Three diamond medals for Sobchuk then on to Regina Pats, Cincy Stingers

Sobchuk excelled in ball but hockey was his true calling

By Danny Gallagher

Canadian Baseball Network

Dennis Sobchuk had just won a bronze medal in baseball for Saskatchewan at the Canada Summer Games in New Westminster, BC, in 1973 and was barely back home in Lang when he got a phone call that would shape his career and change his life.

The caller was Bill DeWitt Jr., a wealthy, 31-year-old St. Louis native, who had spent most of his life in Cincinnati. DeWitt was a Yale University economics major and a Harvard University masters grad and Cincinnati Reds minority shareholder, who knew Sobchuk as a hockey player, not as a ball player. DeWitt was aware Sobchuk had scored a headline-grabbing 67 goals and added 80 assists while playing junior hockey for the Regina Pats in 1972-73. Some hockey scouts and executives thought Sobchuk was the second coming of Jean Béliveau, who was the protege’s favourite player.

“We have a franchise in the WHA ... the Cincinnati Hockey Club,’’ DeWitt told Sobchuk. “Would you be interested in signing with us? We don’t have a team yet.’’

The wide-eyed, Sobchuk was listening. A city with no team, no arena and no nickname in a bold new league trying to face off against the NHL for talent. So DeWitt, the quasi-general manager and Sobchuk hung up. There were more phone calls and then it was arranged that Sobchuk would fly to meet with DeWitt.

Trying to digest all of this stuff and trying to savour his bronze medal at the same time was wonderful for Sobchuk, one of the most sought-after juniors in Canada’s history when he with the Pats.

“I was a pitcher with a great bat and I could run like a deer,’’ Sobchuk said. “I was also a shortstop, a centre fielder. I had a great fastball but I couldn’t hit the plate. I threw hard and when I got pissed off, I threw harder.’’

Sobchuk had grown up admiring Hall of Famers Don Drysdale, Sandy Koufax, Bob Gibson and Juan Marichal and as far as the Expos go, his hero was outfielder “Le Grand Orange” (Rusty Staub). In his teens he played against future Houston Astro great Terry Puhl (Melville, Sask.).

“Sometimes, I think baseball was to be my sport,’’ Sobchuk said. “I was on three championship teams: the gold medal team at the Saskatchewan Summer Games in Moose Jaw playing for Weyburn; the bronze medal we won in BC while I played for Regina; and the medal we won in Souris, Man. when we played for Weyburn at the Western Canada bison championship.’’

Sobchuk was a guest speaker with immortal Ted Williams at a Saskatchewan banquet in 1974. What many people may not know is that Sobchuk’s son Justin pitched in the minors for the Oakland A’s, who drafted him in 1999.

“Yes, baseball was a big part of my upbringing in growing up in Saskatchewan,’’ Sobchuk said.

But hockey would mean more for him in the long run. So Sobchuk, his father Harry and his mother Anne flew to meet with DeWitt. Eventually, Sobchuk wasn’t involved in the negotiations for a contract. His parents went face to face with DeWitt and agent Art Kaminsky.

“I was the point man,’’ DeWitt told me of his involvement with the Cincinnati team. “We applied to the NHL but they turned us down. That’s when the leagues were fighting for players. Underaged players could be signed by the WHA. Our scouts said Dennis was the top prospect in Canada and that he would be tops in the NHL draft. I got to know Dennis and his parents. They brought along Dennis’ brother Gene. They wanted him on the team, too.’’

As Sobchuk said of the phone chat, DeWitt sales pitch included, “We have a franchise, we don’t have a rink or a team. Would you be interested in signing with us? We will sign your brother Gene and we will sign your father as a scout.’ Bill’s family had lots of money. Every Canadian boy wants to play in the NHL. I was touted as the No. 1 pick in the NHL -- they couldn’t verify it because I was a year away from the draft. The Los Angeles Sharks of the WHA wanted to sign me for a year. Terry Slater of the Sharks wanted to fly me out. I turned them down. I still have the letter.

