Glew: Remembering Roberto Clemente on the 52nd anniversary of his death

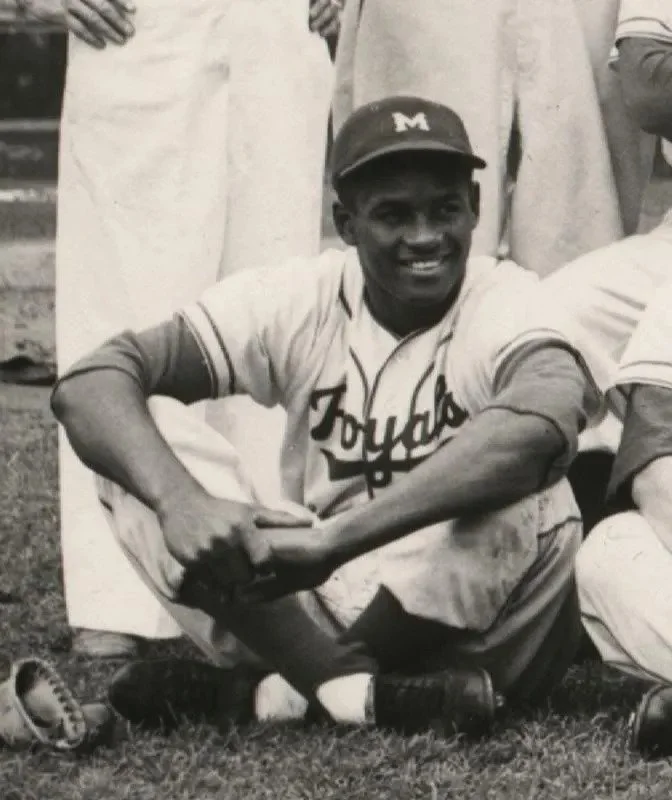

Roberto Clemente spent his first professional season with the Montreal Royals in 1954. Photo: Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame

December 31, 2024

By Kevin Glew

Canadian Baseball Network

When Roberto Clemente’s plane carrying relief supplies to Nicaragua crashed 52 years ago today, down with it went the hearts and spirits of the thousands Clemente managed to touch during his short life.

With his death, baseball lost a vibrant superstar. Teammates mourned a respected leader. A family tried to come to grips with the loss of a devoted husband, father and son. And the world was less a great humanitarian.

Like Americans and Latin Americans, Canadians were shocked and saddened by Clemente’s death. Montrealers were especially devastated. Clemente had forged a special bond with the city and its fans at the beginning of, and during, his professional baseball career. It’s a bond that has been rarely written about.

Today, when historians talk about baseball legends with connections to Canada early in their career, they often mention Babe Ruth who hit his first professional regular season home run in Toronto or the courageous Jackie Robinson who suited up for the International League’s Montreal Royals in 1946 before breaking Major League Baseball’s colour barrier.

Seldom do they allude to Clemente, a fearless Puerto Rican player who honed his skills in Montreal before becoming a major league superstar.

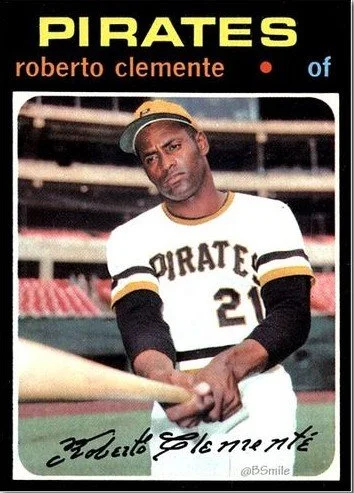

Remembered by most as a dynamic outfielder with the Pittsburgh Pirates, Roberto Clemente was a man whose on-the-field brilliance was matched only by his off-the-field generosity and humanitarian efforts.

And while today, on the 52nd anniversary of his death, Clemente will be mourned deeply in Latin America and the U.S., Canadians should also take some time to remember this selfless hero because before attaining baseball immortality, he spent his first professional season in Canada honing his skills and battling for playing time.

