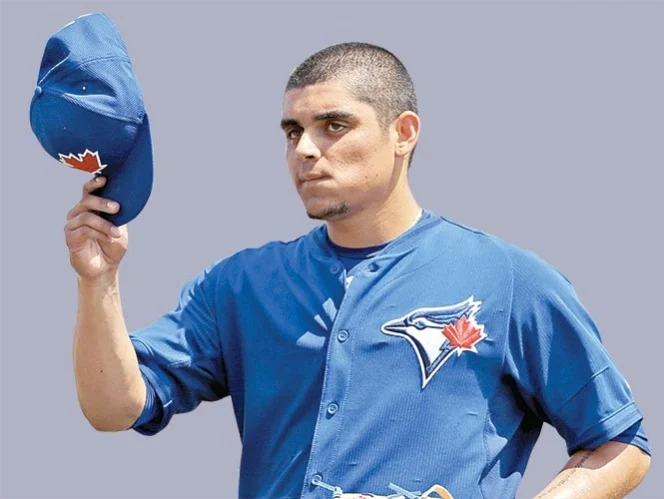

Osuna soaring but still far from his peak

By: Alexis Brudnicki

Canadian Baseball Network

TORONTO – Roberto Osuna has always had his back against the wall.

As his Toronto Blue Jays squad advanced from a do-or-die Game 5 matchup against the Texas Rangers to the American League Championship Series against the Kansas City Royals, the feeling was nothing new for him.

The 20-year-old right-hander has never wanted or dreamed of anything but baseball, and he has always felt as though continuing to play the game was and is his only option.

“I don’t know what else I could do,” Osuna said. “I didn’t go to school so I have no idea. I’ve just got to keep working hard and trying to be here for a long time because I don’t think I have any other options out of baseball. That’s been the same always.”

Osuna was born into a baseball family in a baseball town in Juan Jose Rios, Sinaloa, Mexico, and after tending fields with his dad for money, he left home when he was 12 years old for a better chance in Arizona. His only education is in America’s favourite pastime and his opportunity couldn’t come soon enough.

“I don’t remember too many things,” Osuna said of his birthplace. “I only go to Mexico for two or three weeks at a time. But my city is what I miss most. It’s a small town and everybody knows each other. The rest of the time growing up I lived in Arizona…That’s why I don’t have too many favourite things about Mexico. The food, obviously, and the baseball I miss. The city where I live is a baseball city.”

He was seven years old when he had his first inclination that he could reach the major leagues. The young flamethrower – who had earned the nickname Little Cannon – isn’t sure what sparked the moment, but it was then that he knew his destiny would land him on a big league field. The dream started to become real, years before the Mexican League stars and scouts and friends of the family told Osuna at 12 that he had something special.

“I always threw hard but I didn’t have the control because I was too young,” he said. “But I always threw hard and I always knew I wanted to play in the big leagues. I was 12 years old and all the best players were behind me saying, ‘You’ve got the potential to play in the big leagues,’ and all those things, but my first feeling was when I was seven years old.”

After permanently leaving Mexico before entering his adolescence, Osuna would return to play for the Diablos Rojos del Mexico in the Mexican League – a circuit where the average age is almost 30 – at the beginning of his summer as a 16-year-old, after getting his start the winter before at age 15. There he drew the attention he needed, signing quickly and joining the Blue Jays organization.

His experience landed him in the Appalachian League with the Bluefield Blue Jays, skipping the rookie-class Gulf Coast circuit where the vast majority of teenaged players start their professional journeys. Almost untouchable in seven Bluefield appearances, Osuna moved up to the short-season Northwest League, joining the Vancouver Canadians.

“In Vancouver he was absolutely dominant as a 17-year-old, mowing through teams,” one baseball executive said. “He pitched against [big leaguers] in spring training and he did a nice job. He looked comfortable and it’s probably because he was exposed to such high-level competition at a young age, getting experience in the Mexican League as a 15-year-old. He’s a very confident guy on the mound and there’s not too much that phases him.”

The next season he was promoted to the Midwest League and joined the Lansing Lugnuts. The then-18-year-old managed 42 1/3 innings before succumbing to a tear in his ulnar collateral ligament and undergoing Tommy John surgery.

His success and progress grinded to an immediate halt, and Osuna felt as though everyone who had jumped on his bandwagon along the way was abandoning it and him. He still had the support of his family and Toronto’s staff – with strong assistance from his father, Willie Collazo, Tony Caceras, Jeff Stevenson and Jose Ministral – but he had developed a list of doubters that he wanted so badly to prove wrong.

“The lowest point in my career was when I had my Tommy John,” he said. “Nobody trusted me, everyone thought I was done, so that was the lowest point in my career. But I wasn’t worried. I had been working so hard trying to get better than ever and that’s what I did. But everyone was saying, ‘Osuna you’re done, you’re done.’ It’s part of the business.”

His comeback happened quickly and Osuna was on the mound less than a year later, throwing several simulated starts at Florida Auto Exchange Stadium – home of the Dunedin Blue Jays – before officially getting one inning in the Gulf Coast League and finishing the season with Dunedin.

That was last year.

It is a fact that is now hard to comprehend, and the last team Osuna played for before joining the big-league Blue Jays out of spring training was the Mesa Solar Sox. He was the third-youngest player in the Arizona Fall League, then lacking command but impressing enough to be named a Fall Star in November.

Not even five months later, he was in Toronto as the youngest among an Opening Day roster that included rookies Miguel Castro, Daniel Norris, Aaron Sanchez, Devon Travis, and Dalton Pompey, Osuna’s Solar Sox teammate.

Now, still not quite fast forwarding a full 12 months from the Fall League, and just 15 months and days after throwing his first post-surgery pitch, Osuna is in playoffs with a full year in the bigs under his belt. He posted a 2.58 ERA over 69 2/3 innings and 68 regular season appearances. The righty took over as the team’s closer at the end of June and notched 20 saves.

In four postseason outings and 5 2/3 innings, he hasn’t allowed a baserunner. He came in for the last five outs of the American League Division Series and struck out four, absolutely shutting down the Rangers.

And he’s not done.

“The highest point, I don’t think I’ve been there yet,” Osuna said. “I’m here now but there are a lot more good things to come.”