“I was thinking, ‘I’m making $240 a month with the Pats and I could be making $7,000 a month in the WHA.’ The Washington Capitals were calling me every day to come and play for them in the NHL. ‘Break the contract,’ the Capitals told me. But I said no.’’

So what did Sobchuk do? He returned to the junior ranks and played another season with the Pats. Again, he his totals were off the charts: 68 goals and 78 assists. He sparked the Pats to the Memorial Cup championship, which to this day, is the last one the franchise has enjoyed. Go figure.

In the meantime, Sobchuk decided to sign with the Cincinnati club, which would be called the Stingers. Bobby Hull had inked a contract worth $1-million per season with the WHA’s Winnipeg Jets and DeWitt agreed on a deal with Sobchuk, unheard of money in those days.

“Ha,’’ DeWitt said when I asked him about the amount and the years involved. It also was a $1-million deal, although it was stretched out. “It was a 10-year deal worth $100,000 a year,’’ DeWitt said. Not Bobby Hull money but still it was earth shattering for an underage junior.

“It really was,’’ DeWitt said of the dollar amounts for that era. “The two leagues were signing free-agent players yet to be drafted to elevated contracts.’’

Until the Stingers could get Riverfront Coliseum next to Riverfront Stadium up and running, it was arranged that Sobchuk would play the 1974-75 season with the Phoenix Roadrunners in the WHA. Odd but true. His first pro season saw him score 32 goals and add 45 assists in the desert. He had lived up to his billing. Then he found his way to Cincinnati for the 1975-76 season.

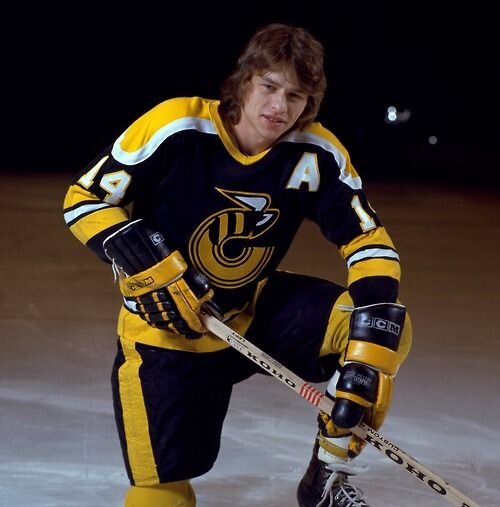

When Sobchuk landed, he wore No. 14, the same number worn by Reds baseball great Pete Rose and the same digit worn by Bengals football icon Kenny Anderson.

“It was the wrong city to be wearing No. 14,’’ Sobchuk said. “Pete Rose was a super-super-superstar. No. 14 is a very highly thought of number, a proud number. Kenny was the No. 1 player for the Bengals but I wasn’t in their category. I was proud to have 14. I had worn 14 in Regina. The Pats retired my number. Cincinnati is called the Queen City and Regina is called the Queen City.”

Sobchuk lived up to his own billing, up to DeWitt’s expectations and up to the standards of some seven Stingers shareholders, including Brian Heekin, a lawyer with old-family money in Cincinnati, and Bob Castellini, who owned a trucking business and a fruits and vegetable conglomerate on the riverfront. Everyone, it seems, shipped goods on either the Licking and Ohio rivers which border Kentucky.

“Dennis was a great guy,’’ said Castellini. “I remember when he first came into town. When I met him, I was very impressed. I always liked the guy. He came up through the junior ranks and was one of the best we ever had.’’

Again, like he had with the Pats and the Roadrunners, Sobchuk was stellar in his first Stingers’ season: 32 goals and 40 assists. The 1976-77 season was even more sensational: 44 goals and 52 assists. Among his teammates were Blaine Stoughton, Mike Liut, Mike Gartner and Mike Pelyk.

One of his coaches was Jacques Demers, who was coach of the Stanley Cup champion Montreal Canadiens in 1993.

