Remembering Dick Fowler on his 100th birthday

Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame inductee Dick Fowler (Toronto, Ont.) would’ve turned 100 today. Photo: Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame

March 30, 2021

By Kevin Glew

Canadian Baseball Network

No one could’ve predicted that Dick Fowler would make history on September 9, 1945.

Just eight days earlier, the 6-foot-4 Toronto native had returned to the Philadelphia A’s pitching staff after a 30-month term in the Canadian army.

Though Fowler had pitched in a recreational league while in the service, he was understandably underwhelming in his first three appearances back with the A’s, allowing 11 runs in 11-2/3 innings.

“I can honestly say I was never in worse shape in my life,” Fowler told a reporter in 1947 about his conditioning after returning from the army.

But Connie Mack’s bottom-dwelling A’s, with another lost season winding down, required a starting pitcher for the second game of a doubleheader against the St. Louis Browns that day and Fowler, who was a fierce competitor and anxious to re-establish himself as a starter, gladly accepted the assignment.

Led by shortstop Vern Stephens and first baseman Lou Finney, the Browns were a formidable opponent. They had won the American League pennant the previous season and had 25 more wins than the A’s heading into this contest.

Given Fowler’s poor conditioning and the fact that he had been asked to throw seven innings in relief just four days earlier, there were questions about his stamina. Would he able to pitch deep into the game?

The answer was a definitive yes.

Armed with an arsenal that included an mid-to-high 80s fastball, a nasty curve and a work-in-progress change-up, Fowler took the mound in front of 16,755 fans on a dreary, overcast day at Shibe Park in Philadelphia and dominated.

Throwing to Buddy Rosar, one of the top defensive catchers of the era, the crafty Canadian walked Browns second baseman Don Gutteridge in the third inning to nullify his chance for a perfect game. And he nearly lost his no-hitter to the next batter when mound rival Ox Miller, who was making his first major league start, clubbed a grounder up the middle that A’s shortstop Al Brancato had to range far to his left to corral and flip to second baseman Irv Hall for a force out of Gutteridge.

With A’s fans cheering his every out from the fifth inning on, Fowler poured every ounce of energy he had into each pitch. Rosar would later tell reporters that Fowler’s fastball seemed “unusually alive” that day.

The Canuck right-hander laboured in the latter innings, issuing single walks in the seventh and eighth frames, but there was never a question of him coming out of the game and he had just enough grit and guile to make it to the ninth with his no-hitter intact.

After retiring Miller on a fly ball to left to open the ninth inning, he walked centre fielder Milt Byrnes and up stepped Finney, the leading hitter on the Browns. The left-handed hitting first baseman watched a strike and then took a ball before hacking at Fowler’s third pitch and ripping a line drive over the head of A’s first baseman Dick Siebert. A hush went over the crowd and Fowler’s heart seemed to stop as he watched the ball twisting, twisting, twisting and then smack the earth about four feet foul.

After catching his breath, Fowler took a moment to collect himself, then reared back and threw a fastball that Finney topped to Hall who flipped the ball to Brancato who fired it to Siebert to complete an inning-ending double play. In nine innings, Fowler had held the Browns without a hit.

“I threw every pitch that Buddy Rosar called,” Fowler told reporters after the game. “I had been away for three years and I figured he knew the hitters better than I did.”

But even after tossing nine, hitless innings, Fowler wasn’t guaranteed a victory. Miller was almost equally as effective for the Browns, holding the A’s off the scoreboard and to just three hits – including a double by Fowler in the third inning – through eight innings.

Fowler later confided to Toronto Star reporter Trent Frayne that he was out of gas after the ninth and he couldn’t have pitched another inning.

Fortunately for him, in the bottom of the ninth, A’s right fielder Hal Peck, who once shot off two of his toes in a hunting accident, socked a ball off a loudspeaker on the right-centre field wall and chugged into third base with a triple. Hall then followed with a line-drive single over the second baseman’s head to score Peck and secure a 1-0 win. After Peck touched home plate, the A’s rushed towards Fowler just outside their dugout.

