108: R.A. Dickey - not the knuckleball - responsible for slow starts

As always, Dickey got off to a slow start in April, but has since turned things around in May. Photo: Nathan Denette, Canadian Press.

May 15, 2016

Canadian Baseball Network

R.A. Dickey is now in his fourth season with the Toronto Blue Jays, and every April fans have had to listen to the same drawn-out excuses as to why the knuckleballer - and former Cy Young award winner - starts so damn slow.

Over his career, Dickey has posted a 5.12 ERA in the month of April, which is significantly worse than his career ERA of 3.98, and much, much worse than his 3.41 ERA in the month of September.

And so far it’s been the same old story for Dickey in 2016.

In five starts this past April, he had his worst ever beginning to a season, recording an absolutely awful ERA of 6.75.

However, when the calendar turned to May he once again morphed - somewhat inexplicably - into a completely different pitcher.

Through his first three May starts he has a Jake Arrieta-like ERA of 1.27. He’s pitched 21.1 innings over that three game span while only giving up five runs.

His most recent start against the Texas Rangers on Friday was also a true gem - and one that Dickey really needed seeing as he was the only Jays starter not pulling his weight. He hurled eight scoreless innings while only allowing three hits in that start, which was undoubtedly one of his best in recent memory.

Although pleased with his performance after the game, Dickey did voice some of the same frustrations held by Jays fans in regards to his consistent early struggles.

“I hate that I’m a slow starter, I really do,” Dickey told Sportsnet’s Barry Davis. “I’ve tried so many different things to start the year off better.”

At least that was a more honest, candid response than we’re accustomed to hearing from the sometimes overly-bookish Dickey.

I mean, who can forget that infamous “the knuckleball can be a very capricious animal” comment back in 2013? For the record, I still have no idea what on earth he was talking about ..

And it didn’t take long on Friday for Dickey to revert back to those more ‘Dickey-esque’ responses.

“When the sun went down, it got a little more humid, and that humidity is always big for a knuckleball,” Dickey told reporters in the clubhouse after defeating the Rangers. “I saw bigger swings in movement in the last three innings than I did in the first four or five.”

(Note that humidity, and the climate more broadly, has been long cited as an aggravating factor in terms of Dickey’s effectiveness - which I’ve always found odd considering his best years were in New York with the Mets).

To be fair, it hasn’t just been Dickey who has been disseminating this sort-of knuckleball lore - that somehow for it to be an effective pitch it has to be hot, humid, summer, outdoors, windy (but not too windy), a full moon, the year of the dragon, etc, etc.

In fact, when it comes to the knuckleball it seems like everybody suddenly feels qualified to play the role of sports pseudo-scientist - and yes, that includes me.

Well, apologies to all the armchair engineers and de facto PhD holders out there, but the notion that Dickey’s slow starts can be attributed to the pitch, and not the pitcher, is simply not true.

***

To be honest, I’ve been curious for some time as to whether Dickey being a slow-starter was a personal struggle, or whether it could be part of a larger trend that perhaps plagues the majority of knuckleball pitchers.

In order to examine just how “capricious” of an animal the knuckleball truly is, I decided to look at the career stats of some of the more recent and well-known major league pitchers who made their careers by throwing dancing knucklers.

For the sample to be reliable, they had to have pitched at least into the 1980’s (aka the modern era), appeared in over 100 career games, and the knuckleball had to be their predominant pitch - which left me with seven pitchers:

- Tim Wakefield - 547 games (1992 - 2011)

- Steve Sparks - 270 games (1995 - 2004)

- Dennis Springer - 130 games (1995 - 2002)

- Tom Candiotti - 451 games (1983 - 1999)

- Charlie Hough - 858 games (1970 - 1994)

- Joe Niekro - 702 games (1967 - 1988)

- Phil Niekro - 864 games (1964 - 1987)

Upon closer examination, a few things became immediately apparent while studying this list.

First, knuckleball pitchers are extremely rare. Since 1905 there have been just 30. Of those 30, four are in the hall of fame but only one has a Cy Young award - R.A. Dickey.

Second, a good knuckleballer can essentially pitch forever. Three of those seven pitchers had careers spanning more than two decades (Phil Niekro, Joe Niekro, and Charlie Hough).

Third - and most importantly - the knuckleball does not magically get better over time.

(Sorry, R.A.).