“Dennis was a centre, a dominant figure on the ice, very fast and had a good shot,’’ DeWitt said. “He really was the face of the franchise the first couple of years. He had a nice career. He was the one we were hoping to build the team around.’’

Somewhere in there, Sobchuk met legendary Bengals owner Paul Brown, who gave him a Bengals ball cap with CB on the front. Sobchuk still has that hat. The prodigy was also placed three feet from Gerald Ford at a downtown Cincinnati reception at a time when Ford was running against Jimmy Carter in the U.S. presidential election.

“I was with probably the most important man on earth in President Ford,’’ Sobchuk recalled. “I couldn’t believe it. It was an out-of-body experience. There were 40,000-50,000 people at Fountain Square. People were hanging out of windows.

“They asked three Reds, three Bengals and three Stingers to be present. Hugh O’Brian (Wyatt Earp) and Peter Graves were there. I couldn’t vote but I had a name. Think about it, where I came from. I’m a Canadian from Lang, a town of 1,450 people. I’m a country bumpkin who excelled in hockey. I was very vulnerable. I was like a watermelon coming down a garden hose.’’

Indeed, Sobchuk had lived up to the end of the bargain. But by his third season, 1977-78, he was injured and less productive. That winter, he also was traded to the Edmonton Oilers and that was almost the end of the Stingers.

Again, DeWitt and his partners applied to enter the NHL as one of the four new cities the veteran league had wanted to absorb and merge from the WHA. The NHL said no to Cincinnati again but paid DeWitt and his partners a go-away severance of $1.5-million. The NHL said yes to the Jets, Oilers, Quebec Nordiques and New England Whalers as its new partners.

DeWitt confirmed that he and his partners had discussions with the NHL about merging the Stingers into the NHL but “when we really got down to it, the NHL powers that be’’ said no.

The Cincinnati experiment did not succeed because of attendance problems. Riverfront Coliseum had a capacity of 16,000 but the Stingers drew crowds of not much more than 7,000 most nights. Sobchuk didn’t have the star wattage of Rose or Anderson but he enjoyed his time under the lights.

“I met Pete Rose numerous times. He was from Cincinnati. Charlie Hustle,’’ Sobchuk said. “He worked his butt off to be the best player he was. 4,256 hits. It’s sad, he should be in the hall of Fame. He was Mr. Dedication.

“I was an opposite polar. I was given a gift not to practice. I hated practice. Pete worked at being No. 1. I drank. He was the opposite. He didn’t drink. He was Mr. Cincinnati. I admired his dedication to baseball, his work ethic. I had no work ethic. I loved my cocktails. I had my fun.’’

Yes, off the ice, Sobchuk was having nothing less than fun. His time away from the rink was a fog, a blur, many bleary-eyed nights of drinking, womanizing and socializing until all hours of the night. Like Rose and Anderson, he was the toast of the town. He once played in the rock band Chicago at the Playboy Club.

One night after midnight like he did many nights, Sobchuk went into the cheesy-sounding but ultra-popular haunt called Sleep Out Louie’s on Riverfront near an old fire hall.

“It was a bar that everyone went to,’’ Sobchuk said. “It was near the arena, the football stadium and the ball park. It was a place to go and enjoy my beers, especially Happy Hour. It was my way of getting away from the real world. Our lives are fast, airports, bars. I was the face of the Stingers. We lived in a small fishbowl, round and round, that’s the way my world went. With my long hair, I took in the rock concerts. It was fast and vibrant in Cincinnati.

“When the game was over, you still had a lot of adrenalin so you went to the bar. It was a place to unwind when the game was over. We made a lot of money and spent a lot of it on booze and women. We were renegades and rebels with long hair. I spent half my money on women and booze and I wasted the other half. I was living outside the world. I felt like I was in the third person.’’

Sobchuk fell easy for a bartender serving him drinks. They would talk and talk.