But in an extraordinary display of sportsmanship, Fowler escaped the grasp of his teammates and ran to the dejected Miller to shake his hand. The Canadian righty wanted to recognize that Miller had pitched his heart out that day too.

A testament to how much Fowler’s teammates liked him came when, after giving him a moment with Miller, they ran over and embraced him one-by-one before A’s fans picked him up and hoisted him on their shoulders and paraded him around the infield.

Even Fowler’s normally stoic manager was moved. Sporting his trademark business suit, the 82-year-old Mack left his customary spot on the A’s bench and walked out and put his arm around Fowler, no doubt feeling a sense of fatherly pride in the young pitcher his scouts had plucked from north of the border.

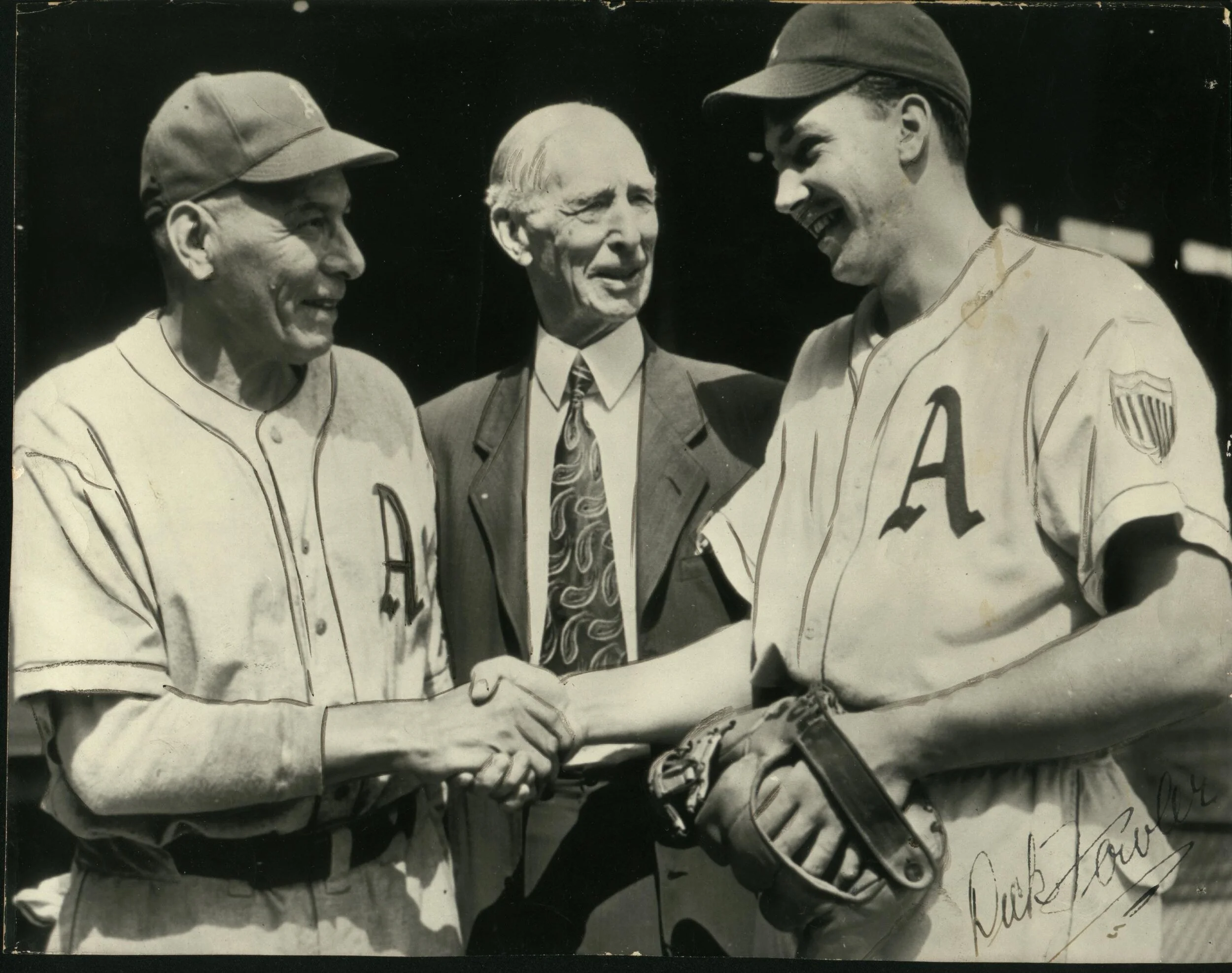

Dick Fowler (right) shaking hands with A’s legend Chief Bender after his no-hitter, while Connie Mack looks on. Photo: Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame

“Dick had a dazed look on his face and a big goofy grin,” recalled Phil Marchildon, a fellow Canadian who was also a key member of the A’s rotation, in his 1993 biography, Ace, of the on-field celebration after the no-hitter.

At one point, Fowler managed to sneak away from his teammates, who continued to celebrate in the clubhouse, to a phone booth under the stands and call his wife, Joyce, and his two-year-old son, Tommy, to share the news.

Philadelphia Inquirer reporter Hank Littlehales conducted the most extensive post-game interview with Fowler, in the right-hander’s hotel room.

“I felt fine from the very first inning,” Fowler told Littlehales. “I knew I had a good start toward a no-hitter, but strangely enough, I wasn’t worrying about it. It was a wonderful feeling when we got that one run . . . I’m a pretty lucky guy, I guess.”

In his article the next day, Littlehales praised Fowler for his “innate modesty” which was “perfectly blended with cool confidence.”

“He [Fowler] had a right to be elated – and he was,” wrote Littlehales. “He had a right, too, to be proud – but the manner of pride displayed was not of the smug, self-satisfied hue. Rather, it was the unprepossessing attitude of being grateful for the fielding and hitting support of eight Athletics teammates who helped make possible this red letter day.”