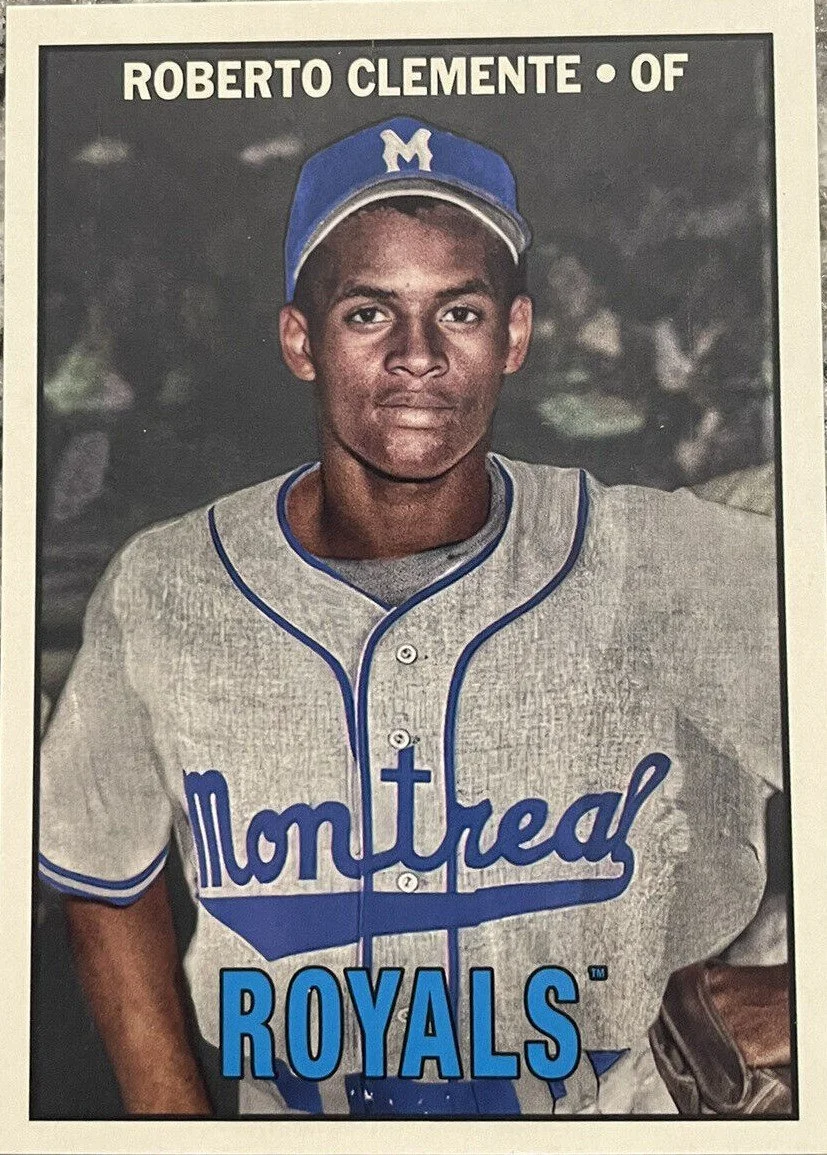

Scouted by Al Campanis and signed to a $15,000 contract by the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1954, Clemente was assigned to their International League affiliate Montreal Royals. With a rule in place that stipulated that any team signing a rookie to a contract over $4,000 must keep that player on their major league roster for the season or risk losing them in an off-season draft (equivalent to today’s Rule 5 draft), sending the talented youngster to Montreal was a gamble.

Clemente’s season with the Royals was a frustrating one for the raw and talented 19-year-old. Despite being one of the Dodgers’ best prospects, the slender outfielder was sent to the plate only 148 times in a 154-game season.

His lack of playing time was confounding for him. It was a trend that began after the Royals’ home opener, when after registering three hits in four at bats, he found himself on the bench for the next game. Even hitting a monstrous home run that cleared the left field wall and went right out of Delorimier Stadium (the first player to accomplish this) on July 25th of that season wasn’t enough to earn him a regular spot in the lineup.

So why did the Dodgers refuse to play one of their premier prospects on a consistent basis?

