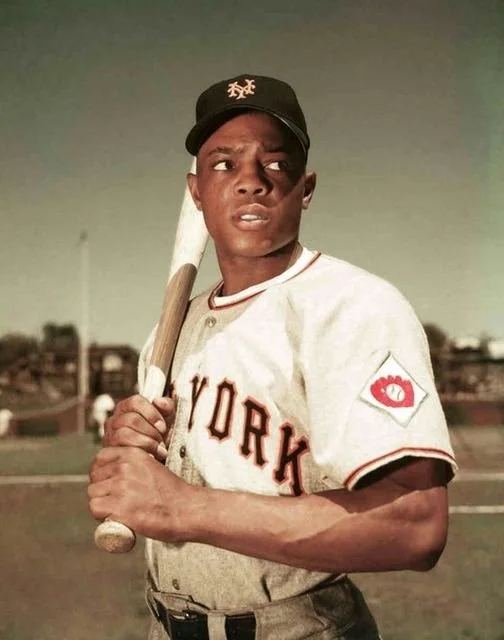

Mark Whicker: Numbers indicate finding “Next Willie Mays” will be difficult

Willie Mays passed away on June 18 at the age of 93.

June 28, 2024

By Mark Whicker

Canadian Baseball Network

For those of a certain age, the death of Willie Mays was a ride in the Wayback Machine.

America knew him through black-and-white film clips, since major league baseball was rarely televised nationally, and through the power of oral history. People were transfixed by the catch he made in the 1954 World Series, off Vic Wertz in the Polo Grounds. They were stunned, and thrilled, to learn that Mays thought other catches were better. Through such limited visibility, people came to think that Mays brought a bag of thrills every time he came to the ballpark.

He didn’t, of course. He had his 0-for-4s, just as Wayne Gretzky sometimes had his clean sheets. In that ‘54 season, when the Giants unexpectedly swept Cleveland in the World Series, they drew an average crowd of 15,198. That didn’t mean Willie wasn’t appreciated, or even idolized. It just meant that baseball, and all sports, didn’t take up as much space in our lives.

Among the amateur eulogists was a fellow on PBS NewsHour who said Mays would be particularly missed because we have no stars in modern baseball. This might come as a surprise in New York, where Aaron Judge has 30 home runs before the first of July. Or in Los Angeles, where Shohei Ohtani leads the National League in runs, batting average, slugging percentage and OPS. Or in Philadelphia, where nightly sellout crowds get quiet when Bryce Harper, the local gladiator, comes to bat.

Mays might well be the best player who ever lived. It’s difficult to argue that he isn’t. But it shouldn’t blind us to the feats of the astonishing athletes we have now, along with those of Barry Bonds, Ken Griffey Jr., Cal Ripken, Derek Jeter and the others who, in their own way, were inspired by a player they rarely saw.

Some players, particularly some Giants, were haunted by Mays. The first Next Willie Mays was Bobby Bonds. He actually played in the same outfield with Mays, and Mays made a famous catch while the two collided in Candlestick Park one day. Like Mays, Bonds mastered all of baseball’s skills but also fell victim to some of its challenges, mostly in the area of contact. A drinking problem also interfered. But Bonds was the second player to reach 300 home runs and 300 steals. Mays was the first, and Bonds had five 30-30 seasons.

The next Next Mays was Chili Davis. He hit 19 home runs as a Giants rookie in 1982. He would play 19 years and, like Bonds, wear a closetful of uniforms, and he wound up with an .811 OPS and 350 homers, and World Series rings with the Yankees and Twins. Fortunately, Davis was enough of a realist to separate everyone else’s dreams from his own. He knew there were no Next Mozarts or Oliviers or Mayses.

On June 20, two days after Mays died, the Giants and Cardinals played a game at Birmingham’s Rickwood Field on Thursday, commemorating the Negro Leagues. Rickwood was built in 1910, and Mays played there for the Birmingham Black Barons, as did Satchel Paige and Lyman Bostock Sr., whose son was a talented outfielder for the Twins and Angels. It’s a shame Mays couldn’t re-enter his old stomping ground, but he was 93, and it would have been a long trip and a very hot night.