Of the 27 outs Fowler recorded, 11 were via the ground ball, eight were fly outs and he fanned six batters. Just five fly balls got out of the infield.

After the interview with the Littlehales, Fowler joined a group of teammates – including Marchildon – for some celebratory rounds at a local tavern.

Fowler’s no-hitter was the first thrown by a Canadian in the big leagues. It was also the first by an American League pitcher since Bob Feller held the Chicago White Sox hitless on April 16, 1940 and the first by an A’s pitcher since Joe Bush on August 26, 1916.

Author David M. Jordan, who wrote the 1999 book, The Athletics of Philadelphia, was a 10-year-old A’s fan in Philadelphia when Fowler tossed the no-hitter.

“I do remember that for the A’s fans around, it was exciting to have our just-returned Canadian airman throw a no-hitter, and it generated some hope for the future of the team in 1946,” recalled Jordan in an email. “We didn’t get too many of those excitements in Philadelphia in those days, so Dick Fowler did generate a good bit of talk, among the fans, in the papers, and on the radio.”

That performance was the highlight of Fowler’s 10-year big league career that saw him evolve into one of the A’s most reliable starters in the late ’40s. Fowler would toss at least 14 complete games in each season from 1946 to 1949. His resume also boasts two, 15-win campaigns (1948, 1949) and he finished in the top 10 in the American League in shutouts three times (1947, 1948, 1949).

After hanging up his playing spikes, Fowler settled in Oneonta, N.Y. – his wife’s hometown – where he worked in a department store and later as the night clerk at the Oneonta Community Hotel. He also coached one of the town’s first Little League teams.

Sadly, Fowler was diagnosed with both kidney and liver disease in 1972 and he passed away on May 12 of that same year when he was just 51 years old.

He was inducted into the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame posthumously in 1985.