“She was a pretty lady. I actually hit on her first,’’ Sobchuk said. After getting to know each other, Sobchuk dug up the courage to ask the gal this question, “Any chance I can take you out on a date some time?’’ The girl’s reply, “I’m seeing someone but if you want, I can suggest my girlfriend, my roommate, for a blind date. She works for Delta Airlines in reservations. She works from four in the afternoon until midnight.’ That worked good for me because our games would end late at night.’’

The barmaid, Carol Woliung, was seeing a guy she would eventually marry: Pete Rose. Woliung, a former Playboy bunny and Philadelphia Eagles cheerleader, who would be Rose’s second wife after they continued their relationship when Rose switched from the Reds to the Philadelphia Phillies in 1980.

The woman Carol introduced to Sobchuk was Julia Huffmann. He was 6-foot-2, she was 5-foot-1. The height discrepancy didn’t bother Sobchuk..

“We met Nov. 23, 1977,’’ Sobhuck said. “I met Julia at Sleep Out Louie’s but she was not impressed. She didn’t think too highly of me. She thought I was too flamboyant, too big-headed, maybe too cocky. I had broken a bone in my wrist and I had a cast on when I went to meet her on the blind date.’’

Sobchuk convinced Huffmann to go out on a second date. This time, they passed on the noisy, dim-lit Sleep Out Louie’s for a place that was quieter and where they didn’t have to talk hockey. At the time, Sobchuk was on the injured list and didn’t make a Stingers’ road trip so they arranged to meet.

“The music is too loud at Sleep Out Louie’s,’’ Sobchuk told Huffmann. “We went to another place so we could talk in a normal mode. We kind of hit it off. We got to date more. She didn’t know hockey. She never went to any games. It’s funny I got traded to Edmonton so there was a long distance thing.’’

Sobchuk and Huffman soon got married and their union is rock solid. Earlier this year, they celebrated their 40th wedding anniversary. They lived for a period in the 1980s in Regina where he became an assistant coach with the Pats and then head coach of the team.

He made the decision to go back to Regina, although he got a 1988 call from old friend DeWitt, asking him if he wanted to take a job with Coca-Cola in Cincinnati which was celebrating its bicentennial that year. At that point, the entrepreneurial DeWitt and a partner Mercer Reynolds owned the Coca-Cola Company of Cincinnati, an enterprise they sold long ago.

Julia had finally picked up her bachelor’s degree in broadcasting from the University of Cincinnati so she took a job as the weather girl at a Regina TV station.

“My wife was more popular than I was. I’d be introduced as the husband of Julia Sobchuk because weather people are the most important people in a city,’’ he said, chuckling.

Later, the Sobchuks moved to Calgary for three years. Then CCM came into the picture again. He accepted a job as CCM’s pro rep west of the Mississippi River and he settled in Bellingham, Wash. The Sobchuks later made their home for 15 years in Phoenix, where Sobchuk always wanted to live even though he laughs that it took 35 years to get back there after he played for the Roadrunners in 1974-75.

They enjoy the 105-degree heat as opposed to the 52-below weather in Canada. In Phoenix, Sobchuk is a property superintendent, who builds and flips houses and helps manage a golf club called Mirabel. A few weeks ago, though, the Sobchuks decided to move back to Bellingham where a daughter lives but it will be 2020 before the move is official.

Sobchuk chuckles when he tells the story about his time in Edmonton when he was healthy enough to make a road trip back to Cincinnati. He got approval from Oilers GM Glen Sather to take his new wife back to Cincinnati so she could see her parents. By then, a new player had showed up to play for the Stingers. His name was Mark Messier. Sobchuk and Messier got into a fight and it didn’t turn out good for Sobchuk.

“Messier puts me down. He wins the fight,’’ Sobchuk said. “The story goes that Sather drafted Messier for the NHL because he beat the crap out of Sobchuk.’’

Messier merely went on to become one of the greatest players in NHL history. Sobchuk could have been like Messier but his playing career was cut short. He did get to play with a kid by the name of Wayne Gretzky with the 1978-79 Oilers but when the WHA and NHL merged, his career took another path. The Oilers were able to protect two players from their WHA team prior to the NHL draft and Sobchuk wasn’t one of them. Sobby was bypassed in favour of this guy Gretzky and another.

