Ex-Expos, Jays among non-vested retirees looking for more money

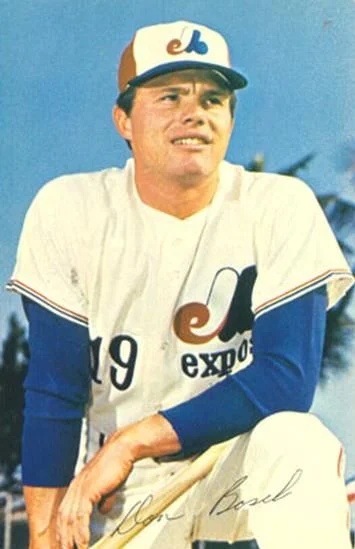

Former Montreal Expo Don Bosch is among the ex-major leaguers who feels he has been shortchanged by MLB and the MLBPA in retirement.

By Danny Gallagher

Canadian Baseball Network

Dennis DeBarr, an original Blue Jay, is barely getting by in Modesto, Calif.

Don Bosch, an original Expo, claims he isn't too bad off but really, he's just scraping by in Fort Jones, Calif.

DeBarr and Bosch are victims of a long-ago decision that left 500 remaining players like them with very little in the way of a pension even though they spent very little time in the majors. They are referred to as non-vested retirees.

Consider this: DeBarr's take-home pay in a lump-sum payment after taxes per year is $589 U.S. You read that right. It works out to close to $50 per month. DeBarr has a small pension based on a 25-year stint in construction and he will receive his Social Security money at age 65.

DeBarr appeared in 14 games for the 1977 expansion Jays but he accrued 74 days of service, which would qualify him under today's requirement standard, giving him a $34,000 annual pension.

"I don't call it a pension. I call it blood money, a bone that has been thrown at these men,'' said U.S. freelance writer Doug Gladstone, who wrote a book called A Bitter Cup of Coffee: How MLB and The Players Association Threw 874 Retirees a Curve. "The rules for receiving MLB pensions changed in 1980. Bosch and about 500 others do not get pensions because they didn’t accrue four years of service credit. That was what ballplayers who played between 1947-1979 needed to be eligible for the pension plan.

"Many of the impacted retirees are filing for bankruptcies at advanced ages, having their homes foreclosed on and are so poor and sick they cannot afford adequate health insurance coverage. They are being penalized for playing the game they loved at the wrong time.''

After income taxes and other fees, Bosch's annual take-home pay each February is $4,176.35, decidedly better than what DeBarr receives but it's barely sufficient to keep him going.

On top of that, Bosch gets the Social Security pension, which he would not reveal, after years of toiling in the construction and cast-stone business. That's what he lives on: a MLB payout and Social Security payments. His business "went under'' a decade ago so he has no savings so to speak of.

What ruffles Bosch's psyche is that his MLB payout cannot be transferred to loved ones or a designated beneficiary when he dies and further more, he doesn't qualify for any MLB health-insurance benefits under the Collective Bargaining Agreement negotiated between the players' association and MLB. What they receive is called "unqualified retirement payments.''

"I'm OK. I have enough to get by,'' Bosch, 75, was saying from his home near the Oregon border. "They signed a five-year contract a while back. I don't know if they can change it or re-negotiate it. To think we don't have medical insurance, that is devastating for older people.

"If you took every nickel I made from the time I started playing pro ball in 1960 to the time I quit, it would amount to what some of these guys these days make in one game. I feel like they treated us likes pieces of meat. We're disposable players,'' Bosch added.

Bosch didn't quite reach the four years of service required to be an official, vested retiree. He started his big-league career of 340 games with the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1966 and played two seasons with the Mets before being traded to the expansion Expos in time for the 1969 season.

Bosch is credited with scoring the very first run in the first-ever, big-league game played in Canada on April 14, 1969. He never played again in the majors following the 1969 season because of an injury.

There was no incident in particular that Bosch remembers but he said he hurt his left knee in 1969 when it locked up. He entered a Montreal hospital in July of that year and underwent surgery, if they called it that, in those days. He came out of the surgery a different athlete.

