the respective figures for his non-Colorado playing days are .362, .489 and .851. Walker also played 674 games with the Expos and 144 games with the Cardinals during his career. It should be noted that Olympic Stadium in Montreal was a pitchers’ haven and his days in St. Louis were at the tail end of his career when all batters begin to see their productivity drop off.

Actually, I believe that the single factor that hurts Walker’s statistics more than anything else were his frequent injuries which dramatically curtailed many of his most productive season totals. Walker played in more than 150 games in just one season of his career (his MVP campaign of 1997) and reached 500 or more at bats just twice in his career. Furthermore, his best season in Montreal (1994) was cut short by the player strike that wiped out a third of the schedule and all of his likely post-season play.

Larry Walker (Maple Ridge, B.C.) became the first Canadian to win the National League MVP Award when he took home the honour with the Colorado Rockies in 1997.

If Walker had regularly participated in more than 150 games, he almost certainly would have had three more seasons with 40 or more home runs. On the other hand, playing in Coors Field did not inflate Walker’s superb talents in the outfield (seven Gold Glove Awards) or on the base paths (he had 230 stolen bases).

Now let’s put the coming vote for the 2020 Hall of Fame candidates under the microscope. Actually the average number of votes per ballot submitted annually by each member of the BBWAA has changed dramatically during the last few years. For example, in the last six years (for the votes from 2014 through 2019) the average number of names submitted by each voter was 8.23, while the average number in the six-year span prior to 2014 was just 5.68. There are several possible reasons for this change.

On July 26, 2014, the Hall of Fame announced changes to the rules for election of recently retired players, reducing the number of years a player will be eligible to be on the ballot from 15 years to 10. At that time, two candidates on the BBWAA ballot (Lee Smith and Alan Trammell) were grandfathered into this system and retained their previous 15 years of eligibility. In addition, all BBWAA members who were otherwise eligible to cast ballots were required to complete a registration form and sign a code of conduct before receiving their ballots.

The code of conduct specifically states that the ballot is non-transferable, a direct reaction to one BBWAA member turning his 2014 Hall of Fame ballot over to the sports Website Deadspin and allowing the site's readers to make his Hall votes (an act that drew him a lifetime ban from future voting). Violation of the code of conduct will result in a lifetime ban from BBWAA voting. As well, the Hall of Fame committee now makes public the names of all members who cast ballots (but not their individual votes) when it announces the election results.

Recent voting rules changes (announced on July 28, 2015) tightened the qualifications for the BBWAA electorate even further. Beginning with the 2016 election, eligible voters must not only have 10 years of continuous BBWAA membership, but must also be active members, or have held active status within the 10 years prior to the election. A BBWAA member who has not been active for more than 10 years can regain voting status by covering MLB in the year preceding the election. As a result of the new rule, the number of ballots that were cast in 2016 decreased by 109 from the previous year, (from 549 to 440).

Almost all BBWAA voting committee members now make their annual vote selections public. In fact a recent move to make this requirement mandatory was passed overwhelmingly by BBWAA members but was vetoed by the Hall of Fame committee itself. However, the process of making voting preferences public is relatively new (no doubt favoured more so by the BBWAA members who survived the more stringent conditions for maintaining their right to vote).

As recently as the 2010 Hall of Fame vote, five ballots were returned with no names appearing on them. This was a routine event in most years of the vote before 2015. As well, some writers simply wrote in the name of their personal favourite and gave no consideration to more deserving candidates appearing on the ballot. This explains why outstanding players like Willie Mays and Ted Williams were not unanimous selections (garnering just 94.7% and 93.4% respectively). It is thought that BBWAA members today would be too embarrassed to leave off the name of a genuine superstar and obvious deserving Hall of Fame candidate.

Now let’s consider the more difficult task of predicting the actual winners and the new Hall of Fame members on the 2020 ballot. Today there are a great many different Hall of Fame point systems and rating formulas used to predict which candidates will be elected and which will fall short. I am going to primarily use the one employed by the notable American baseball historian, Bill Deane. In his annual Hall of Fame prognostication, Deane considers the previous year’s vote counts and subtracts the ones that cannot carry over to the new year’s totals (as a result of players being elected or dropped from the ballot). He then projects where those newly available votes are likely to be distributed (among returning or new candidates). This assumes that the actual members of the BBWAA who cast votes from year to year remain pretty consistent (which appears to be the case). So let’s review the 2019 voting results.

Last year there were 35 candidates on the 2019 ballot; however, only 24 of these received at least one vote. In all, there were 425 ballots cast, and those contained a total of 3404 votes. Of these, Mariano Rivera, Edgar Matinez, Roy Halladay and Mike Mussina were elected. Mariano Rivera (in his first year of eligibility) was the first unanimous selection (taking all 425 votes), Edgar Martinez (in his last year of eligibility) had 363, Roy Halladay (in his first year of eligibility) also had 363 votes, and Mike Mussina had 326 votes. Five players who received at least one vote, but less than the minimum 5%, will not appear on the 2020 ballot. These players were Michael Young (with 9 votes), Lance Berkman (5 votes), Miguel Tejada (5 votes), Roy Oswalt (4 votes), and Placido Polanco (2 votes). It might also be noted that Canada’s Jason Bay and the Blue Jays Vernon Wells were among those who did not receive even one vote. As well, Fred McGriff (who did get 169 votes) failed to be elected in his tenth and final appearance. This amounts to a total of 1,671 votes to be spread around returning candidates or for the new names that appear on the 2020 ballot (at least according to Deane’s theory).