Sobchuk would never be the same. He played for the Detroit Red Wings and Quebec Nordiques. His time in Regina was legendary in the early-to-mid 1970s. Brother Gene had been signed by the Pats and Pats general manager Del Wilson saw Dennis hanging around at the official signing. Wilson asked Dennis, then 16, “do you play hockey? Why don’t you come to camp?’’

His signing bonus was a pair of CCM skates and they gave him No. 12 to wear. Later, he switched to 14. One of his Pats teammates was burly Clark Gillies (Moose Jaw, Sask.) who was a diamond prospect in his youth and was signed as a free agent by the Houston Astros.

“Clark was a big catcher. He had an unbelievable arm like Jethro Bodine. He didn’t have to stand up to throw the ball to second if someone was trying to steal,’’ Sobchuk joked.

As he looks back to his days with the Stingers, Sobchuk delves into fondness, realizing that the Stingers played in a difficult sports market.

“I was there for two years and I was in the top 10 in scoring,’’ Sobchuk said. “It was a tough battle, a hard market with the Reds and Bengals. The Reds were winning. Everything was the Reds. They were in the midst of winning two straight World Series titles. We didn’t crack the bubble. We’d get the fifth page in the sports section. But Cincinnati is still close to my heart.’’

While growing up and playing ball in Saskatchewan, Sobchuk was the talk of major junior hockey in all of Canada while playing for the Pats. His WHL rights as a junior were owned by the Estevan Bruins, who were transferred to New Westminster, BC, the same town where he won a baseball bronze. But the Pats did the unthinkable and traded five players to New West in order to get him to Regina.

Some 46 years later, Sobchuk and Guy Lafleur were invited to the 100th anniversary of the Pats and the 100th anniversary of the Memorial Cup in Regina in 2018 as the top two junior players of all time in Canada, Sobchuk from Western Canada, Lafleur from the East. This was at a time when the Pats were and still are the oldest junior franchise in Canada.

“It was an unbelievable honour,’’ Sobchuk said. “The 2018 season was 44 years after we had won the Memorial Cup. NHL players have a whole career to try to win a Stanley Cup but junior players only have a few years to win a Memorial Cup. There were better players than me in Lang but they didn’t have the fortitude. I blossomed in Regina.’’

A few weeks ago, Sobchuk’s mother died in Weyburn, Sask. at age 89. She had bravely fought the ravages of multiple sclerosis for close to 60 years. She had been in a wheelchair and bed-ridden since 1979.

“My mother gave us a lot of determination,’’ her son said.

And what became of DeWitt and Castellini? They remain close and run Major League Baseball franchises. How about that? DeWitt, 78, purchased the Cardinals in his hometown of St. Louis in 1995 after stints as a minority investor with the Orioles, Reds and Rangers. Officially, he’s the Cardinals chairman and CEO. The Cardinals have won two World Series under DeWitt’s watch. His father, also named Bill DeWitt, owned the Reds and St. Louis Browns for years.

DeWitt Jr. was a bat boy for the Browns as a nine-year-old and his uniform was used by 3-foot-7 Eddie Gaedel when he made that famous pinch-hit appearance Aug. 19, 1951.

Reds 1B Joey Votto (Etobicoke, Ont.) talks with Reds owner Bob Castellini on a recent opening day

Castellini, 78, purchased controlling interest in the Reds in late 2005 and became CEO. He had been a minority shareholder in the Cardinals under DeWitt for close to 10 years. His share in the Cardinals was sold as a condition of the acquisition of the Reds.

Because the Reds train in Arizona, Sobchuk gets to see Castellini once in a while while DeWitt’s Cardinals train on the other side of the state in Jupiter.

“Two fine men,’’ Sobchuk said of DeWitt and Castellini.

Talking of fine men, so is Sobchuk.