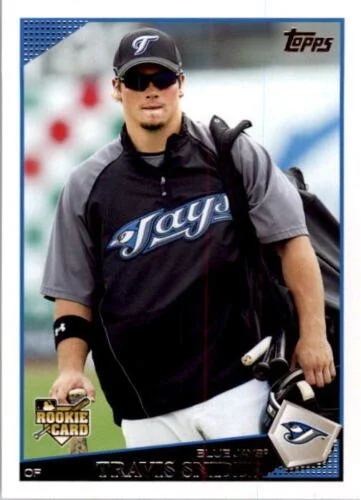

Verge: Ex-Jay Snider sharing experiences to be mental health advocate in youth sports

Travis Snider is hoping to

May 12, 2024

By Melissa Verge

Canadian Baseball Network

Alone in a hotel room, with no screaming crowd and bright lights to distract him from his own mind, Travis Snider spirals.

The Toronto Blue Jays outfielder is struggling at the plate, with his self worth, and with unhealed childhood trauma that he’s tried to repress.

“I still never got to the point of grieving, of processing these emotions to where I could just let go of it and go play the game,” Snider said. “I was always carrying that baggage with me.”

The talent is there for the Blue Jays’ first-round draft pick, but his mind is just as much an important part of his success in the game as his body.

And his mind is wracked with anxiety and self-doubt, and ultimately plays a part in him ending his career in 2021.

But instead of disappearing after retirement, Snider has become a prominent voice in the sports industry, a raw and vulnerable advocate for mental health in youth sports by sharing his own experiences.

In his life that has been full of adversity, overcoming that is what has led to success and opportunities post baseball. He created the company 3A athletics with his partner, Seth Taylor, where they’re helping strive for a healthier culture in youth sports.

Through his own challenges, he’s hoping athletes working their way up in the game can have a healthier future.

In his career, the weight of expectations and of childhood trauma that had yet to be unpacked followed Snider from city to city. It was invisible, but it was heavy, crushing a young and talented ball player who was fighting much more than a battle between him and the pitcher that showed up on Sportsnet every night.

“I would go into these month or two-month slumps at the plate, but really what I was dealing with was a mental and emotional rollercoaster that I tried my best to suppress,” he said.

He had his eyes set on being a middle of the order guy, a Hall of Famer. His view of himself was so closely tied to his job as a professional baseball player, that when it went south, it was a dark and downward spiral.

There was a lot going on behind the scenes for him, not just related to his struggles at the plate, but different layers of suppressed trauma that he tried to deal with on his own.

There was a fear of abandonment that he hadn’t worked through, growing up with two parents who struggled with addiction issues throughout his teenage years and early adulthood. When he was called into the Blue Jays office and sent down to triple-A in April of 2009, it triggered those feelings from his past he had pushed down into his subconscious.

“The abandonment thing and feeling alone is a big trigger for me,” he said. “And when you're with a group of guys and you're on the team and the next thing you know you're getting called in the office and you're going back to Las Vegas [it’s triggering.]”

It’s those experiences that have made him passionate about starting at the grassroots level, and helping young athletes, parents, and coaches better understand how to deal with the complex emotions that players are going through.

Along with 3A athletics, he’s worked alongside Seth Taylor on a guidebook called Hero, that has workbook pages with prompts for players and parents. It’s a very personal project for Snider, who wants to encourage open conversations, bigger than baseball. Like, is this what their child really wants to be doing, and are they happy, he said.

“Parents are putting this pressure on kids in sports for a lot of the right reasons, but not understanding how fragile kids are in terms of understanding what makes them feel loved and what makes them feel valuable,” he said.

The pressures were intense for him beginning in youth baseball. He was put up on a pedestal early on, tying his value to how he performed on the baseball diamond.

And when he had a rough outing? It led to feelings of inadequacy. Flashback to 25 years ago, at a tournament Snider was pitching in. He walked a few batters.

Later, tears ran down his face. He was hyperventilating. The then 11-year-old was having a panic attack.

It wasn’t the first one the athlete would experience.

Although they didn’t follow him to the Major League level, once there, he experienced immense levels of anxiety.

Now that the 36-year-old’s baseball career is over, he’s hopeful that he can help change the narrative for other young and talented athletes working their way up in the system and dealing with a multitude of different emotions. Not only that, but for professional athletes searching to find meaning in a life after baseball.

At a players alumni association event last fall, he spoke on a mental transitions panel with former teammate J.P. Arencibia. He saw how other athletes who had hung up their gloves were struggling with an identity crisis.

“It didn't matter kind of how much money people had made, or what kind of success and failure they had in their career, we were all kind of walking around there lost because we’ve dedicated our whole lives to playing baseball and we've [always] been known as baseball players,” he said.

It’s important to start at the bottom, to raise kids who know they're more than just the sport they play, Snider said.

Their value isn’t determined by how or if they perform on the baseball field.

“The more we can get done at this level, the next generations of players that are going to be coming up are going to be dealing with far less of this crisis.”

“Who they are and what makes them valuable, and how they are much bigger than what somebody says about them on Twitter because they went 4-for-40 and they're getting sent down to Triple A,” Snider said.