One of the reasons was practical. The Royals’ roster was chock full of outfielders, including future big league regulars Sandy Amoros and Gino Cimoli and minor league veterans Dick Whitman and Jack Cassini, so it was tough for Royals manager Max Macon to find playing time for Clemente.

But the most popular explanation for Clemente spending so much time on the bench is that they feared losing him in the off-season (Rule 5) draft and they didn’t want other teams to see how good he was.

“The evidence seems to indicate that the Dodgers were trying to hide him,” Bruce Markusen, author of “The Great One,” an excellent book about Clemente, told me in a 2002 interview. “I mean if you have a young player with that much talent and you’re trying to develop him, you don’t limit him to 148 at bats.”

In his book, Markusen also notes that during Clemente’s tenure with the Royals, the future Pirates star often took batting practice with the pitchers and would typically only play the second game of a doubleheader (most scouts from visiting teams would leave after the first game).

“[Royals manager Max] Macon had orders, and that was that,” Bob Watt, the Royals former road secretary is quoted as saying in David Maraniss’s outstanding 2006 Clemente biography. “Whenever we’d spot a scout in the stands, that would be the end of Clemente for that day. He never had a chance to show what he could do.”

Clemente is seated on the far left in the bottom row of this 1954 Montreal Royals team photo. Photo: Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame

Over the years, however, Macon and baseball historians like Stew Thornley have disputed the claim that Clemente was being hidden in Montreal. And Thornley makes a pretty strong case in this SABR article published in 2006.

“If you had been in Montreal that year, you wouldn’t have believed how ridiculous some pitchers made him look,” Macon once said of Clemente.

Macon insisted it was Clemente’s performance that inspired him to use the young outfielder so sparingly.

On-the-field frustrations aside, Clemente seemed to enjoy the city of Montreal, noted Markusen. He lived in a rooming house in the French half of town a few blocks from Delormier Stadium along with Cuban shortstop Chico Fernandez, who could translate for Clemente who spoke little English. Maraniss writes that the rooming house offered “beds but no meals” so Fernandez and Clemente ended up at the same breakfast restaurant every morning ordering ham and eggs. The city offered the Latin outfielder some refuge from the overt racism he encountered when he played in International League cities like Richmond, Va., but it was far from perfect. Maraniss writes of instances in Montreal where Clemente could recall being criticized for socializing with white women.

“From everything I’ve read, he was generally treated well in Montreal,” said Markusen in 2002. “I’ve read reports where he has said that the family (a white French family) he stayed with was very good to him.”

But the cultural solace Montreal provided was little consolation for the highly motivated Clemente. Driven to become a major league player, he grew disenchanted as the season wore on and considered going home to Puerto Rico.

Fortunately, his luck would change when Branch Rickey, general manager of the last-place Pittsburgh Pirates, dispatched scout Clyde Sukeforth to check out Royals pitcher Joe Black. Legend has it that the veteran scout grew so enamored with Clemente that he never did see Black pitch. The Pirates knew they would finish last in the National League that season and that would give them the first pick in the off-season (Rule 5) draft. And before the end of his trip, Sukeforth was convinced that the raw but athletic Clemente would be the first selection. The Pirates spoke with Clemente and told him as much and encouraged him to stick out his frustrating season in Montreal.

In fact, before Sukeforth left Montreal, he told Macon of the Pirates’ intentions to draft Clemente, according to a conversation shared in Maraniss’s book.

“Take care of our boy!” Sukeforth reportedly told Macon of Clemente.

“You’re kidding. You don’t want that kid,” Macon answered.

“Now, Max. I’ve known you for a good many years,” Sukeforth responded. “We’re a cinch to finish last and get first draft choice. Don’t let our boy get in trouble.”

And sure enough, when the draft day arrived, on November 22, 1954, the Pirates took Clemente with the first pick.

“It could be said that the course of Clemente’s career changed that year in Montreal,” said Markusen in 2002.

Claiming a starting position in the Pirates’ outfield in 1955, Clemente became a fixture in the team’s lineup for 18 seasons. In his career, he was selected to 15 All-Star games, won four batting titles and registered exactly 3,000 career hits. He was also a member of two World Championship-winning teams (1960, 1971).