"It was exploratory surgery in those days. They gave me a butcher,'' Bosch said. "They took x-rays. I had knee surgery and never saw the doctor again. I was in the hospital and watched on TV when they (Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin) walked on the moon.

"I woke up in quite a bit of pain. I was in hospital for about a week. Nobody from the front office called me, not a player called me, not even a trainer to see how I was doing. There was no rehab. I was sent home to California. My knee was taped up so tight I couldn't bend my knee.''

One thing Bosch discovered the following year when he went to spring training and spent some time in the minors was that he just wasn't the same ballplayer because of the injury and surgery.

"Balls I could catch in my hip pocket, I couldn't get to them anymore,'' Bosch said. "I was not going to hang onto baseball until I was 40 years old. I was 27 years old. When you play at the major-league level and have knee surgery and you lose a step, that's the end of your career.

"That's what happened to me. I was marginal to start with. Then I had knee surgery and you're no longer good at what you do and that's to play centre field. I have six-inch scars on each side of the kneecap.''

For the last seven years, thanks to cooperation between the union and MLB, Bosch and other affected players have been receiving payments. Gladstone said the late union leader Michael Weiner was the person behind the thrust to giving these players some assistance. Weiner saw how important it was to care for these former players. Gladstone's book was released in 2010 so it helped spur action a year later.

MLB officials didn't have to negotiate a deal with the union to help out these players. The deal in the old days was that a player had to reach four years to qualify for a pension. If you didn't, then you got nothing. At least, these players are getting something. The maximum any one of these non-vested retirees can get each year has also been capped at $10,000.

Gladstone bemoans the fact that the union's players' pension and welfare fund is valued at close to $2.7-billion, according to Forbes magazine. Union publicist Greg Bouris said he doesn't know what the fund is worth but admits a lot of money is going to be needed to pay pensions for vested retirees over the coming years.

“To say the players’ association has abandoned these non-vested players is a gross miscalculation,’’ Bouris said. “MLB had no obligation to bargain over these benefits. To their credit, they agreed to negotiate this program. They felt it was something that had to be done. The greatest accomplishment is to be able to provide this money on an annual basis to the non-vested retirees.’’

Among the other Expos, who are non-vested retirees are Canadian Bill Atkinson of Chatham, Ont. Then there are guys like Gerald Pirtle, who appeared in 19 games, all of them in relief. All told, over the three months he was on an active major league roster, he notched 25 2/3 innings to his credit.

Nowadays, as Gladstone pointed out, that would guarantee Pirtle a minimum pension of $34,000 based on a player being on an active roster for at least 43 days.

Other former Expos on the non-vested list include Don DeMola, Pat Scanlon, Jim Cox, Jeff Terpko, Garry Jestadt and Bill Dillman. Other former Blue Jays besides DeBarr in the mix include Steve Grilli, Tom Bruno and Jeff Byrd.

Atkinson said he probably would have qualified for the four-year service period had it not been for an injury he suffered during the 1978 Pearson Cup exhibition game between the Expos and Blue Jays. In an ill fated decision, Atkinson was sent home on a suicide-squeeze play.

"I blew my groin out,'' Atkinson said. "My legs were the size of your waist.''

In the end, Atkinson was never the same, just like Bosch. He never played again in the majors after a stint with the Expos in 1979.

"They went back to 1980 with this payout. If they went back one year to 1979, I'd be in the vested plan. I'd be happy,'' Atkinson said. "It depends on who you are. It's all politics. I'm not going to argue with it. It's one of those things. The money these guys are making today, they've got it made.''

Atkinson, 63, took his Canada Pension Plan at age 60 and in two years, he will get his Old Age Security pension. He also is helped out by a pension based on his 25-year stint as a mechanic with Crown Cork and Seal.

One man close to all of this brought up the point that in most industries such as GM, Ford, newspaper companies and the like, there is no such thing as retroactive pay for employees with very little period of time worked. He brought up the point where somebody who had only worked a few months wouldn't be cared for by most or all companies with any back pay.

"This plan is for players who weren't in the majors very long,'' said a person close to the scene.

When DeMola finished playing, he spent a long time in the fur business and currently sells beds for Sleep Number. He has heard that there is close to $3-billion in the MLBPA pension fund, according to the alumni group MLBPAA. He said he grosses $6,500 and his take-home pay is about $4,800.