There was still an outpouring for Mays that was an educational gift for those who don’t remember Willie, Mickey and The Duke, not even as a sappy Top 40 hit. He did things nobody else could and did them like no one else would.

But there was an extra dimension to the sadness. If there is a Next Mays he is playing quarterback for the Arizona Cardinals. Or maybe shooting guard for the Cleveland Cavaliers. Kyler Murray was the ninth choice in the 2018 baseball draft, and he drove in 48 runs in 51 games for Oklahoma. But he also won the Heisman Trophy and picked the NFL instead. Donovan Mitchell grew up around baseball because his dad was a minor league manager in the Mets’ organization. He didn’t pick the NBA until he broke his wrist in high school, and decided basketball was a lesser risk.

Jameis Winston was another Heisman winner who picked quarterbacking over baseball. He was the closer for Florida State. Charlie Ward also won the Heisman at FSU and was drafted twice in baseball, but knew he was suited for hoops and had a nice career for the Knicks.

According to the Society of Baseball Research, Black players made up 18.7 percent of MLB rosters in 1981. That was an all-time high. In 2024 they make up six percent.

Could you ever conceive of a day when there would be a higher percentage of Blacks in hockey than in baseball? Better get ready. At the moment, NHL rosters are 4.5 percent black. Reasons abound, most of them outside the purview of MLB, which has emptied its think tanks in trying to reverse the curve.

If there’s a leading culprit, it might be the proliferation of summer youth teams under the catch-all of Travel Ball. It is expensive, it is normally based in the relative whiteness of the suburbs, and it works to exclude Black athletes who are being asked to play AAU basketball in the summer, or attend football camps and practices.

Those who have an eye toward professional riches have no doubt noticed that NBA and NFL players get to the big money quicker than those in baseball, and those players don’t have to ride minor league buses and eat at Taco Bell drive-thrus. It really becomes an easy decision. Dave Winfield was drafted in all three sports and chose baseball. It’s doubtful he would do so today.

College baseball is also stuck at six percent Black participation. Maybe the chaos of college athletes will change scholarship limits across the board, or do away with them altogether, but at the moment college baseball works on an 11.7 scholarship limit. That’s for a lineup card that includes 10 players, including the DH. Football, which has 22 starters, enjoys 85 scholarships. Thus, few ballplayers get full scholarships. That also simplifies the options.

The style of major league baseball has also changed, and those changes have impeded Blacks. There is a need for pitchers, in the era of short starts. In the 60s and 70s, there were eight or nine pitchers on each team. Now there might be 13. More than half the players are pitchers and on many travel ball teams, Black players are channeled to the outfield as youths.

Competition from the Caribbean and the Gulf might be the most influential factor of all. In that 1981 season, only 11.1 percent of major league players were Latino. This year, it’s 29 percent. Of the top 20 batters in OPS at the moment, eight are from the Caribbean or South America.

The Black attrition is self-perpetuating. Mays, Hank Aaron, Frank Robinson and others actively counseled young players of colour (and others, if you recall the way Robinson and Vada Pinson helped guide Pete Rose). Ken Griffey Jr. gave a poignant interview to MLB Network the night Mays died, saying his heart “was on the floor” and remembering how he came to expect to hear from Mays regularly. When Griffey would make an error, Mays would squeakily ask if Griffey’s glove was working, and if he wanted one of Willie’s.

“It would be the wrong hand,” the lefthanded Griffey would reply.

“It was tough love,” Griffey said. “If I wasn’t going well he’d say, ‘Pick it up. You’re better than that.’ If I needed help he’d say, ‘Settle down. You’re young. You’re going to be all right.’ He was always someone who cared.”

Will Judge or Mookie Betts show the same empathy? Or will anybody be there to listen?