From that 2019 ballot besides Walker, who should see his vote total increase in his last year of eligibility, Curt Schilling (in his second last year on the ballot) will receive considerable attention after being named on 259 ballots (or 60.9 % of the votes cast). It is extremely rare for a player who has been named on 60% of the ballots to fail to eventually be elected to the Hall of Fame. In addition, Roger Clemens (named on 253 ballots) and Barry Bonds (named on 251 ballots) have seen their support gradually increase in recent years. The feeling is growing now that despite their probable reliance on PED enhancements, they will eventually make the 75% cut-off (each has three years left for consideration). Omar Vizquel was the only other candidate on the 2019 ballot with more than 40% of the votes. He is just in his third year of eligibility in 2020.

These are the new names which will appear on this year’s ballot (passing the scrutiny of the screening committee): Derek Jeter, Bobby Abreu, Jason Giambi, Cliff Lee, Rafael Furcal, Eric Chavez, Josh Beckett, Brian Roberts, Alfonso Soriano, Carlos Pena, and Paul Konerko.

To begin with, Derek Jeter is almost certain to receive recognition on 99 or 100% of the ballots cast, so that will effectively account for the 425 votes given to Mariano Rivera in 2019. However, it is unlikely that the other newcomers for 2020 will garner much support and indeed many may well fall well short of the minimum 5% cut-off. So (again in theory) and that leaves approximately 1100 or 1200 votes to be bestowed upon the other 2019 ballot holdovers.

Assuming Curt Schilling is elected and that Clemens and Bonds see their vote totals rise somewhat, it will be very close for Walker’s chances of success. So it comes down to this: Larry Walker’s 2020 vote total will certainly increase but the question is by how much. On last year’s ballots, there were 193 BBWAA members who did not vote for Walker. He needs to pick up approximately 90 more votes from the writers who did not support him last year to close the gap of the additional 20.4% needed and see the hallowed halls of Cooperstown welcome him next July.

Personally, I will predict that Walker will receive 75% of the votes (with a 3% margin) and be elected to the Hall of Fame this time around. You may be interested to learn that Bill Deane has predicted that Walker will make the 75% cut-off and be elected as well. Canadian supporters will have to wait patiently for another couple of months for the good (?) news.

Appendix: BBWAA and Special Committees Voting for Hall of Fame Selection

Members of the Baseball Writers’ Association of America (BBWAA) vote annually to determine the retired ball players to be elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame. The ballots are distributed in November to active and retired baseball beat-writers who have been BBWAA members for ten years or more. All ballots must be returned by December 31 of each year to be included in the official vote. The results of each annual vote are announced in late January and the induction ceremony usually takes place in July. The year of the vote refers to the year in which the induction actually occurs (in the summer) rather than the year in which the ballots are distributed and returned. Thus, Walker’s last chance rests with the 2020 Hall of Fame vote by the BBWAA.

The ballots simply list the candidates in alphabetical order and voters are instructed to choose up to ten names. In recent years, approximately eight names per ballot have been selected. Only ball players who played in at least ten seasons in the majors are eligible. The player’s active seasons in the majors must be not less than five or more than fifteen years prior to the first year his name appears on a ballot. To be elected for selection to the Baseball Hall of Fame, a candidate must be named on at least 75% of the ballots cast. Any candidate receiving less than 5% of the vote is dropped from future ballots. A screening selection committee actually determines the names of the players that are deemed to be worthy enough to even appear on a ballot in their first year of eligibility.

Throughout history, the Commissioner of Baseball has appointed several special committees for another look at certain groups of players. The Hall has also issued special mandates and modified the rules for certain groups of players. For example, in the late 1990s, the old Veterans Committee was to elect one Negro League player and one 19th century player each year.

On July 23, 2016, the Hall of Fame announced changes to the committee system, which had originally been established in 2010. The system's timeframes were restructured to place a greater emphasis on the modern game, and to reduce the frequency at which individuals from the pre-1970 game (including Negro Leagues figures) will have their careers reviewed.

Separate 16-member subcommittees continue to vote on individuals from different eras of baseball, with candidates still being classified by the time periods that cover their greatest contributions:

Early Baseball (1871–1949)

Golden Days (1950–1969)

Modern Baseball (1970–1987)

Today's Game (1988 and later)

All committees' ballots include 10 candidates. At least one committee convenes every December, in the calendar year before the induction ceremony in July. The Early Baseball committee will convene decennially in years ending in 0, and the Golden Days committee will convene every five years, in years ending in 0 and 5. The Today's Game and Modern Baseball committees alternate their meetings in that order, skipping years in which the Golden Days and Early Baseball committees meet. If a player fails to be elected by the BBWAA within 15 years of his retirement from active play (i.e., during his ten years of eligibility), he could still be selected by the BBWAA Veterans Committee.

It is interesting to note that there have been just as many ball players elected to baseball’s Hall of Fame from the Veterans Committee than have been elected from the official ballot voted on annually by the BBWAA members.