"I was told by a big guy with the MLBPAA that there isn't enough money in the pension fund to give us a regular pension. I find that laughable,'' DeMola said.

Bosch has self-published a 100-page book that you can obtain at amazon.com for $12 U.S. It's called A Second Journey Through Life. There is nothing in it about baseball but Bosch offers up thoughts that may be interesting to readers.

"It's intended as a coffee-table kind of book, something you can pick up anytime. Each page is different, a poem, some prose,'' Bosch explained.

It was Bosch's decision and his decision alone but he said has not communicated with anybody in baseball he played with since he retired. He doesn't consider himself a recluse but he just wanted to sever ties with baseball.

"I just wanted to move on with my life,'' Bosch said. "Nobody contacted me and I contacted nobody. I've never been bitter. I just moved on. I've got stories to tell and memories. I got to do what a lot of people didn't do. I got to travel and meet a lot of people. In 1969, we were a bunch of nobodies with the Expos. What could we do? We just weren't very competitive.

"I have one memorable thing that happened. I remember like it was yesterday. In May of 1969, the Cubs were supposed to play the Game of the Week but they got rained out so we were the backup game. It was sleeting ice rain at Jarry Park but we had to play anyway.

"Now here's the scene. We're playing Cincinnati in the top of the ninth. Cincinnati had runners at first and second with two out and we're ahead 3-2. Tony Perez is hitting and Elroy Face is pitching. I'm playing centre field and Perez hits one over my head and I caught it at the fence to make it three out. And we won. That’s my greatest memory with the Expos.’’

DeBarr was supposed to be the Jays' closer in their inaugural 1977 season but they lost so many games that he very rarely got into a save situation. in fact, he never saved a game.

"I do remember the fans were outstanding,'' DeBarr said. "I remember when we were in spring training and the pitching coach (Bob Miller) said that if you weren't good enough in baseball that you'd be doing what they are doing and he pointed to people working in construction in a field. I didn't like the pitching coach and I don't think he liked me. I was a Christian and maybe he thought that made me too soft a person. And I chewed licorice, not chewing tobacco.

"I remember before a regular-season game, Reggie Jackson and I met in left field and he said, 'Hey, rook, come over here.' We were both from the Oakland area. He was making a few million a year and I was making the minimum wage. He said, 'I put my pants on the same way as you.' There was one game I struck him out on a slider and we both looked at each other and he seemed to be saying,' Welcome to the big leagues.' ''

For many years, Bruno has operated Major League Adventures, a hunting and fishing-guide service based out of Pierre, South Dakota and he holds a "master captain" credential from the U.S. Coast Guard to operate a charter boat for hire. Bruno went to school in Port Aransas, Texas at the Sea Academy to take the necessary exams so he could be a boat captain.

The issue of non-vested payments hits a chord with Bruno. He thinks all players should be treated equal. If the current rule is that players can get a $34,000 annual pension based on only 43 days of service then the players of his time should get the same kind of money.

"I'm not going to be judgmental but the important thing is that we should get the same plan as they have now,'' Bruno said. "But nobody wants to acknowledge that we played Major League Baseball before 1980. It doesn't make sense. We'd like to be equal. We feel we're being penalized for playing Major League Baseball at the wrong time.

"I bet that if they changed the current rule to say that we all get the same kind of money like us that they'd be screaming all the way from Canada to Florida,'' Bruno said.

Just so you know, the non-vested players are officially paid with cheques that come from MLB but there is more to the scenario than that. According to Gladstone, this money actually comes from the Competitive Balance tax fund which is split between the union and MLB.

"That's what’s paying these guys,'' Gladstone explained. "It’s euphemistically called the Steinbrenner luxury tax because the Yankees always used to be over the payroll threshold. Any time a team goes over, they are taxed and that pool of monies, the CBT, is split among the league and union.''

In a letter that comes from the commissioner's office, these players are told, "These are gratituous payments paid from the general assets of the Commissioner of Baseball and do not create in you, or any other person, any claim against the assets of the Office of the Commissioner of Baseball. These payments are only payable to you while you are living. Neither your spouse nor any other beneficiary will be entitled to receive a payment.''