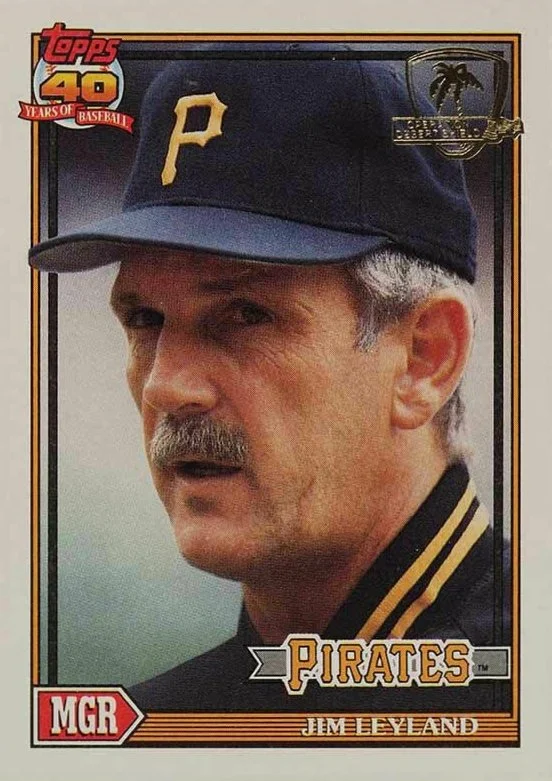

Mark Whicker: “Brazen and unconventional” Leyland has earned plaque in Cooperstown

Longtime big league manager Jim Leyland will be inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame on July 21 in Cooperstown.

July 11, 2024

By Mark Whicker

Canadian Baseball Network

Jim Leyland was like your first favourite car.

It started like a dream every morning. But all the miles were hard.

He managed 11 years in the minor leagues. His first stop was Bristol, in the Appalachian League. He was “stylin,’’’ as he recalled, with a new pair of white shoes that he unfortunately placed on the top of the hot water heater in the clubhouse.

Pretty soon they were bubbles.

“And I paid 40 bucks for those suckers, too,” Leyland said. He was 26.

He managed in Clinton and Evansville and Lakeland, never blessed with a ton of talent in the Detroit organization, but the way he did it left an impression on Tony La Russa, who was managing the White Sox’s triple-A team. When La Russa managed the White Sox, he hired Leyland as a coach. In 1986, Leyland got his first major league manager’s job, with a skeleton crew in Pittsburgh. He was 41 in real years, a lot older in baseball terms. That’s the way it was back then. You didn’t prove yourself in the video room. You handled young ballplayers who rode buses and stayed in Days Inns and played doubleheaders on 99-degree days and hailed from the Caribbean and the Great Plains alike. By the time your ship came in, you had pretty much seen everything.

Leyland will be inducted into the Hall of Fame on July 21, a manager with a pack of Marlboros on hand and every click of the odometer on his face. Rich Donnelly, a longtime coach, likened him to Gil Favor, the trail boss on the TV series “Rawhide.” Favor’s No. 2 man was a character named Rowdy Yates. Rowdy was played by Clint Eastwood. So Gil Favor, who was played by Eric Fleming in case you ever find yourself on Jeopardy Masters, had to be a pretty strong driver.

That was Leyland. Leadership is a skill, and Leyland’s ability to keep his foot on the gas and his feelings in check brought him a World Series title in Florida, two more World Series appearances in Detroit, and three consecutive N.L. East titles in Pittsburgh.

Leyland was the seventh manager to get to the Series with a team in both leagues, but he wasn’t much interested in numbers, and he isn’t remembered that way. He is remembered as the man at the head of the herd, cigarette dangling, with a faraway look in his eyes that missed nothing.

Many successful managers never knew success as a player. Leyland played seven minor league seasons and hit .219. Because of that, he knew the anxieties of the 25th men he would manage. Am I going down? Where am I playing next year? Do I have any chance of getting my pension? Leyland found ways to match those players up against vulnerable pitchers, managed to converse with them on most days, never forgot they were there.

In 1991, he used Roger Mason to get the last four outs of Game 5 of the N.L. Championship Series. Bill Landrum and Jim Gott were the closers. Mason was incredulous when he was allowed to bat in the ninth inning. But he got the job done, and the Pirates took a 3-2 lead in a series they would lose to Atlanta. Leyland could have cited the many shrewd reasons he did that, but he merely said, “Roger was the best guy in that situation, and I would have had to change too many things if I did something else.”

There were those who called Leyland brazen and unconventional. No one called him scared.