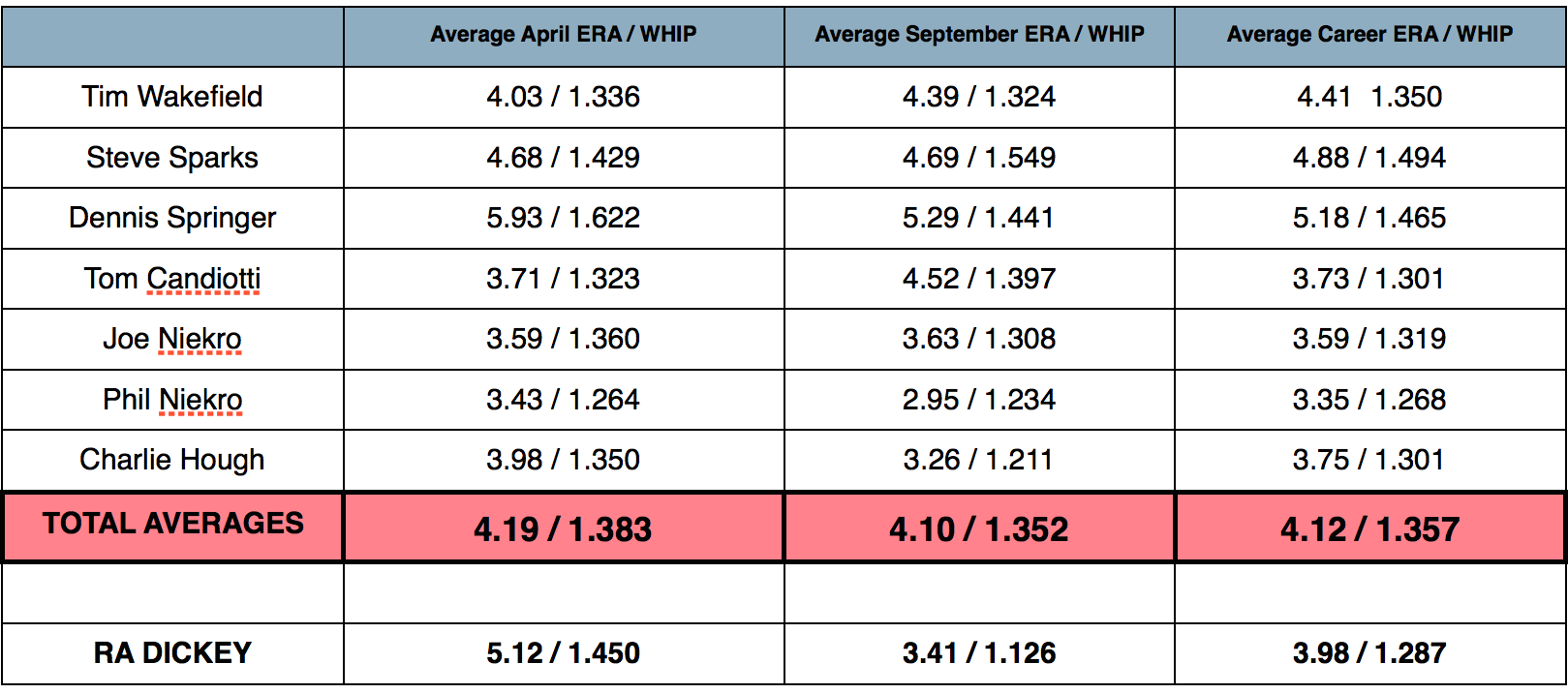

The average ERA in April for those those seven knuckleballers was 4.19, while their average WHIP was 1.383. Contrast that with their average career ERA of 4.12 and their average career WHIP of 1.357, and you’ll see that there is no real “slow-start” phenomenon - at least not one remotely close to the one experienced by Dickey.

Even when you compare all the averages in their first month of the season to that of their last month, Dickey’s numbers remain off the map. The average difference in ERA in April compared to September was just .09 - which is actually consistent with modern league averages.

Dickey, on the other hand, has a difference of 1.71 when comparing April and September. So ... ya ... your guess is as good as mine.

What this all seems to indicate is that the performance of a knuckleballer over the course of a season is really no different than anybody else who throws more traditional stuff.

If you look at the league-wide averages among pitchers over the past five seasons, the difference between April ERA and season-end ERA has been minuscule. It has only fluctuated by an average of .07 (up or down) - which is the exact same difference seen in the knuckleballers.

And in case it wasn’t clear earlier, please stop blaming the climate. Like I said, Dickey himself had his best years in New York ... and last I checked April can be pretty miserable there too. Also, Tim Wakefield pitched in Boston, and he actually got much worse as the season progressed.

Now this is in no way meant to vilify Dickey, or the pitch that earns him roughly $8-million per year. Because as much as the struggles are all on R.A., this also means the he gets to take credit for the success too.

And besides, the April woes over ...

So why am I even bringing this up?

***