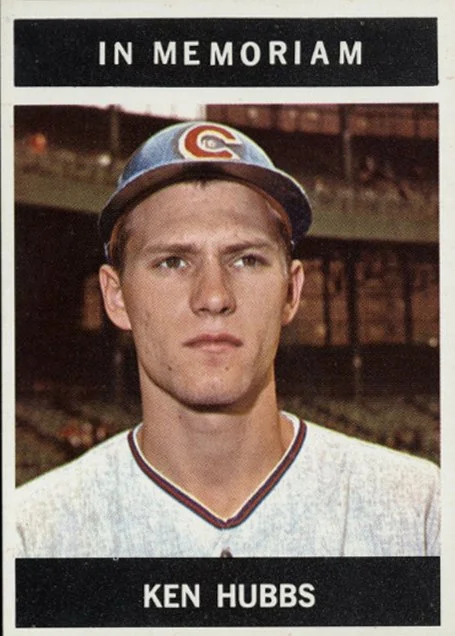

Mark Whicker: Gaudreau brothers tragedy brings to mind late Ken Hubbs of Cubs

The sadness over the loss of former Boston College stars, the Gaudreau brothers, would remind Cubs fans of the tragic death of former NL Rookie of the Year Ken Hubbs.

September 13, 2024

By Mark Whicker

Canadian Baseball Network

They give out the Ken Hubbs awards in San Bernardino, Ca.

The best high school players in the area are eligible. In 2019 Jayden Daniels, the quarterback from Cajon High, was the football winner. The actual award is probably deep in Daniels’ closet by now, since he won the Heisman Trophy and made the grand post-season banquet tour after he finished at LSU last year. Now a rookie with the Washington Commanders, there’s a chance Daniels hasn’t quite grasped who Ken Hubbs was.

He should, and all young athletes should, because Hubbs is a cautionary tale to this day. By the time he turned 22 Hubbs was a local legend and a national star, destined to camp out at second base in Wrigley Field for at least 15 years. But his life, like all our lives, was measured out in coffee spoons. Sixty years ago, he died when he tried to land a single-engine plane in a Utah snowstorm.

We think of Ken Hubbs because of what happened in south Jersey on Aug. 29. Johnny Gaudreau, a magician with stick and puck, was riding a bicycle alongside his brother Matthew who, like Johnny, played hockey at Boston College. They had just finished up the rehearsal for the wedding of their sister Katie, scheduled the next day. A car moved into the left lane of the two-lane road to give the Gaudreau’s room; a car behind it, driven by an alleged drunk, took the opportunity to accelerate and pass on the right.

That driver crashed into both bikes, and killed both Gaudreaus. Johnny’s wife Meredith was three months’ pregnant with their third child. Matthew’s wife was expecting, too.

Hockey players Matthew and Johnny Gaudreau were killed by a drunk driver on Aug. 29 when they were out riding their bikes the day before their sister’s wedding.

The sadness was only exceeded by the pointlessness. Gaudreau was an original on the ice, a little guy slaloming his way through traffic and beating goaltenders with either hand.

But it isn’t quite the same thing. Gaudreau was 31 and his career was well-established. Hubbs had played only two years in Chicago and had many years left to sky write his name. But the principle is the same. Athletes are supposed to play until they can’t, until their bodies give up the fight, until someone better comes along.

Few of them get to choose their exit ramp. But most of them at least get the chance to play their hand, to reach a conclusion they can understand. Gaudreau and Hubbs, and a few others over the years, were robbed of that chance, and so were their hordes of fans. It’s a special kind of grief, built in layers. Hubbs made his debut with the Cubs in September of 1961. He was a natural shortstop, but Ernie Banks owned that turf, so Hubbs spent uncountable hours learning a new position from coach Bobby Adams.

In 1962 the expansion Mets drafted second baseman Don Zimmer. Hubbs became the starter from the dawn of spring training and played 160 games. He won the National League Rookie of the Year Award, with 172 hits and a .260 average, but mainly because he set a major league record with 78 consecutive games and 418 chances without an error.

Chicago Cubs second baseman Ken Hubbs was the National League Rookie of the Year in 1962.

Phil Wrigley, the Cubs’ owner and chewing-gum magnate, tore up Hubbs’ contract halfway through the season and doubled his salary. Wrigley didn’t usually treat the hired help like that, but this was worth all the Doublemint he could sell.

Hubbs didn’t hit as well in 1963, fading to .235, but had another sensational year in the field, and the Cubs finished 82-80. He came back home, as always, and this time he took flying lessons, and on Feb. 12 he and his friend Denny Doyle boarded a Cessna 172 and flew to Provo, Utah.

Doyle’s wife Elaine had given birth to their first child, and she had ridden a train to Provo, where her parents lived. Hubbs and Doyle figured they’d fly in and surprise her. Plus, there was a charity basketball game that night. The next day Hubbs and Doyle would fly back to Colton, their hometown.

Elaine was at the airport the next morning when the plane lifted off. The weather, to the south, wasn’t good. Hubbs was an inexperienced pilot and had not filed a flight plan. He lost radio contact before long and tried to fly back to the Provo airport. At home, Ken’s dad Eulis, a polio victim, awaited word.

When the plane got over Utah Lake it fell victim to turbulence, and it crashed through 15 inches of ice. The fuselage was shattered, and rescuers needed grappling hooks to recover what was left of the bodies.

The memorial service for Hubbs featured a 20-minute procession of cars, and not enough seats for the mourners. The family asked for money to begin a foundation, in lieu of flowers, and that foundation remains today.

Although Hubbs was quiet and unassuming, he fit the template of what an early 60s athlete should be. He did not smoke, in an era when almost everyone did, and he convinced veteran third baseman Ron Santo that he should stop. He was a devout Mormon and a regular tither.

He took up a collection to help rebuild a Black school in Tennessee that was bombed. He became a priest in the church when he was 12 and sang in the choir. Hubbs was also the kind of mythic athlete that, unfortunately, gets channeled into one sport today. He played quarterback well enough to get notes from Notre Dame.

He played basketball well enough to get a visit from UCLA’s John Wooden. He would sometimes finish a baseball game, go to another field, and, still in his baseball uniform, win a high-jump competition. His parents put him in a boxing competition when he was eight, and the coaches quickly put him in the 12-year-old group.

He led Colton’s Little League to a runner-up finish at the Little World Series, where he hit a game-winning home run after he had broken his toe.

Ken Hubbs ... sounds a lot like Roy Hobbs, right? But Bernard Malamud wrote “The Natural,” the story of Hobbs and his bat Wonderboy, two years before Hubbs came to Williamsport.

The years have not totally extinguished the agony, and the agonizing questions. The young man who never made a misstep should never have flown that day, and probably needed more than 71 hours of flight time to do the trip in the first place. He was known to be terrified of flying. Sure, Hubbs had to overcome that to be a major league player.

That didn’t mean he had to learn to fly himself. Eulis told Keith, Ken’s brother, to talk him out of flying. He tried. Ken wound up talking Keith into flying instead.

“We were always trying to convert each other,” Ron Santo said. “I’m Catholic, he was a Mormon. But after he died, I had to see a priest. I couldn’t understand it. This was a kid who loved life. Why? Why him?”

It’s a question that never finds an answer. Just an echo.