Leyland could handle the great ones, too. He had Barry Bonds and Bobby Bonilla in Pittsburgh. Bonds and his manager had a famous blowup in spring training, with Leyland yelling, “I’ve been kissing your ass for three years and I’m not doing it anymore,” but Bonds extolled Leyland and called him the “least racist manager” he’d ever played for.

One night Bonds had gone clubbing, and showed up the next day claiming he was too sick to play. He even lay on the couch in Leyland’s office.

“Now, you can’t go to the Hall of Fame if you don’t play all the games,” Leyland reminded him.

Finally he asked Bonds what the scene was like at that particular bar, and Bonds was shocked Leyland knew where he’d gone. The next night, Bonds was drooling over the chance to beat up on one of his favourite pitching victims, and Leyland benched him as a “precaution,” since he’d been too sick to play the night before. Bonds yelped and complained to general manager Syd Thrift, but Leyland stood his ground and made it known that if he couldn’t decide who played and who didn’t, maybe somebody else could drive this wagon train. It all passed, and Bonds won two MVP awards in three Pittsburgh years.

Detroit was Leyland’s home organization and was close to his hometown of Perrysburg, Ohio. Lakeland has been Detroit’s spring training headquarters since 1966. At the end of one spring training, someone asked Leyland if he was looking forward to the season.

“I sure am,” he said. “I’m Applebee’d out.”

And Florida was the place where Leyland won it all, although his star players were sold out from under him almost immediately. The same thing happened in Pittsburgh, yet Pittsburgh is the place that fit Leyland best, with a bunch of rumpled, underdog players supporting the stars, luring fans back to Three Rivers Stadium, with a manager who, for all you could tell, could have been a millwright.

Pittsburgh is where Leyland met his wife Katie, who delivered son Patrick on an off-day during a playoff series.

“That’s what a good baseball wife does,” Leyland said.

Pittsburgh is where he descended upon Gary Varsho, after Varsho had a rough time picking up pitches.

“Varsho, do you wear contacts?” Leyland roared. “Yeah? Well, put ‘em in next time!”

Nothing was sweeter than that first N.L. East pennant in 1990, when the Pirates flew home from St. Louis on a Sunday night, elevated in artificial ways as well. There was a party awaiting in Pittsburgh, and Leyland claimed to be so impaired that when he dropped a quarter in the parking lot and saw the pointer go up to 60 minutes, he gasped and said, “Damn, I’ve lost 100 pounds.”

But Pittsburgh, or games involving Pittsburgh, tried mightily to break his heart. In 1992, the Pirates led Game 7 in Atlanta by two runs in the ninth. It ended when Francisco Cabrera’s base hit scored Sid Bream, who had been the Pirates’ first baseman and a favourite of Leyland’s, until Bream found a better contract in Atlanta. The Pirates’ clubhouse was a morgue and the flight home was nearly silent, except for Bonds saying goodbye to his teammates, on the way to riches in San Francisco.

“It was like we were all carrying packages of C-4 and we were afraid the plane would blow up if we said anything,” said Andy Van Slyke.

Leyland did the best he could to comfort.

But mostly he was in the seat with the light on, trying to figure out the Pirates’ lineup for 1993.

The West Coast didn’t interest Leyland.

“You go to those Dodger games and all the fans have those puka-shell necklaces on,” he’d say.

On one Saturday, Los Angeles was collectively locking its doors as it awaited a second verdict in the Rodney King case.

Leyland was in his visiting manager’s office at Dodger Stadium. He claimed to know nothing of Rodney King.

“I’m more worried about Jeff King,” he said, referencing his third baseman.

It’s not easy for anybody to make the Hall these days, particularly managers, who have to wait for the Veterans Committee’s call. Davey Johnson, who finished 301 games over .500 and made almost every team he managed better, hasn’t gotten in.

Neither have Tom Kelly or Danny Murtaugh or Cito Gaston, with two World Series championships apiece. And don’t even ask about Billy Martin.

Do managers make a difference?

Well, the Cubs thought they’d bought the missing piece when they hired Craig Counsell away from Milwaukee, and now the Brewers are still atop the N.L. Central and the Cubs are up the track. It’s hard to remember how reluctant the Braves were to make Brian Snitker the fulltime boss, because Snitker’s 19 years in the minors had typecast him, but the past nine years in Atlanta have shown how ready he was.

Leyland’s journeys did the same for him. It’s easier to handle the miles when the last one takes you to Cooperstown. He’ll walk in next week, with shoes intact.