While Clemente was proud of his baseball accomplishments, his humanitarian work off the field was equally important to him. In the off-season, Clemente would return to Puerto Rico to hold baseball camps for underprivileged children. And in 1971, he announced plans to build the Roberto Clemente Sports City, a facility that provides less fortunate children with instruction in different recreational activities that still operates in his hometown of Carolina today.

Clemente was also an outspoken leader for Latin players – using every opportunity he had to enlighten Major League Baseball and its fans about the racism and language barriers that Latin players had to overcome. Markusen writes that when Clemente started playing in 1955, there were only five other Puerto Rican players in the majors and 29 Latin players in total.

“He deserves a great deal of credit for the increase in the number of Latin players in the majors today,” said Markusen in 2002. “There has been a full generation since his passing and he is still very highly regarded in the Latin community.”

So, while Latin America and Clemente’s U.S. fans pay tribute to him today, on the 52nd anniversary of his death, Canadians should also pause and remember this brave baseball legend as well.

His stay in our country may have been brief, but his impact on and off the field will last forever.

In Canadian baseball history circles, Clemente may not be talked about as much as Ruth or Robinson, but his professional baseball career started here – in Montreal – and for our small part in shaping this magnificent man, we should be proud.

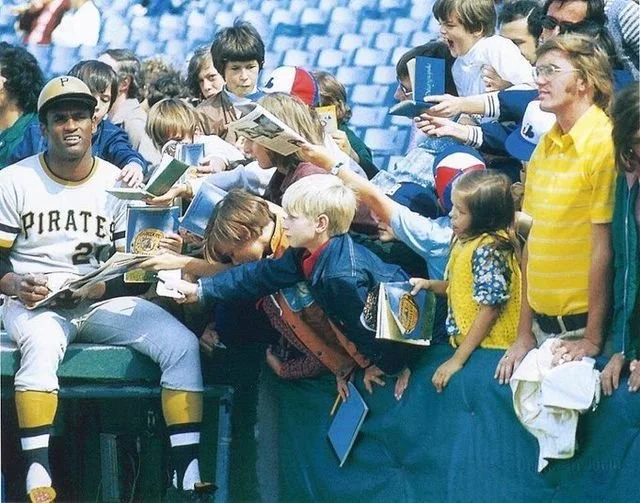

Roberto Clemente signs autographs for young fans at Montreal’s Jarry Park. Photo: Denis Brodeur

More Roberto Clemente Canadian links:

-As the above photo by Denis Brodeur illustrates, Clemente maintained a love for the city of Montreal throughout his playing career. He played 26 games at Jarry Park and batted .255 with 24 hits, including five doubles, two triples and a home run.

– Clemente’s first hit at Jarry Park came on July 14, 1969. In his first at bat at the stadium, Clemente singled off Expos right-hander Bill Stoneman in the second inning. Clemente notched an additional single and a double in that game to register his first of three, three-hit games at Jarry Park during his career. The Expos defeated the Pirates 2-0.

– Clemente’s first and only home run at Jarry Park was belted off right-hander John Strohmayer in the fifth inning of a Pirates’ 8-4 win over the Expos on May 23, 1970.

– The Pirates superstar’s final three-hit game at Jarry Park came in the Pirates’ 6-2, 13-inning win over the Expos on May 21, 1971. Two (single in the ninth and double in the 11th) of Clemente’s three hits came off of Canadian Baseball Hall of Famer Claude Raymond (St. Jean, Que.). Despite allowing the two hits to Clemente, Raymond pitched four scoreless innings in relief.

– Clemente’s final hit at Jarry Park was a single off Expos righty Mike Torrez on September 10, 1972. It was the 2,978th hit of his career. Torrez scattered eight hits that day in a complete-game, 8-2 victory for the Expos. It was Torrez’s 16th win of the season.

-Clemente belted his 240th and final major league home run off Canadian baseball legend Fergie Jenkins (Chatham, Ont.) at Wrigley Field on September 13, 1972. In total, Clemente went 26-for-95 off Jenkins, good for a .274 batting average. Clemente belted six home runs off Jenkins, but the Canuck right-hander also struck him out 14 times.